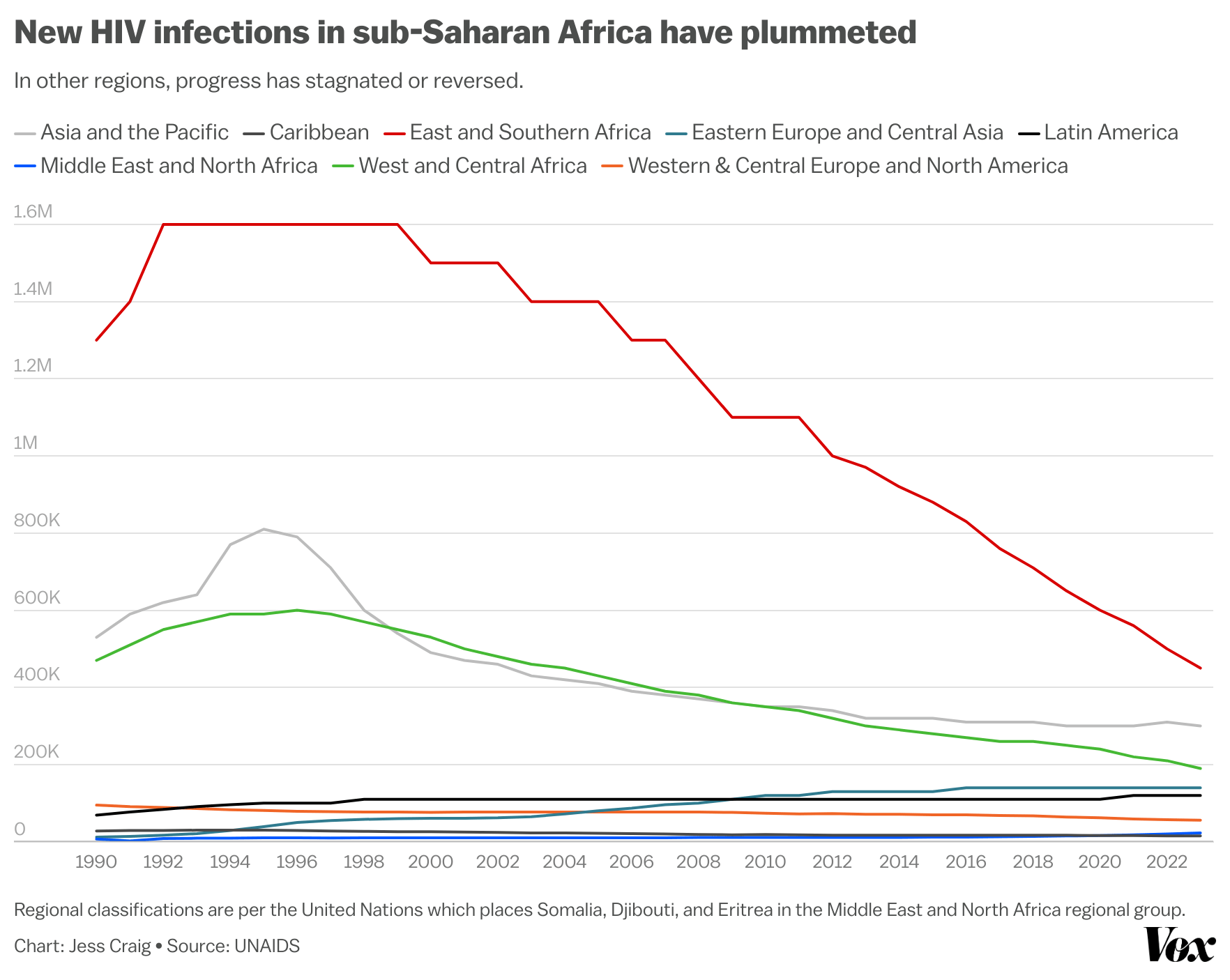

More than a million people were newly infected with HIV last year, adding to the nearly 40 million people currently living with the disease. But for the first time since 1981, when the disease first emerged, the majority of new HIV infections occurred outside of sub-Saharan Africa.

That’s a major milestone. The region — which includes 49 countries in southern, western, central, and eastern Africa — still bears the brunt of the epidemic. In 2023, 64 percent of people living with HIV were in sub-Saharan Africa, and about 62 percent of all AIDS-related deaths from the disease occurred there. But in the past few decades, there has been tremendous progress. The number of people in sub-Saharan Africa becoming newly infected with HIV has plummeted from 2.1 million in 1993 to 640,000 within 30 years — a 70 percent drop.

But as the number of new infections in the region declines, progress in the rest of the world has been stalling, or even reversing, according to a recent report from UNAIDS, the United Nations’ dedicated HIV and AIDS program.

New HIV infections in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East/North Africa have been increasing over the last two decades, due to a variety of factors including a lack of access to HIV testing and treatment, displacement and migration, and an uptick in the number of people using intravenous drugs. Before 2009, less than 10 percent of all new HIV infections occurred across those regions — but last year, that number rose to just over 20 percent.

It’s good news that sub-Saharan Africa, the region historically most affected by HIV, has dramatically reduced the number of people newly infected with HIV. The fight against HIV, however, is far from over. Growing funding gaps and the possible partial closure of the US government’s most important HIV program threaten to stall progress.

But the success in Africa has demonstrated that sustained efforts can dramatically reduce the HIV burden and are worth investing in.

Why has sub-Saharan Africa been so successful?

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa have made huge gains in improving awareness of HIV and increasing access to HIV testing and treatment.

In 2023, about 80 percent of people living with HIV there had access to antiretroviral therapy, the highest rate of any region in the world. Antiretroviral therapy, a combination of drugs that treat but do not cure HIV, prevents the virus from replicating. After about six months of typically daily treatment, the amount of the virus in most patient’s bodies is so low that they can no longer infect others. But just a few months or even a few days of missed therapy is enough to allow HIV to start replicating again.

Antiretroviral therapy is critical for reducing the spread of HIV. And because of such high treatment rates, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of HIV-positive people who are no longer infectious at around 74 percent. (The report classifies Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea as part of the Middle East and North Africa.)

A major focus of HIV programming in past decades has been testing pregnant women and then ensuring that HIV-positive pregnant women receive treatment throughout their pregnancy. This prevents mothers from passing the virus on to their babies. In 2010, just over half of HIV-positive pregnant women in eastern and southern Africa were receiving HIV treatment, but by 2023, that rose to an estimated 94 percent.

National governments in sub-Saharan Africa have also made it a priority to build out local capacity to fight the disease. The majority of funding for HIV services now comes from domestic sources rather than foreign donors. Rather than relying on foreign researchers and international groups to implement HIV interventions, local organizations — which are more integrated into the communities they serve and are more attuned to local social and cultural challenges — are increasingly running the show. In 2023, local organizations received 59 percent of HIV funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID), a 72 percent increase since 2018, according to the agency.

Girls and women, gay men, and sex workers are disproportionately impacted by HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and globally. Sexual intercourse is one of the key ways that HIV is spread. Gender-based violence and gender-based power disparities can expose such populations to the disease. Notably, in sub-Saharan Africa, 62 percent of new HIV infections in 2023 were among girls and women, whereas the majority of new HIV infections in the rest of the world is among males.

In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, social stigma, criminalization, underdiagnosis, and a lack of funding are driving an increase in HIV cases. Ukraine has long been an anomaly in Europe, with much higher HIV infection rates than most other countries in the region. Most HIV services have been restored since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, but there is ongoing fear that the conflict may further delay major progress in the country.

The main driver of HIV progress, of course, is sustained investment.

In sub-Saharan Africa, funding from international donors and local governments has contributed to the progress there. The region will need a steady, consistent flow to help sustain and build on achievements in reducing the HIV burden. Well-invested money can also alleviate some of the backsliding in progress in other regions, by ramping up HIV prevention and response activities.

But global funding for ending HIV is drying up. Between 2022 and 2023, global funding for HIV in low- and middle-income countries dropped 5 percent, or about $1 billion.

Even as the gap between need and funding grows, the US Congress is mulling the end of one of the world’s largest HIV programs: the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, commonly known as PEPFAR. Since 2003, PEPFAR has provided over $100 billion total in aid to provide HIV treatment to millions of people and to bolster response and prevention activities, the majority of which goes to African countries. Last year, PEPFAR funds represented about a quarter of total HIV funding in low- and middle-income countries from Haiti to Kenya to the Philippines.

PEPFAR is widely considered to be one of the most successful global health programs in the world, but some US legislators have soured on the program because of its inherent ties to sexual and reproductive health. HIV programming around the world has focused on improving safe-sex knowledge and practices. The sticking point for some conservative legislators is that some of the organizations that receive PEPFAR funds also provide abortion services.

In the wake of this dispute, the House Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies introduced a bill last year that would have eliminated nearly $500 million in HIV funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and over $3 billion in funding for the National Institutes for Health. Moreover, parts of the PEPFAR legislation are subject to congressional reauthorization.

PEPFAR has been reauthorized three times, for a period of five years each time. But last year after PEPFAR partially expired, members of Congress debated whether to renew it.

After a prolonged standoff, largely along party lines, the omnibus funding bill passed in March 2024 reauthorizing the program, but only for one year. Come next March, debates around PEPFAR will resume. Sub-Saharan Africa has achieved amazing progress but if the program is not extended, there will be a huge hole in the global HIV response. Millions of lives may be threatened.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here!