Every American knows what the CIA is. I would guess that maybe 1 in 1,000 have ever heard of INR — the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, American diplomats’ in-house intelligence agency.

May 28, 2024:

Every American knows what the CIA is. I would guess that maybe 1 in 1,000 have ever heard of INR — the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, American diplomats’ in-house intelligence agency.

But if you do know about INR, you probably know two things:

INR is the Cassandra of American intelligence, and it earned that reputation the hard way.

As early as 1961, INR analysts were warning that South Vietnam’s battle against the North and the Viet Cong insurgency was failing, and would ultimately fail because the Viet Cong had the support of villagers in the South. Their analyses prompted furious rebukes from the likes of then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. But they were right.

In 2002, it happened again. The CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and the rest of the intelligence community had concluded that Iraq’s Saddam Hussein was trying to build nuclear weapons, which became one of the ostensible motivations for the US invasion. INR thought their evidence was nonsense. It was right.

In 2022, it happened again. The intelligence community predicted that Russia would win its war on Ukraine easily, cruising into Kyiv in a matter of days. INR dissented, arguing that Ukraine would put up a spirited fight and prevent Russia from getting anywhere near the capital. It was right. (Brett Holmgren, INR’s current chief, took pains to tell me that INR was not the only dissenter but confirmed that the bureau thought Ukraine would put up a strong fight.)

“You can get other intel agencies really upset about this when you point this out,” says Ellen McCarthy, who led the bureau from 2019 to 2021 after many years in other parts of the intelligence community. “But I’ve got to tell you, INR is almost always right.”

The bureau’s stellar track record seems, on paper, inexplicable. INR is tiny, with fewer than 500 employees total. The DIA has over 16,500, and while the CIA’s headcount is classified, it was 21,575 in 2013, when Edward Snowden leaked it.

You could fit over 47 INRs in the CIA, and even if you exclude the non-analysts on the CIA’s payroll, Langley’s analytic headcount is far greater than INR’s. Tom Fingar, who led the bureau from 2000 to 2001 and 2004 to 2005, once told a reporter its budget was “decimal dust.” In 2023, it came to only $83.5 million, or 0.1 percent of overall US intelligence spending.

On top of that, INR has no spies abroad, no satellites in the sky, no bugs on any laptops. But it reads the same raw intel as everyone else, and in at least a few cases, was the only agency to get some key questions right.

Saying “INR does a better job than DIA or CIA,” as a general matter, would go too far, not least because making a judgment like that in a responsible way would require access to classified information that the press and public can’t read. But it clearly is doing something different, which in a few key cases has paid off. And at least some policymakers have noticed. Bill Clinton told the 9/11 Commission he found memos by INR more helpful than the President’s Daily Brief, then prepared by the CIA.

I spoke to 10 veterans of the bureau, including six former assistant secretaries who led it. While no single ingredient seems to explain its relative success, a few ingredients together might:

Intelligence analysis is a notoriously difficult craft. Practitioners have to make predictions and assessments with limited information, under huge time pressure, on issues where the stakes involve millions of lives and the fates of nations. If this small bureau tucked in the State Department’s Foggy Bottom headquarters has figured out some tricks for doing it better, those insights may not just matter for intelligence, but for any job that requires making hard decisions under uncertainty.

INR began life as the research and analysis (R&A) section of the Office of Strategic Services, the US’s World War II-era spy agency. When its parent office was dissolved after the war, the R&A section was given to the State Department.

It was not an easy marriage at first. “They were distrusted by the [State] Department’s regulars who considered the newcomers too liberal in their views and unable to offer anything that could not be provided through traditional diplomatic methods,” historian Lawrence Freedman wrote in 1977. The division was then disbanded in 1946, before being reconstituted in 1947 as the bureau that still exists today. INR vets note with pride that its founding predates that of the CIA.

“The unit is handicapped by its small size,” Freedman noted of INR, “and has only made an impact through the quality of its personnel.” Indeed, early in the Vietnam war there was only one analyst at INR for North Vietnam and another analyst for the South; by 1968, at the war’s apex, that grew to four South Vietnam and two North Vietnam analysts. Six people, for a war that was tearing a whole region and, increasingly, American society itself, apart.

Luckily, the quality of that personnel was very high. The key analyst on North Vietnam was a woman named Dorothy Avery, a former CIA analyst who had a master’s degree in Far Eastern Studies from Harvard University. Fingar, the former INR chief, overlapped with Avery at the bureau when she was a senior presence, and he a very junior one. “We joked about Dottie Avery — she didn’t like it — but that Dottie Avery started doing Vietnam when Ho Chi Minh wore short pants,” he recalls.

Almost as soon as Avery arrived at INR in 1962, she and her supervisor Allen Whiting proved their mettle by predicting that China and India would engage in border clashes, then pause, then resume hostilities, then halt. All of that happened.

But INR also had messages that the Kennedy and Johnson administrations of the time didn’t want to hear. In 1963, the bureau prepared a report of statistics on the war effort: the number of Viet Cong attacks and the number of prisoners, weapons, and defectors collected by the South. All of the trendlines were negative. The report prompted a furious protest from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who argued that the South Vietnamese were succeeding. Defense Secretary McNamara echoed their protest.

But INR stayed pessimistic, and because of that, stayed accurate. Avery pushed back on the military’s assessment that “the application of force would induce Hanoi to make concessions,” arguing instead that “Hanoi felt it was on a roll and held the advantage in South Vietnam,” historian John Prados writes. That led her and INR to “predict accurately that North Vietnam would up the ante in the South, increase its support to the NLF [the National Liberation Front, the political arm of the Viet Cong] and perhaps send its own troops to fight.”

The bureau accurately predicted that in 1965, China would send thousands of troops to North Vietnam to support its ally; they insisted that bombing could not break North Vietnamese supply lines, and were right about that too.

In 1969, after over 30,000 American troops had died — along with hundreds of thousands, if not more, Vietnamese soldiers and civilians had died — INR commissioned an internal review by Avery and two colleagues documenting, in clinical detail, that they had seen this all coming.

Decades later, as the US began preparations for the Iraq war, INR would see arguably its finest moment. Its leader was Carl Ford, a veteran of the CIA and DIA who hadn’t previously served at INR. But he was fiercely loyal to his team, and his team had an unusual perspective on Saddam Hussein and nuclear weapons.

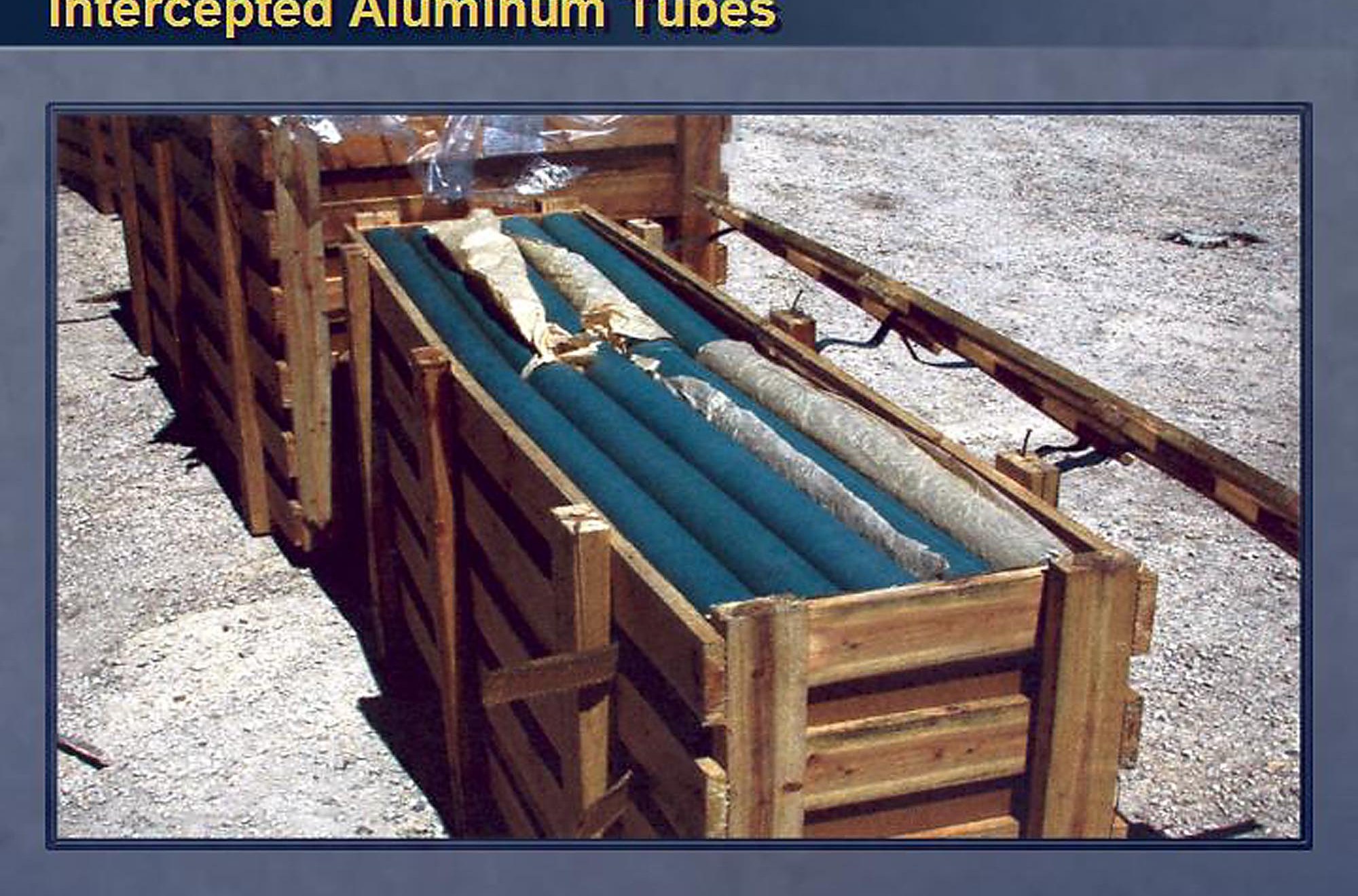

The evidence that Hussein was reconstituting Iraq’s nuclear program — a contention that fueled Bush administration officials’ arguments for war, like national security adviser Condoleezza Rice’s famous quip, “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud” — had two primary components. One was a finding that the Iraqi military had been purchasing a number of high-strength aluminum tubes, which the CIA and DIA thought could be used to build centrifuges for enriching uranium.

On September 6, 2001, five days before the 9/11 attacks, INR issued a report disagreeing with that finding. For one thing, scientists at the Department of Energy had looked into the matter and found that Iraq had already disclosed in the past that it used aluminum tubes of the same specifications to manufacture artillery rockets, going back over a decade. Moreover, the new tubes were to be “anodized,” a treatment that renders them much less usable for centrifuges.

“You can make a centrifuge out of these things, but no one in his right mind would,” as Ford explained to me.

The other major evidence offered for the claim that Iraq was pursuing nukes was an allegation that they had tried to buy “yellowcake” uranium from Niger; this is a partially processed form of mined uranium that could in theory be processed further and used for a bomb. When the claim first emerged in late 2001, INR was immediately skeptical, per an ensuing Senate investigation.

INR found the claim “highly suspect” because French businesses controlled the Nigerien uranium sector, and the French government was unlikely to actively assist Iraq in getting uranium. As more information came in, the CIA and DIA “were more impressed,” while INR “continued to doubt the accuracy of the reporting” given that Iraq was “bound to be caught” if it followed through.

About a year later, an Italian journalist leaked to the US Embassy in Rome a purported Nigerien government document detailing the purchase. Fingar showed the document to an INR analyst who had served as a foreign service officer in Niger. “He looked at the putative document and he says, ‘That’s a forgery. It’s an obvious forgery,’” Fingar says. “How do you know it’s an obvious forgery? ‘In Niger, when they sign, the line is on a diagonal. This is horizontal. It’s obviously not an official document.’”

In 2004, a Senate committee reviewing the colossal intelligence failure behind the Iraq war concluded that “only INR disagreed with the assessment that Iraq had begun reconstituting its nuclear program.” It was perhaps the biggest success in the bureau’s history, and it managed to become publicly known, winning the bureau glowing profiles from the Washington Monthly’s Justin Rood and the Washington Post’s David Ignatius.

For their part, INR veterans tend to be less triumphalist, preferring to say they were merely “less wrong” than other agencies. They agreed with other agencies that Iraq still had biological and chemical weapons, and they got that wrong.

And INR’s broader track record is far from spotless. To name one since-declassified example, a 1977 report on Iran predicting “the prospects are good that Iran will have relatively clear sailing until at least the mid-1980s” has not aged well, coming just two years before the Shah was deposed in a mass popular uprising and three years before the beginning of the devastating Iran-Iraq war. INR also got egg on its face in 2009 when longtime analyst Kendall Myers was revealed to have been spying for Cuba for decades (though INR was far from the only agency penetrated by spies).

But the successes appear to outweigh the misses. Even on Iran, INR was earlier than the CIA or DIA in warning amid 1978’s protests that there was a real chance the Shah would be forced out. In May 1973, INR analyst Roger Merrick argued that there was a “better than even bet” that Egypt would start a war with Israel “by autumn.” Egypt launched the Yom Kippur War in October.

Rood noted in 2000 and 2001, the CIA thought North Korea would soon test an intercontinental ballistic missile. INR doubted they’d get there in the next decade. As it happens, the first North Korea ICBM test was in 2017, sixteen years later.

Philip Goldberg, who ran INR from 2010 and 2013 and now serves as US ambassador to South Korea, recalls the bureau’s terrorism section being able to tell him, in real time, the ideological motivation behind the 2011 Norway massacres and the perpetrators of the 2012 attack on a US compound in Benghazi. In the former case, there was widespread speculation that al-Qaeda was responsible — but the INR team correctly identified it as a neo-Nazi attack.

Fingar told me yet another favorite win. “The specific issue was, would Argentina send troops to the multinational force in Haiti?” in 1994, as the US assembled a coalition of nations, under the banner of the UN, to invade and restore Haiti’s democratically elected president to office. “Our embassy had reported they’d be there. Argentine embassy in Washington: they’ll be there. The State Department, the Argentine desk: they’ll be there. [The CIA]: they’ll be there.” But, “INR said, no, they won’t.” The undersecretary running the meeting, Peter Tarnoff, asked which analyst at INR believed this. He was told it was Jim Buchanan.

At that point, as Fingar remembers it, Tarnoff ended the meeting, because Buchanan’s opinion settled the matter. That’s how good Buchanan’s, and INR’s, reputation was. And sure enough, Argentina backed out on its promise to send troops.

INR veterans describe their bureau in glowing terms, and some outsiders tend to agree. In one essay, the veteran CIA analyst John A. Gentry went so far as to recommend as a reform measure for the rest of the intelligence community to “model strategic, all-source analysts after the stereotypical INR analyst.”

But the agency’s reputation as contrarian sticks out too. “Gadflies of the intelligence community” is how Stephen Coulthart, a professor at the University at Albany and one of the few academics to study INR, puts it. “We had this reputation of being kind of … I guess they called this the red-haired stepchild. Being kind of snitty,” recalls Bowman Miller, former Europe chief at INR.

They’re informal; one alum told me you’d “put your coat and tie on” if you had to meet with the Secretary of State, but not otherwise. They’re the only intelligence agency that does not require polygraph tests — which private sector employers are banned from using for the simple reason that they do not work at all — in hiring.

Rod Schoonover, who worked in the bureau analyzing climate change and related issues from 2009 to 2019, told me about a commemorative “challenge coin” made for INR that he received. It depicts a tiny numeral 1 in superscript above the R, designating a footnote.

In intelligence argot, “footnote” has another meaning: It means a dissent or a major disagreement with a broader assessment made by colleagues. INR dissented so much that it threw a joke about it onto its coin. “They’re proud of dissent and particularly proud of dissent when they get it right,” he recalls.

The most important factor in building this culture, every veteran I spoke to stated, is the unusual way that INR selects and uses analysts. The CIA and DIA tend to favor generalists. Analysts rotate between roles every two to three years, often changing countries or even regions. At INR, the average analyst has been on their topic for over 14 years. “At most of the other intel organizations you rotate out of your portfolio every two to three years,” McCarthy says. “At INR, they die at their desks.”

INR, like the rest of the State Department, employs many foreign service officers, who do rotate between roles every three years. That helps the bureau stay current on particular countries’ cultures, enabling victories like their Niger analyst recognizing the yellowcake documents as a forgery. A past FSO working as a Russia analyst, John Evans, came to the role after a job at the US consulate in St. Petersburg in the 1990s, where he talked regularly with the office of mayor Anatoly Sobchak. His contact was Sobchak’s deputy, Vladimir Putin. Once Putin moved into a somewhat bigger job, that background came in handy.

Sixty-nine percent of INR employees are in the civil service, not the foreign service. That means no rotation. They are hired specifically for INR, and are meant to stay there for a long time. Many of them are recruited from academia. Miller came after earning his doctorate in Germanic languages and literatures at Georgetown. Tom Fingar was a political scientist at Stanford researching China when he joined. Schoonover was a tenured professor of chemistry at Cal Poly.

McCarthy notes that INR analysts tended to earn less than their CIA analogues, but Fingar argues that retention was no problem. “I asked my admin people, why do people leave? What’s the number one reason people leave? Retirement. Number two, death.”

Once hired, analysts enjoyed a quite flat organization. There weren’t many layers of hierarchy, and even managers made time to work on their own analyses. That could sort out some particularly ambitious people; Mark Stout, a former analyst, says he left for the CIA in part because there was little room for promotion and advancement within INR. It was a somewhat more staid place, whereas the CIA felt more fast-paced and dynamic. “The problem with [INR] bureaucratically is people don’t get promoted,” Miller says. Daniel Bennett Smith, who led the bureau from 2014 to 2018, told me he fought to create a new senior analyst role that would be paid at GS-15 scale (minimum $164,000 a year) rather than GS-13 (minimum $118,000), so longtimers had some means of promotion.

But the flat structure, combined with the agency’s tiny size, means analysts get a great deal of freedom. Vic Raphael, who retired in 2022 as INR’s deputy in charge of analysis, notes that analysts’ work “would only go through three or four layers before we released it. The analyst, his peers, the office director, the analytic review staff, I’d look at it, and boom it went.” Very little separates a rank-and-file analyst from their ultimate consumer, whether that’s an assistant secretary or even the secretary of state.

By contrast, CIA and DIA analysts have to deal not only with more hierarchy above them, but a greater number of fellow analysts working on their topic. They have to coordinate with their fellow analysts before moving forward. At INR, however, most countries have only one analyst assigned to them, and that analyst probably has other countries in their portfolio too. As a result, that analyst gets a lot of influence.

This helps explain why INR has sometimes been able to stake out positions at odds with the rest of the intelligence community: its writing process emphasizes individuality rather than groupthink.

The bureau also stands out as unusually embedded with policymakers. Analysts at other agencies aren’t working side by side with diplomats actually implementing foreign policy; INR analysts are in the same building as their colleagues in State Department bureaus managing policy toward specific countries, or on nonproliferation or drug trafficking, or on human rights and democracy. Goldberg, who led INR under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, notes that “we could respond much more quickly than farming it out to another part of the intelligence community, because on a day-to-day basis, we had an idea of what was on her mind.”

INR has another key tool in its kit: polling. Its Office of Opinion Research (INR/OPN) conducts public polls of populations around the world to gauge public sentiment. Raphael notes that Pew Research Center has recruited from OPN because “it’s like Pew on steroids.”

INR’s successful call on the 2022 Ukraine invasion reportedly came because OPN’s polling found that residents of eastern Ukraine were more anti-Russian and more eager to fight an invasion than previously suspected. The polling, Assistant Secretary Brett Holmgren says, has “allowed us to observe consistently, quarter over quarter, overwhelming Ukrainian will to fight across the board and willingness to continue to defend their territory and to take up arms against Russian aggression.”

INR alums are incredibly proud of their history, of their record of dissent and vindication on Vietnam, Iraq, and so much more.

But the bureau is also evolving. When McCarthy came in as assistant secretary in 2019, she recalls that the group had fallen behind on IT. “There was this thing called the internet,” she said. “And INR was not necessarily a big user of it.”

INR had also shrunk to a size where, as much as its nimbleness could be an asset, it was struggling “to keep up with requirements,” as McCarthy put it. She pushed to grow the bureau, and its staff of federal employees (excluding contractors) rose from 315 to 336 between 2019 and 2020.

“We were so used to getting onesies and twosies each year,” Raphael recalls, referring to hiring one or two more analysts. “With her we got maybe up to 10, and for us that was like, holy cow!”

Holmgren, who has led the bureau under President Biden and Secretary Antony Blinken, has invested heavily in IT improvements, and created a new product called the “Secretary’s Intelligence Brief,” modeled on the President’s Daily Brief but more targeted for what Blinken, or any future Secretary, needs to know. His vision is for the bureau to serve an analogous role for diplomats to that served by military intelligence for soldiers, a “diplomatic support agency” providing granular knowledge that ambassadors and foreign service officers need.

But he also wants the bureau to retain the spirit it’s had since 1947. “There’s a handwritten note that is framed in INR’s front office, from Secretary [Madeleine] Albright,” he says. “She wrote it on January 20th of 2001, her last day as secretary of state. I want to read you the quote because it’s something that’s resonated with me since I joined INR. It says, ‘This is my last summary from INR. And I cannot imagine how I will have any idea about what is really going on without you.’”