In 1974, after two years of “knocking on doors” and reporting the facts, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein published their debut book, All the President’s Men, condensing the Watergate scandal into something more gripping and galvanizing than any of their articles could manage: a thriller.

And theirs was a hit. All the President’s Men brought chaos to the White House and ruin to President Richard Nixon, who resigned eight weeks later; to its young authors, what was “perhaps the most influential piece of journalism in history” (Time) brought fame. Woodward and Bernstein were paid a $55,000 advance for All the President’s Men, and then a record-breaking $1.55 million deal for paperback rights to the sequel (about $10 million, in 2024 dollars).

That sequel, The Final Days, came out two years later but didn’t have that same air of revelation. Just Nixon handing the keys over to Vice President Gerald Ford; unsettling silent staffers with threats of suicide; getting drunk and roaming the White House, looking for Henry Kissinger. “Henry,” says Nixon at one point, falling to his knees, “we need to pray.” It wasn’t nearly as successful as its predecessor.

Woodward and Bernstein didn’t invent journalistic White House tell-alls — the now-routine book-length investigation of an ongoing presidency — but they did add a flash of glamour and intrigue to a genre that, then as now, has never been very popular. Profitable? Sure; but only briefly, until the scoops get swept up in the news cycle.

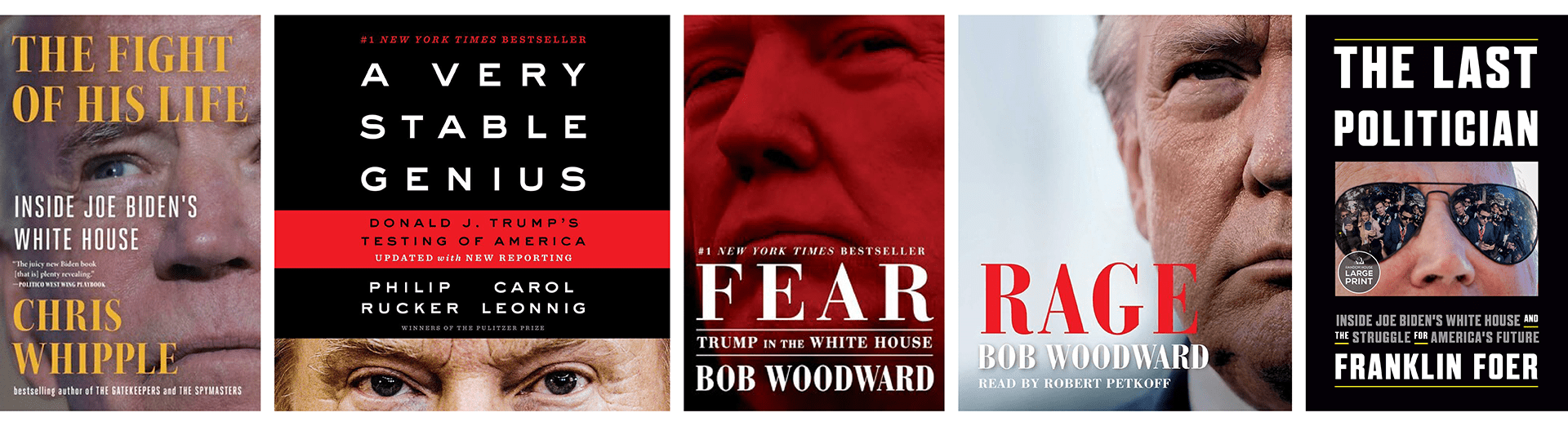

And yet the tradition endures, with Woodward — a figurehead in the field — forging ahead solo with exposés about George H.W. Bush in 1991, followed by two books about the Clinton administration, four about Bush Jr.’s, two about Obama’s, and four on Trump’s. But even these grand displays by the master of the form, so dignified and thorough, are largely forgotten after a quick burst of sales and scandal and TV appearances. Still, they come out in droves: Jonathan Karl gives us one trilogy (Front Row at the Trump Show, Betrayal, Tired of Winning), Michael Wolff gave us another (Fire and Fury, Siege, Landslide), Woodward a third (Fear, Rage, Peril).

The Trump era saw a mini-boom of these titles. There was Rick Reilly’s Commander in Cheat, Maggie Haberman’s Confidence Man, Bill O’Reilly’s United States of Trump — billed as “a rare insider’s look at the life of Donald Trump.” Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker gave us both A Very Stable Genius and I Alone Can Fix It.

Notably, these are distinct from the memoirs, which tell the life story of someone whose claim to fame was a few interactions with the president (Think: James Comey’s A Higher Loyalty, Bill Barr’s One Damn Thing After Another, or the two books Anthony Scaramucci got out of his week-and-change as White House director of communications).

There have been markedly fewer of these titles under Biden — but not none, and the trend continues. Publishers stand to earn fortunes, and authors to gain career-making exposure, but the risks are just as steep. For all the money Michael Wolff made with Fire and Fury, his blockbuster tell-all about then-President Trump’s first year in office, check out the stammering tension he exudes when grilled about suggesting, “between the lines,” that Trump was sleeping with then-Ambassador to the United Nations (and future campaign opponent) Nikki Haley. Consider, by extension, the precipitous drop in his next two volumes’ popularity.

Writing a book-length critique about the shortcomings of White House executives (i.e., extremely type-A careerist obsessives) is a laborious way to make enemies. So why do authors and publishers take the risk?

The math of journalistic tell-alls

For John Cavalier, owner of Cavalier House and Beausoleil bookstores in Louisiana, the White House tell-all is in the same league as politician memoirs and the news-pundit screeds: He tries to ignore them all. “[Whoever’s] on top of the polls this week might have a scandal next week … It’s just so hard to figure out the math of it … I’ve been a bookseller since 2003, and it used to be Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly books. They’d sell real good for two weeks, then a few months later they’re traded in.” And at that point “it’s pretty much over with.” The books go on the dollar cart. Clearance.

“They’re prestige projects,” says Andrew R. Albanese, executive editor at Publishers Weekly, “calling cards. The hope is, if [the publisher] can establish some kind of [political] audience, they’ll get ‘the big one,’” something like the President Barack Obama memoir. “They’re establishing credentials.”

“They’re prestige projects”

He describes it as a front-loaded market, meaning that a typical White House tell-all, if it’s good, will come out to a quick spike in sales, often it’ll make the New York Times bestseller list, enjoying maybe two weeks of coverage — and then it’s a hard plunge into discount piles, thrift stores, obscurity.

It’s an arc that Mitchell Kaplan, owner of Books & Books and co-founder of the Miami Book Fair International, has observed over his four decades as a bookseller. The books that are “embargoed before they come out … there’s a big expectation of revelation. [Customers] come, they buy it in a couple weeks, but then it’s all over the news. People feel they got it.”

Kaplan agrees these titles have been front-loaded for 40 years, but reader interest is getting harder to hold.

“Sometimes, in the past,” Kaplan explains, “[publishers] would maybe give first-review rights for a certain outlet. What’s happening now is that information is so diffuse, there isn’t one media outlet that can drive a book anymore. Used to be, if you had the cover of The New York Times Book Review, that drove it. But there has to be a longer promotional arc leading up to publication now.”

If a 24-hour news cycle doesn’t roll a title out of competition, there’s a risk of world events changing the narrative. Historian and political analyst Jonathan Alter — whose books The Promise (2010) and The Center Holds (2013) were among the first about Barack Obama’s presidency — feels mostly confident that what he was seeing and hearing while writing those books against urgent deadlines has been confirmed by history to be accurate. “I was trying to … put on my historian hat and to look at what might be of interest … years down the road. So in my first book, The Promise, I made a big thing about health care, which became Obamacare. … If I hadn’t, I don’t think the book would hold up as well.”

That first book hit No. 4 on the New York Times bestseller list.

Its follow-up, about the 2012 election, wasn’t so lucky. The story is still significant, he argues, because Obama’s experience with the Tea Party presages Hillary Clinton’s and Joe Biden’s experience with MAGA, “So I was focused on what I still think of as a very compelling election, but nonetheless one of less enduring historical significance than the ones that surrounded it.”

Franklin Foer, a staff writer at the Atlantic, experienced something similar with his recent book about the Biden presidency. What’s significant in Foer’s case is the publication date.

The Last Politician was released on September 5, 2023, and it shows that one of Biden’s strengths as a new president was he could pull the reins on Benjamin Netanyahu’s increasingly flagrant bombing campaigns in Gaza.

“Hey man,” he tells Bibi over the phone, “we’re out of runway here. It’s over.”

“And then,” writes Foer, “like that, it was.”

Note the Old Testament language there. Foer’s doesn’t hide his admiration for the president, and there are moments where the suspenseful, high-stakes tone tilts toward reverence. If writers of these tell-alls are often humbled by the weight of their subject, Foer trends occasionally toward awe; not of his characters, necessarily, but of his larger subject. His access.

On October 7, almost exactly one month after Last Politician’s release, Hamas, designated by many nations as a terrorist organization, invaded Israel and murdered over a thousand civilians. The attack galvanized a military response that Netanyahu has now escalated to the point of nearly 40,000 Palestinian deaths, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry, most of whom are civilians. Protests have sustained around the world.

Does it change much about Foer’s book that the Biden-Netanyahu relationship, once a symbol of the president’s diplomatic savvy, has changed so radically? Sort of.

Does it change much about Foer’s book that the Biden-Netanyahu relationship has changed so radically? Sort of.

But Foer did his research and presented the facts as they were. That those facts had a shelf-life of exactly one month is hardly his fault.

“You always want the timing to work out,” says Alter. “Frank’s book is terrific. It might’ve been overtaken by events on Netanyahu, but it gets deep inside [Biden’s] achievements and what kind of a president he is. … That’s different from the fly-on-the-wall thing,” referring to the more scandal-focused, tabloid-flavor tell-alls we got during the Trump years, such as A Very Stable Genius or Front Row at the Trump Show.

“[That’s] its own genre.”

The first tell-all from the Trump era was Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury. In a subgenre whose titles age so quickly, it’s easy to forget that, at the time of its release, Fire and Fury was a near-Harry Potter-level phenomenon in publishing. On the Thursday before its January 9 release, President Trump sent a cease-and-desist to the publisher, Macmillan, demanding “a full and complete retraction and apology.” Macmillan’s CEO, John Sargent, responded to the letter with a public rebuke, calling Trump’s demand unconstitutional, and bumping the book’s publication to the next day: Friday.

A trolling Wolff tweeted, “Thank you, Mr. President.”

Kramerbooks in Washington, DC, hosted a midnight release, with customers lining up to the back of the store. They sold out in 20 minutes. So did bookstores around the country. Fire and Fury broke a first-week sales record for its imprint, Henry Holt, and Forbes soon estimated that — with his advance, residuals, film, and TV deals — Wolff had earned about $13 million for the project.

Bob Woodward was already working on his own book, Fear, to be released eight months later, but other journalists likely took notice of Fire and Fury’s success, the public’s appetite for a tome of White House insider gossip. They imagined the sort of book they might write, if given a chance; especially considering Wolff’s own less-than-fantastic reputation (one reviewer of Fire and Fury called him “a grotesque Boswell to Trump’s Johnson,” conceding at least to capitalize the J).

The only issue is, who’s got that kind of access?

After Wolff, the Trump administration raised its guard, and hence all subsequent tell-alls (the bestsellers, at least) were written by big names in journalism, reporters who were bound to have access because they were backed by major outlets, like Jonathan Karl (ABC News), Susan Glasser and Peter Baker (New Yorker and New York Times), Carol D. Leonnig and Philip Rucker (both of Washington Post), and Maggie Haberman (New York Times). Each of these authors is a seasoned reporter and theirs are the political insights that inform so much of the voting demographic, but their books were sold on the basis of something more commercially viable: their access.

For all their variety you might find in the details of these books, their introductions are strikingly uniform. The author sets up a scene in medias res, showing themselves engaged somehow with the material (ideally the president himself), after which they posit a thesis and then show their credentials.

That last part, the badge-flashing, happens on a sliding scale of humility and creativity. Jonathan Karl, for instance, opens Front Row at the Trump Show with a Huck Finn-type wonder at what it’s like, on Inauguration Day, to walk through a White House-in-transition, how humbled he is to be there, to conduct the very first one-sentence interview with the president.

It’s simple and it’s charming, but it’s also calculated.

What the author seems at pains to convey through these personal anecdotes is that, though friendly with Trump, he knows the man is dishonest and flashy and vain. Failing to observe these things, he’ll sound naive and therefore unreliable; however, by boasting of his longstanding relationship to Trump in spite of those qualities, he risks suggesting (admitting?) that the way one suffers an opportunistic colleague is by being opportunistic oneself.

Maggie Haberman, meanwhile, opens her own 2022 Trump book, Confidence Man, with a phone call: The setting is 2016 and she confronts Trump over the phone about the fact that his presidential campaign has just been endorsed by David Duke, former grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. After he reads out a press-friendly line — coached, he explains, by “my two Jewish lawyers” — about antisemitism, Haberman asks him if that’s it. Trump responds, in earnest, “What do you need me to say?”

Like Karl’s lonely punctual stroll through the corridors of power, this moment conveys to its reader — in tone, character, power dynamics — that the author is speaking privately with the future president; she’s asking him challenging questions, and he, in turn, is asking her for cues.

Meanwhile, their task is to heighten the reader’s sense of intimacy to the most powerful person in the world. Consider how the cover art for these books all show their subject — Trump and Biden alike — in horrendous pore-gaping closeup. Jonathan Karl’s latest book, tilting the formula, shows instead a fatigued-looking Trump, walking alone, head hanging and necktie loosened, over a stretch of White House lawn at night. Solitary, contemplative, vulnerable.

Scribner, Penguin, Twelve, Twelve, Penguin

Without the perspective of history, the allure of the White House tell-all is the allure of the tell-all itself: voyeurism. Seeing what influential people are doing when they think nobody’s looking. Seeing the powerful brought down and made ordinary.

2024 marks the 50th anniversary of All the President’s Men. After four years of unending scandal in the Trump administration, sparking the White House tell-all back to blockbuster status, it has receded again, under the Biden administration, into a kind of curio. Chris Whipple’s book about Biden’s first two years in office, Fight of His Life, was released on January 17, 2023. As of June 2024, it has sold 5,000 copies, according to BookScan. Foer’s Last Politician, approaching its first anniversary, has sold 13,000. The numbers might not be big, if the president is not himself dramatic or polarizing or all that interesting, but they’re still bestsellers.

Swap out the years, the names, the faces — they all boil down to the most memorable image from The Final Days: Nixon on his knees. Tugging Kissinger down there with him. Drunk. Desperate. “Henry, we need to pray.”

These books show us a powerful figure with his head bowed, kneeling, begging forgiveness of someone unseen.

For the reader, looking down at the page, it’s a great vantage from which to render judgment.

![ROSE IN DA HOUSE I BE MY BOYFRIENDS 2 [OFFICIAL TRAILER]](https://cherumbu.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ROSE-IN-DA-HOUSE-I-BE-MY-BOYFRIENDS-2-OFFICIAL-150x150.jpg)