In a partisan 6-3 ruling issued this summer, the Supreme Court seized the opportunity to gut a cornerstone of federal regulation: Chevron deference, a legal doctrine that for the last 40 years has given government agencies the latitude to implement laws set by Congress. The ruling has given corporations a powerful tool with which to bend government toward their interests and away from those of ordinary Americans. It’s widely expected to imperil the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to limit climate-warming emissions and toxic pollutants, the Food and Drug Administration’s ability to ensure food and drug safety, and the Americans with Disabilities Act’s ability to protect disabled people from discrimination, among many other corners of the regulatory state.

This grave decision emerged from Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, a case brought by commercial fishing companies hoping to do away with federal rules requiring them to pay for government-mandated observers who ensure that they do not overfish. Notorious right-wing billionaire Charles Koch, along with myriad corporate interests, had lined up to support the fishermen’s case, sensing a chance to torch federal regulation of big business. Now, it won’t just be the fish who suffer as a result.

Understanding how Big Meat shapes our democracy

Big Meat spends big money to shape government policy, often at the expense of ordinary people’s health and political voice. Read about just a few of the ways:

This piece is part of How Factory Farming Ends, a collection of stories on the past and future of the long fight against factory farming, and how it might yet make real progress. This series is supported by Animal Charity Evaluators, which received a grant from Builders Initiative.

The ruling has been widely reported and opined on as a watershed moment in American governance — yet few have remarked on the significance of the fishing industry’s role. That role is no coincidence, but rather is emblematic of an alarming, long-running trend: For decades, animal industries, including meat, dairy, and commercial fishing, have been working successfully to undermine democracy and government oversight in order to boost their bottom lines. The US government, meanwhile, at the behest of corporate influence, has spent the last three decades tarnishing animal activists fighting these industries as domestic terrorists, not because they pose a threat to people’s lives (no humans have ever been killed as a result of animal activism) but because of the threat they pose to profits.

They’ve been able to do this, in part, because progressives have too often overlooked the misdeeds of animal industries while buying into the image of animal activists as fringe and extreme — as people who would care more about herrings’ lives than fishermen’s livelihoods. This image, however, is taken straight from the animal industries’ playbook. For decades, corporate actors have worked covertly to divide the animal movement from other progressive causes in order to conquer it.

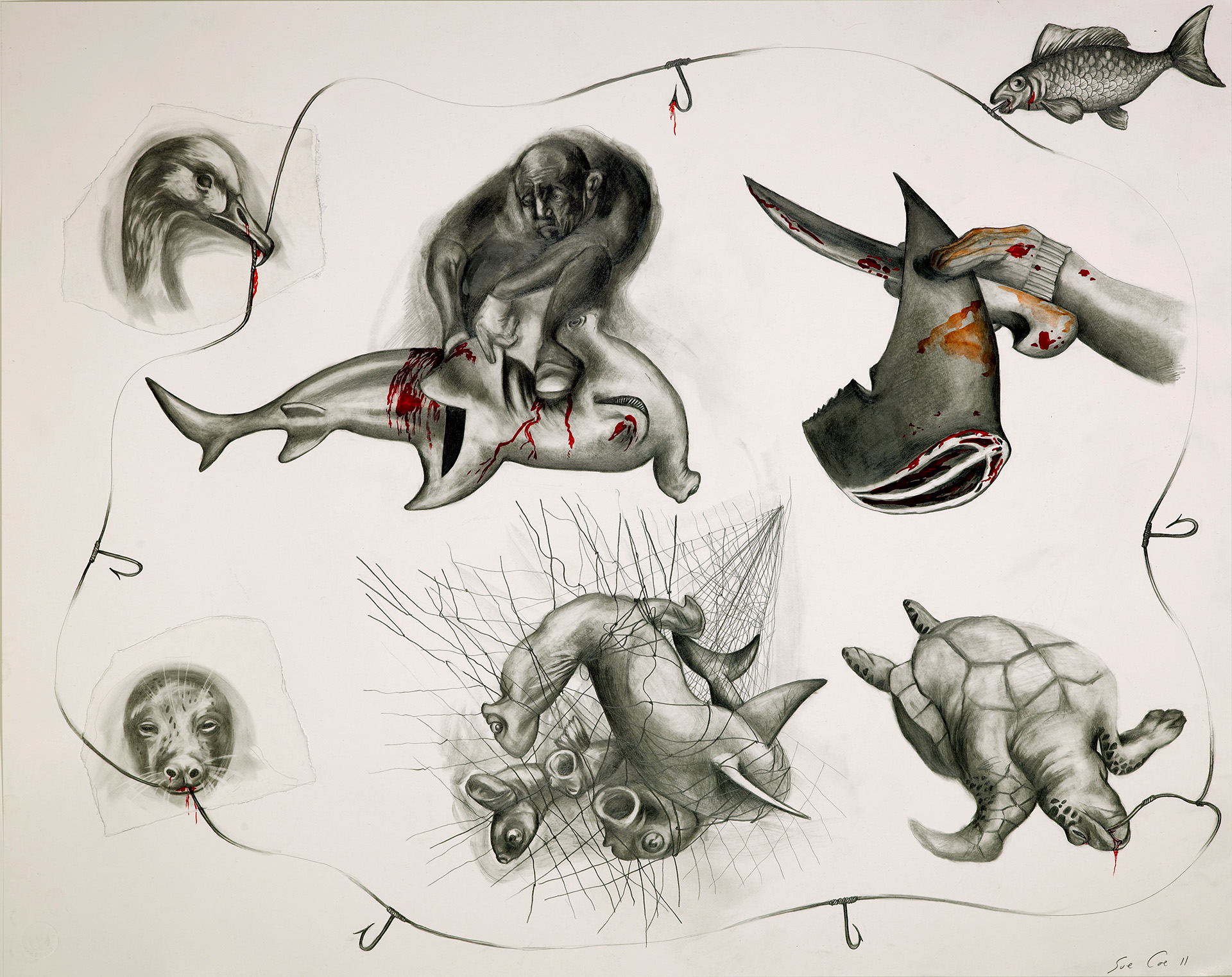

“Fish Hooks and Victims” (2011) by Sue Coe© 2011 Sue Coe/Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

In the late 1980s, for example, the American Medical Association (AMA) promoted a strategy to isolate and derail animal rights activists in order to halt their progress and growing popularity. As Sunaura Taylor, one of the authors of this piece, details in her book Beasts of Burden, the AMA organized a movement of disabled and ill people to promote animal testing — a movement countered by a grassroots group of disabled and ill activists who objected to animal research. The AMA plan, which was never meant to be public, stated, “To defeat the animal rights movement, one has to peel away the outermost layers of support and isolate the hard-core activities from the general public and shrink the size of the sympathizers.”

To build a successful progressive movement, one that can challenge animal industries’ extraordinary corporate malfeasance, the left needs to resist this strategy of divide-and-conquer. By treating concern for non-human animals as a fringe issue, progressives may actually be undermining many of the causes they care about, while also inadvertently emboldening the right and abetting the further erosion of democracy, including attacks on the regulatory state.

It’s often said in animal rights circles that the movement needs buy-in from the broader left to succeed. We agree, but we also believe the reverse is true: For progressive movements to win, they need to incorporate animal rights. Expanding our circle of concern beyond our species will help progressives address many of the urgent challenges of our day, from tackling climate change and protecting public health to reining in corporate power and preserving civil liberties, because animal issues are invariably connected to all of these causes. Given all that is at stake, the left must grow the circle of animal sympathizers before it’s too late.

Americans love animals. Why do our politics trash animal rights?

Americans are broadly united in their affection for animals. According to a 2022 Data for Progress survey, 80 percent of likely voters believe that preventing animal cruelty is a matter of personal moral concern, including 77 percent of Republicans. A third of Americans say they support animals having the same rights as people, a 2015 Gallup poll found, a number that was up from 25 percent in 2008. Yet the systematic exploitation of animals in food production and scientific experimentation is rarely taken up in progressive politics.

By treating concern for non-human animals as a fringe issue, progressives may actually be undermining many of the causes they care about

Take, for example, a groundbreaking recent case of corporate animal abuse. In 2022, the Department of Justice secured the rescue of over 4,000 beagles bred for medical research at a rural Virginia facility operated by the company Envigo. Investigators had uncovered that the dogs were being grossly neglected and mistreated, with animals crowded and sometimes crushed to death in small cages, fed moldy food, and left to languish in their own waste. This past June, Envigo, a leading global supplier of animals used in research, pleaded guilty to crimes including conspiracy to violate the Animal Welfare Act and fined $35 million — the largest fine ever imposed in an animal welfare case. They and their parent company Inotiv, which generated over $500 million in revenue in 2022, are now barred from breeding and selling dogs.

The shocking story garnered headlines in the Washington Post, the Guardian, NPR, and the New York Times. But this landmark win for animal rights was met with a conspicuous indifference by progressive organizations, politicians, and news outlets, who ignored the groundbreaking victory, no matter that the story connects to key issues progressives care about, including corporate misconduct and ongoing attacks by animal industries on the public’s First Amendment right to protest.

A beagle puppy rescued from animal experimentation at Envigo, an animal breeding and research company, which was shut down after federal authorities found numerous animal welfare violations.Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

This silence, however, shouldn’t come as a surprise. Animal advocates are, to use a phrase popularized by the Canadian philosopher Will Kymlicka, “orphans of the left”: Potential allies often do not see justice for non-human animals as a priority, or worse, mock or scorn it.

“Proponents of various social justice movements routinely express support for each other — feminist organisations often show support for Black Lives Matter, or for immigrant rights, or gay rights,” Kymlicka writes, “but animal rights groups remain outside this circle of progressive solidarity.”

Instead of leveraging Americans’ concern for animals to unite against businesses and practices that harm both animals and people, progressive organizations tend to ignore these issues while ordinary leftists too often join the chorus of disdain and contempt directed at activists and movements dedicated to reducing animal exploitation. As the Citations Needed podcast has shown, animal advocates are frequently treated as a “pop culture punchline,” while progressive media, with a few exceptions, rarely cover animal rights.

In this, progressives are wholly united with the right. For conservative pundits and politicians, vegetarian-bashing is a cheap and easy way to offer proverbial red meat to their base. Over the past decade, the right’s hostility toward the LGBTQ+ movement and embrace of white nationalism have grown in parallel to a histrionic fetish for animal products and contempt for those who avoid them (“soyboys,” in the right’s parlance).

The day after President Joe Biden dropped out of the presidential race, the National Republican Senatorial Committee released a memo of opposition research against Vice President Kamala Harris, the now-presumptive Democratic nominee, claiming she wants to ban red meat. Indignant culture warriors routinely warn that socialists are trying “to take away your hamburgers” (along with the gas-guzzling grills they are cooked on) while foisting “lab-grown meat” on a resistant populace — no matter that such products aren’t even on store shelves and won’t be any time soon. In May, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law criminalizing the manufacture and sale of cell-cultivated meats, declaring in a statement that by doing so he was “fighting back against the global elite.” Alabama followed suit, and other states have considered similar bans.

These antics have produced very little pushback from Democrats. Instead, Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) jumped on the bandwagon, tweeting his support for DeSantis’s approach.

We saw a similarly strange dynamic in 2019 after Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) announced her groundbreaking proposal for a Green New Deal. Republicans went ballistic about the supposed threat to carnivory: “They want to take away your hamburgers,” fumed former Trump adviser Sebastian Gorka. On an episode of the talk show Desus & Mero, Ocasio-Cortez assured viewers that her plan did not involve “forc[ing] everybody to go vegan or anything crazy like that.” Rather than assuaging her opponents, her comments only affirmed the view that veganism is marginal and extreme.

Ocasio-Cortez isn’t alone in thinking that being associated with an anti-meat, pro-animal ethos is a bridge too far. Abundant, cheap meat is unquestioned orthodoxy across the political spectrum; decades of government-subsidized animal agriculture and a culture that glorifies meat-eating have made animal rights a third rail in American politics, helping to isolate the animal rights movement from the broader progressive ecosystem, even the left wing of the Democratic Party, and even when reining in factory farming would benefit the people that the Democratic coalition represents.

In November, residents of Sonoma County, California, will vote on Measure J, a first-of-its-kind ballot initiative to ban concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), or what are typically called factory farms. If passed, the measure would compel approximately two dozen livestock operations to close or downsize over three years, according to the Coalition to End Factory Farming, a group that formed to support the measure. While various public health organizations and even some Democratic politicians (most notably New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker) have called for the phase-out of CAFOs — which are notoriously harmful to animals, human workers, and the environment — the Sonoma County Democratic Party has come out opposing the measure.

We could also look to the pork industry’s ongoing, nearly six-year campaign to invalidate California’s Proposition 12, a law that requires animals typically kept in tiny cages on factory farms to be given a modicum of space to move around. The pork industry’s case against Prop 12 before the Supreme Court last year threatened to overturn the will of an overwhelming majority of California voters, and to take down hundreds of progressive state and local regulations across the country along with it — but that did not stop the Biden administration from filing a brief in support of the pork industry’s right to confine pregnant pigs in cages barely larger than their bodies. (Prop 12 ended up being upheld, but the industry’s effort to invalidate it through other means continues.)

Unfortunately, the animal rights movement may be partly to blame for its relative isolation. Mainstream vegan advocacy tends to emphasize individual consumer choice, thereby turning what should be a liberation movement into little more than a lifestyle defined by a particular shopping list.

While we certainly encourage people to purchase oat- or nut-based alternatives instead of dairy or to purchase cosmetics produced without animal testing, we ultimately see veganism as part of a more far-reaching, socially transformative agenda. As we have written elsewhere, we believe that animal rights activists need to connect their cause to larger issues of corporate exploitation and profit maximization — in other words, to the market forces that deepen socioeconomic disparities and that are now hurling humanity over an ecological cliff.

Progressives also need to be attuned to the ways speciesism, a belief in the superiority of human beings, reinforces other forms of human hierarchy, including racism, colonialism, ableism, and sexism. While the animal rights movement may have a long way to go in realizing these goals, the converse is also true: progressives must recognize that animal exploitation has serious implications for the broader movement that can no longer be ignored.

Big Meat has led the charge to undermine democracy and criminalize dissent

The appalling impact of animal industries on the environment and human health are well known: methane emissions that drive a warming climate, deforestation, water pollution, biodiversity loss, antibiotic resistance, zoonotic diseases that could spark future pandemics, the catastrophic effects on the ocean’s biological systems of overfishing; the list goes on. Those industries also lead to the horrific exploitation of workers, largely immigrants and people of color — and often children — who are paid poverty wages and endure exceedingly high rates of injuries and psychological trauma while working in commercial fishing, factory farms, and meatpacking plants. Vox has reported on the devastating impact of the pork industry on Black communities in rural North Carolina, where people are outnumbered by pigs by as much as 35:1, and are sickened by enormous lagoons of swine feces and other environmental contaminants.

What is less well known is that Big Meat is also busy undermining democracy. Globally, animal agriculture is a $2 trillion business, amply supported by government subsidies, and companies fiercely lobby around the world to protect their interests. Meat and dairy companies and industry trade groups have spent millions of dollars in recent decades to derail climate action and block animal welfare legislation. Their campaigns have spread disinformation while bankrolling politicians, and, as Vox recently detailed, university scientists who advance their agenda.

Big Meat’s agenda increasingly focuses on suppressing First Amendment rights, whether by pushing to make it illegal for plant-based dairy alternatives to use the word “milk” in their marketing or to criminalize undercover investigations on factory farms under so-called ag-gag laws. The industry has close relationships with law enforcement and in recent years has helped deploy disproportionate police force against animal rights activists.

US government repression of activism stretches back many decades, including the FBI’s now-notorious COINTELPRO surveillance and sabotage of the Black power, peace, and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. More recently, animal rights campaigns have been a “canary in the coal mine” for government repression of activism, having first been targeted with the nebulous charge of “domestic terrorism” in 1987, journalist Will Potter documents in his 2011 book Green Is the New Red. Yet, progressives have remained relatively silent about this record — perhaps because they saw animal rights as marginal and disconnected from other issues and did not anticipate how the attacks on animal rights activists’ civil liberties and protests would inevitably spread to other arenas.

Beginning in the 1990s, undercover investigations by activists exposed widespread abuse and neglect of dogs, cats, and primates used for animal experimentation, including at Huntingdon Life Sciences, then Europe’s largest animal testing laboratory, where now-infamous footage showed a lab worker punching beagle puppies in the face. Huntingdon Life Sciences tested all manner of substances on animals, including household cleaners, dyes, flame retardants, pesticides, and cosmetics; it was one of the companies that, in 2015, merged to become Envigo — the corporation that, until recently, was breeding and abusing thousands of beagles in Virginia. Animal experimentation was, and remains, part of a multibillion-dollar international industry that involves a complex and expansive network of pharmaceutical companies, chemical manufacturers, government agencies, and factory-farm-style dog breeding mills like the one Envigo operated.

Only months after the twin towers fell, the FBI identified the animal rights movement as America’s No. 1 domestic terrorism threat

As the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) campaign gained momentum in the UK and the US at the turn of the millennium, tanking the company’s public reputation and share price, industry and government snapped into action. As Alleen Brown explains in the Intercept: “The fur and biomedical industries had spent years lobbying the Justice Department and lawmakers to go after eco-activists, who had damaged their property, held audacious demonstrations decrying their business activities, and cost them millions of dollars.” Industry groups seized on the attacks of September 11, 2001, to advance their longstanding agenda. Only months after the twin towers fell, the FBI identified the animal rights movement as America’s No. 1 domestic terrorism threat.

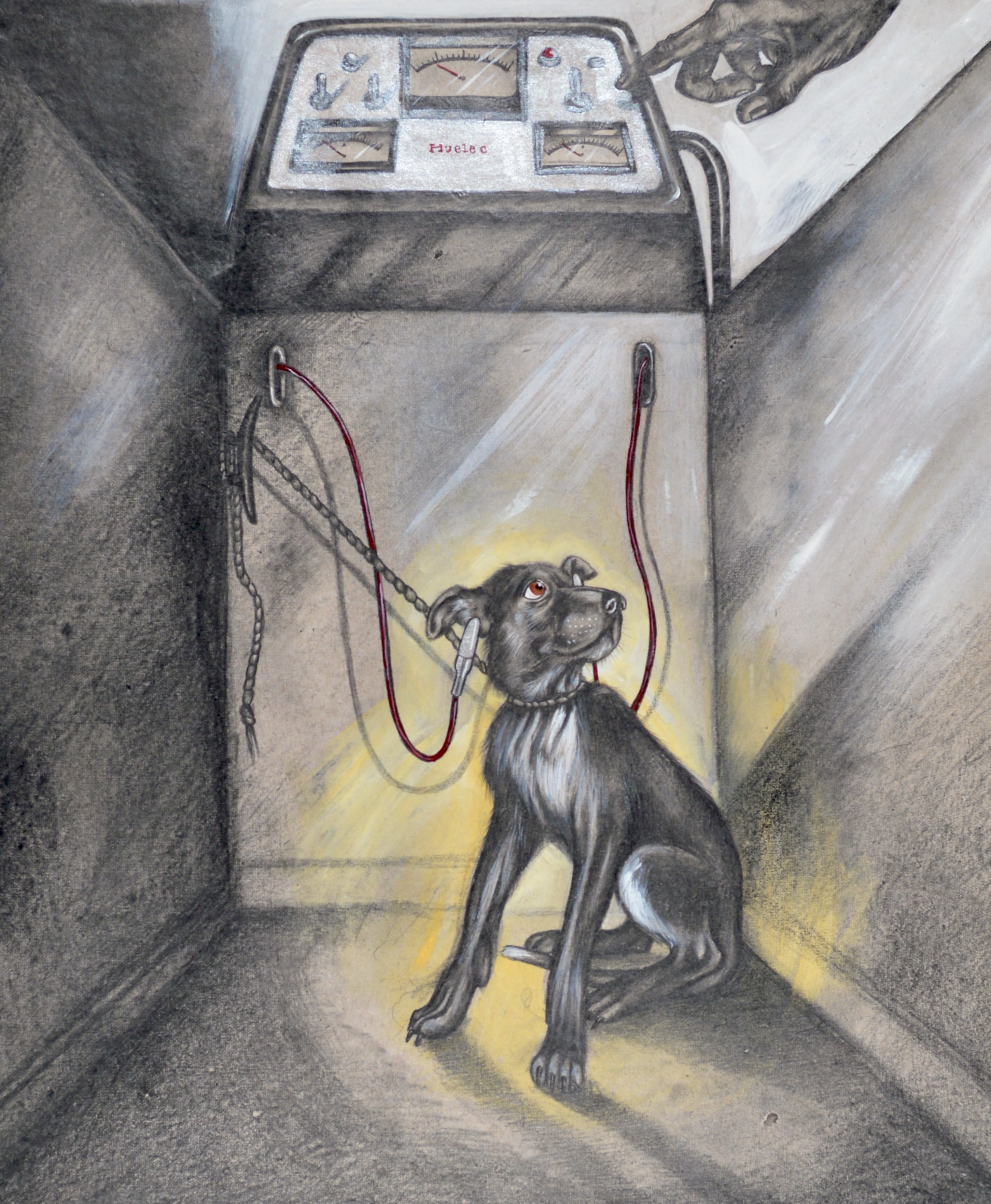

“Flick of a Switch” (1998) by Sue Coe© 1998 Sue Coe/Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

In 2004, then-deputy assistant director of counterterrorism for the FBI, John E. Lewis, testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that there was a growing threat of animal rights extremists and that current terrorism laws were inadequate: They could not address the aboveground tactics used by groups including SHAC — namely, exposing industry wrongdoings and publicizing underground efforts (which included releasing animals from breeding facilities or laboratories, vandalism, setting off smoke and stink bombs, and more).

But even as they argued for expanded powers, federal authorities were pursuing SHAC activists under existing laws. In 2006, a group of defendants, known as the “SHAC 7,” were convicted under the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, a 1992 statute that criminalizes so-called “animal enterprise terrorism.” None were found to have been directly involved in any illegal acts, though they did participate in protests and share information online, including information prosecutors alleged was threatening to Huntingdon associates — evidence, according to the prosecution, of a criminal conspiracy. The activists were imprisoned, sentenced to up to six years, for free speech activities alone.

These activists were targeted because their activities and their convictions — which went beyond objecting to animal abuse to challenge the idea that nonhuman animals should be treated as commodities under any circumstances — threatened industry practices and profits. As Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK) made clear in 2005, authorities feared that animal liberation activists would “move to the timber industry or the defense industry or some other controversial industry.”

To prevent this escalation, the Animal Enterprise Protection Act was amended to become the 2006 Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, which expanded government powers and defined a terrorist as someone who engages in interstate activity with the intent of causing damage to an animal enterprise, including economic damage such as the loss of profits — a definition capacious enough to cover many forms of peaceful protest.

Today, law enforcement and legislators of both parties are applying these repressive tactics to a new generation of activists. In 2017, the FBI’s counterterrorism division named “Black identity extremists” as a growing threat, citing increased attention to police brutality and racial injustice. This overreach is now on stunning display in Georgia, where more than 40 activists involved in the movement against “Cop City” — a $90 million police training facility that will raze a portion of Atlanta’s South River Forest — are facing domestic terrorism charges for alleged trespassing and property damage. They are the first people to be prosecuted under a 2017 state statute that created more punitive consequences (up to 35 years in prison) for, in the words of the ACLU, “property crimes that were already illegal, simply because of accompanying political expression critical of government policy.”

Trump’s potential powers to criminalize protesters would be less acute if people hadn’t looked the other way when animal rights activists were first being targeted

In recent years, numerous states have expanded, or attempted to expand, domestic terrorism statutes in similarly worrying ways. This year, for example, some New York Democrats responded to pro-Palestine protests by proposing legislation that would turn blocking public streets or bridges into acts of domestic terrorism.

Should Donald Trump take power next year, activists will likely face more hostility from government. The former president has expressed support for labeling antifa (short for anti-fascist) a terrorist organization — no matter that it is an ethos, not an actual group — as well as a desire to use the Insurrection Act, a 1807 law that would allow him to deploy the military to crush demonstrations he doesn’t like. Government’s potential powers to criminalize protesters would be less acute if people hadn’t looked the other way when animal rights activists were first being targeted decades ago. “The unprecedented repression of animal rights activists as ‘terrorists’ has become the post-9/11 model for criminalizing protest,” Will Potter told us. “This is the new corporate playbook. The most important lesson we can learn from it is that, unless we fight back, it will put everyone at risk.”

Animal rights can help build a unified progressive movement

The right correctly understands all progressive causes as connected; that’s why it is working to make compassion for animals part of its broader culture war, while also busily attacking organized labor, environmentalists, immigrants, gay and trans people, feminists, teachers of “critical race theory” and proponents of “DEI,” and students protesting for peace in Gaza. The left must respond in kind, by treating these issues as interconnected and in need of holistic solutions.

There’s precedent for this approach. Animal advocacy has not always been cordoned off from other causes, and history offers numerous compelling examples for today’s activists. Indeed, one of the first American vegans we know of was Benjamin Lay, who authored one of the earliest American anti-slavery books, challenged both racial and gender hierarchies, and helped push the Quaker church toward abolition with his bold activism. His compassion for animals was so intense that he not only refused to eat them, but also refused to travel by horse, walking everywhere by foot.

As Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy document in their new book Our Kindred Creatures: How Americans Came to Feel the Way They Do About Animals, the 19th-century movement for animal welfare was galvanized by the victory against slavery — many reformers of the day saw abolition, labor rights, democratic reform, women’s suffrage, and concern for animals as interlinked. The earliest American anti-vivisection campaigns, beginning in the late 1800s, were run by women who connected their own domination with the plight of animals undergoing experimentation. At the time, women exerted little control over their own bodies, and male doctors often prescribed invasive surgeries such as ovariectomies and hysterectomies for diagnoses including hysteria.

“For some Victorian women, images of the vivisected animal strapped to a table bore an uncanny and frightening resemblance to the gynecologically vivisected woman,” historian Diane Beers writes. “As women agitated for greater rights, this analogy of shared oppression linking themselves and animals provided a powerful motivation for their critique of the dark side of a decidedly patriarchal profession.”

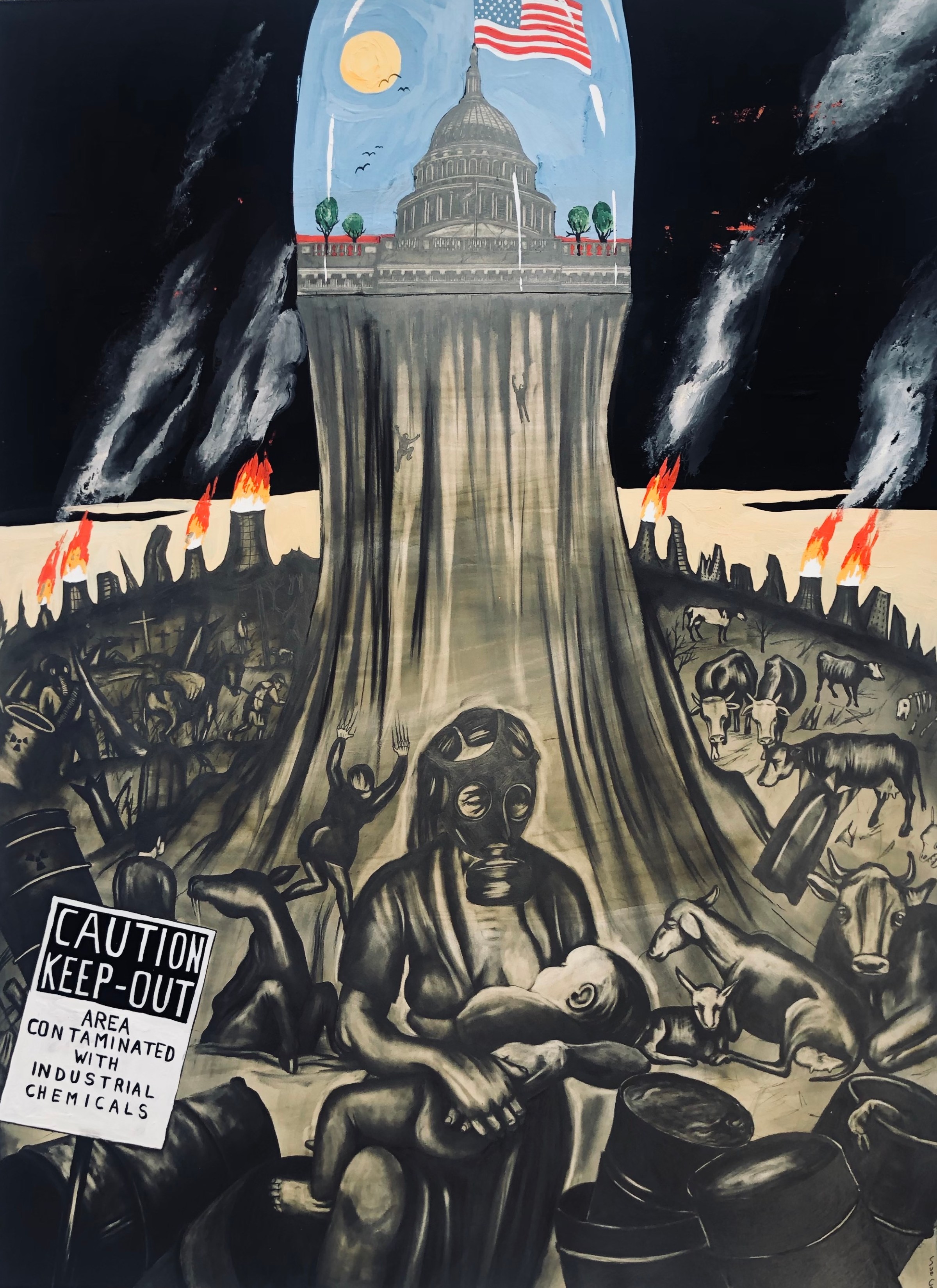

“A Cut Above the Rest” (1992) by Sue Coe© 1992 Sue Coe/Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

A similar cross-pollination of progressive causes happened again in the later part of the 20th century. The modern animal rights movement took shape at the crest of a wave of campaigns demanding rights for historically marginalized groups, which prompted some people to realize that non-human creatures are oppressed too; the term speciesism was coined in 1970. The SHAC campaign took inspiration from the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements, which used boycotts and divestment to inflict economic costs on their opponents. SHAC activists successfully pressured dozens of suppliers, insurers, and lenders to cut ties with Huntingdon in order to make it impossible for the company to engage in business as usual. This financial savvy, inspired by earlier generations of organizers, is what made the campaign so effective, and so threatening.

Despite prolonged suppression and vilification, the animal rights movement has endured. Meanwhile, millions of ordinary people object to animal suffering — even if they continue to consume animal products and don’t yet see the suffering of a beloved pet as analogous to the suffering of an animal raised for research, let alone the pig, cow, chicken, or fish dead on their plate.

With encouragement, they might begin to connect the dots — not just between the suffering of different animal species but also between the exploitation of animals and larger systems of oppression. Recall the recent bipartisan outrage over Republican South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, who boasted in her autobiography about shooting her difficult-to-train puppy Cricket. What if progressives had leveraged that moment of shock and horror to make the case that Noem’s disregard of a young dog’s life is not an aberration, but rather connected to the right wing’s disregard for life and embrace of violence in other arenas, including attacks on reproductive autonomy, immigrant rights, and democracy as we know it?

It’s notable, too, that Noem’s cold-blooded but isolated killing sparked far more public outcry than revelations of Envigo’s profit-driven disregard for animal life — or reports that vice presidential candidate and faux-populist Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) has investments in a biotech startup that tests on live animals, leaving monkeys with burnt paws and genitals and, in at least one case, killed by faulty lab equipment. That news, like the Envigo story, offers an opportunity to connect the abuse of animals to the need to curtail corporate abuses more broadly.

Given the high political stakes, including the threat of a second Trump term, the left needs to seize every opening to grow our movements. Instead of perpetuating the narrative that animal liberation activists are extremists who are not impacted by or attuned to other systemic harms, the time has come to recognize that far more Americans are actually animal advocates than we think. Doing so will strengthen struggles for environmental sustainability, racial and disability justice, restraining corporate power, and — perhaps most urgently — protecting our right to dissent.

Sunaura Taylor is an artist, writer, and academic. She is author of Disabled Ecologies: Lessons From a Wounded Desert and Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation, which received the 2018 American Book Award.

![ROSE IN DA HOUSE I BE MY BOYFRIENDS 2 [OFFICIAL TRAILER]](https://cherumbu.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ROSE-IN-DA-HOUSE-I-BE-MY-BOYFRIENDS-2-OFFICIAL-150x150.jpg)