What does British Airways’ recent decision to suspend its London-Beijing route have to do with the war in Ukraine? How does the Israel-Palestine conflict lead to cargo ships with containers falling overboard in rough weather off the southern African coast? What does an earthquake in Tonga tell us about the vulnerability of Taiwan’s communications infrastructure?

Each are examples of the strain armed conflict is putting on the physical infrastructure that makes our world move — and work.

In an era of increasing armed conflict and rising superpower tension, some fundamental ideas about the way the global economy works are coming into question. Global trade, rather than bringing countries together as advocates of globalization once hoped, is increasingly being weaponized by states against each other. Sanctions are splitting sectors of the global economy, notably energy markets, in two. The internet, once touted as an open realm where state power would have no sovereignty, is increasingly balkanized along national lines.

When we talk about globalization, we tend to focus on the movement of people, products, money, and information. But none of that is possible without the physical systems that makes those exchanges possible: The container ships that move goods from factories in Asia to stores in America; the flying, steel behemoths that make it possible to have breakfast in Abu Dhabi and dinner in Paris; the undersea cables that make your Zoom calls, Amazon orders, and online gaming sessions possible.

Increasing armed conflict and geopolitical tensions, from the Red Sea to the Arctic Sea, are threatening this infrastructure, putting an unprecedented strain on the global supply chains of goods, people, and data. So far, the physical network we rely on to keep the global economy functioning has held up under the pressure, but the companies and officials tasked with maintaining that network are bracing for what’s to come amid growing concerns that the system may be more fragile than it appears.

On July 9, the Malta-flagged container ship Benjamin Franklin, owned by the French shipping company CMA CGM, ran into bad weather off the southern coast of Africa, losing 44 containers overboard. The incident happened just a few days after another ship ran aground off the coast of Cape Town. These accidents are a reminder of why ships traditionally would rarely risk sailing around the stormy tip of Africa when it’s winter in the Southern Hemisphere — and why an unusual number of ships are doing so anyway.

Since last November, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have been attacking shipping in the Red Sea, using drones and missiles, and even seizing some vessels. The Iranian-backed militants, who control much of Yemen’s territory, including its capital, say they are attacking only targets linked to Israel, acting in solidarity with their allies in Hamas and the people of Gaza, though many of the ships they’ve attacked have little or no connection to Israel. Since the strikes began, two ships have been sunk and three sailors were killed in a missile attack on another. The attacks have continued despite a months-long effort by a US-led international military coalition to prevent them by intercepting projectiles as well as attacking launch sites in Yemen.

The danger is such that around two-thirds of the ships that normally sail through Egypt’s Suez Canal, transiting between Asia or the Middle East and Europe, have been diverted around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, adding thousands of miles and weeks of extra travel time to their trips. In essence, the Houthis have helped roll back shipping by over 150 years, before the Suez Canal was opened in 1869, when ships between Europe and Asia had no choice but to go around Africa.

A Ryanair passenger plane from Athens, Greece, that was intercepted and diverted by Belarus authorities in 2021.Petras Malukas/AFP via Getty Images

The delays and uncertainty have created significant downstream effects, including congestion at some ports, shortages of shipping containers, and higher freight rates, at times more than twice the normal costs. Egypt, which normally earns about $9 billion in transit fees through the Suez Canal, has lost around 40 percent of that revenue.

But more than merely increasing the cost and the time of shipping, the Houthi attacks have disrupted one of the foundations of the current era of globalization: the certainty of the sea lanes.

“We’ve been banking on this idea that you can move cargo anywhere around the world within a set period of time,” says Sal Mercogliano, a former merchant mariner and shipping historian at Campbell University. “Now you can’t be so sure.”

The Red Sea, choked off at the north by the Suez Canal and at the south by the narrow strait between Yemen and East Africa known as Bab al-Mandab, is one of the world’s key shipping routes: in a normal year, about 12 percent of global trade and 10 percent of the maritime oil trade travels through its waters.

The route has been blocked before — notably, in 2021 when a container ship ran aground in the Suez Canal, blocking traffic for a week. But this time it’s different. Even if the war in Gaza were to end tomorrow, there’s no guarantee that the Houthis, who have a variety of demands from and grievances with regional powers and the international community, would simply give up the leverage they’ve suddenly seized. And there’s no guarantee the international community could force them to.

Nils Haupt, director of corporate communications for Hapag-Lloyd, a major German shipping company that saw one of its vessels attacked by the Houthis in December, told Vox it was impossible to say what set of circumstances would convince the company it was safe to use the Red Sea again.

“Who is going to be the first shipping line telling their sailors, ‘Okay, as of tomorrow we go through the Red Sea’? We won’t be the ones,” Haupt says. “If you ask me how long this will last, I will give you the same answer that any military person or any insurance company would give you: nobody knows.”

It’s not only shipping companies that have to adjust, says Noam Raydan, an expert on Middle Eastern shipping and energy at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. As part of its grand Vision 2030 economic development initiative, the Saudi Arabian government recently launched a major project to improve the competitiveness of its ports in hopes of becoming a logistics hub for the global shipping industry. Middle Eastern gas producers have been vying to increase their share of the European market with the war in Ukraine prompting many European countries to reduce their dependence on Russian gas. All of that depends on stability in the Red Sea.

“I don’t see us going back to normal,” Raydan told Vox. “This is a new situation. I don’t see it going back to what it was before October.”

The Red Sea is far from the only chokepoint for global shipping. Concerns are also growing about potential Iranian disruption to the Strait of Hormuz, between the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman, which is even more vital to the international energy trade and which has seen naval combat in the past.

The Red Sea crisis follows a threat to shipping in the Black Sea following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Moscow’s attempt to effectively blockade Ukraine’s ports in 2022. Other conflict threats to major global shipping lanes, including the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea, are still theoretical, but can’t be ruled out.

“The oceans really have been threatened in a major way, and now what we’re seeing is multiple issues causing delays and diversions across the planet,” said Mercogliano. “The fear is that there may be more on the horizon.”

Debate all you want about Russia’s economic, political, or military might. There is no denying one thing: the country is very, very big, with a land mass of more than 6.6 million square miles. And since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, that chunk of the globe — or rather, the airspace over it — has suddenly become off-limits to many of the world’s airlines.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe, Canada, and the US closed off use of their airspace to Russian carriers. Russia responded in turn by restricting its own airspace to airlines from those countries.

“Basically, it’s resulted in putting up a ‘Do not enter’ sign on a tenth of the world’s geography,” Steve Morrissey, vice president for regulatory and policy at United Airlines, told Vox.

These airlines have no choice but to go around Russia, which has added up to four hours to some flights between destinations in Europe and Asia, increasing costs due to the greater fuel use and crew time. Some North America-to-Asia flights are more than 40 percent more expensive now than they were before the war began. For US airlines, it’s made some previously popular routes, such as flying directly over the North Pole from the East Coast of the US to East Asia, or from the West Coast to India, impossible.

The result is not just much longer flights, but fewer of them. Prior to the airspace closure, United had operated four daily routes between the US and India and was planning on adding a fifth. Now, it’s operating only one.

Temporary airspace closures due to armed conflict or geopolitical tensions are not new, though usually it’s less a matter of political policy than risk avoidance by the airlines. The downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 by Russian-backed separatists over eastern Ukraine in 2014 was a chilling demonstration of why airlines skirt conflict zones.

But John Grant, chief analyst at OAG, a firm specializing in global flight data, says the Russian closure represents something new for the industry. “We’ve had pieces of African airspace that have been closed while civil wars have been going on, pieces of airspace in the Middle East during particular conflicts, Israel in recent times, but nothing that has been this long and this lasting,” he says.

United’s Morrissey says that the increasing number of armed conflicts spread across Eurasia is playing havoc with some routes, such as from the US to India. “In addition to Russia, the airspace that you have to transit is already kind of like a zigzag. There’s more and more airspace all the time that’s off limits.”

Not all airlines are barred from these routes. Carriers like Air India, Emirates, and China Eastern Airlines are still using Russian airspace to fly shorter and cheaper routes from North America to Asia. US carriers say this is an unfair competitive advantage and have called for the US government to restrict these flights.

But entering that airspace still bears risks — albeit potentially more for passengers than the airlines themselves. On two different occasions since the war began, Air India flights between Delhi and San Francisco were forced to make emergency landings in Russia. In both cases, the passengers, including a substantial number of US citizens, were picked up and taken to their final destination without incident.

It could have gone differently. Back in 2021, authorities in Belarus forced a Ryanair flight transiting its territory to land, and arrested a dissident Belarusian journalist on board. Given Russia’s practice in recent years of using detained US citizens as bargaining chips, including those released in this month’s massive prisoner swap, it’s not outlandish to think they could do something similar.

During the Cold War, there were also times when international air travel was affected by global conflict, including a tragic 1983 incident when a South Korean airliner was mistakenly shot down by Soviet jet fighters. But the scale and importance of air travel has grown massively since then. In 1990 about 300 million passengers per year flew international flights. By 2019, it was 1.9 billion.

This growth has depended on relatively open and uncontested skies, a dividend of the global peace that largely followed the Cold War. When flying across the globe, most passengers likely don’t give too much thought to the countries they’re flying over, or the flag of the airline they’re flying on. But even at 40,000 feet, you’re not entirely free from the politics down below.

When the cargo ship Rubymar was sunk by a Houthi missile attack on March 2, the impact went beyond the shipping industry or even the potential for serious environmental damage in the Red Sea. US officials believe that as the ship sank, its anchor dragged along the bottom of the sea and severed three telecommunications cables. The incident had a significant impact on communications and internet traffic, forcing carriers to reroute up to a quarter of the total traffic between Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, causing significant delays.

The damage to the cables was almost certainly not deliberate sabotage by the Houthis, simply an unanticipated consequence of their offensive, but it was a reminder of both the importance and the vulnerability of underwater infrastructure. It’s an issue of growing concern for defense researchers, and the sinking of the Rubymar is not the only recent incident that has raised that concern.

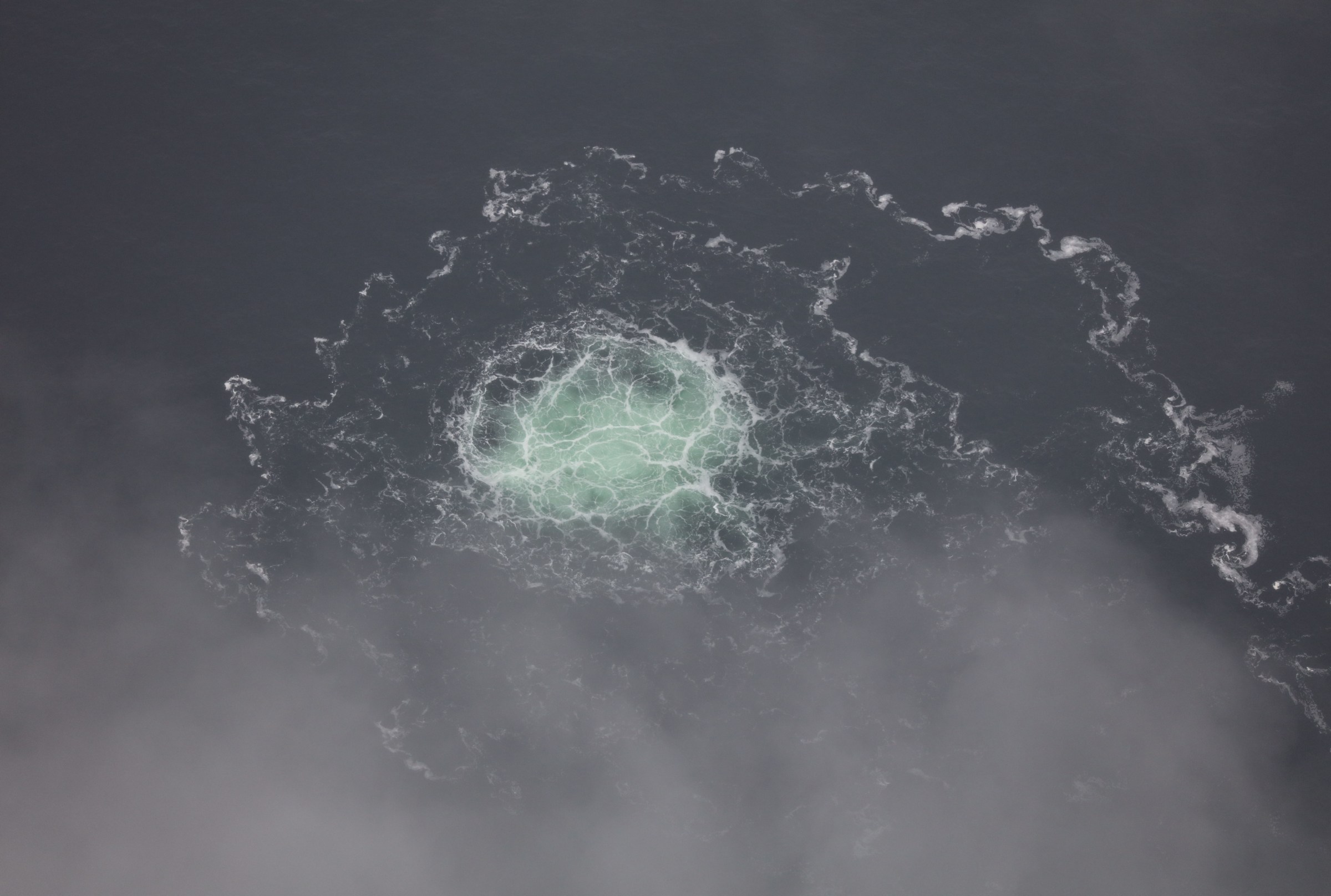

The release of gas emanating from a leak on the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea on September 28, 2022.Swedish Coast Guard via Getty Images

In January 2022, the northernmost undersea fiber optic cable in the world, connecting Norway with the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, was unexpectedly severed. The cable — one of two — not only provides internet to settlements on Svalbard, which sits some 1,200 miles from Oslo, but to a major commercial satellite station used by corporate and government customers around the world. Norwegian police say they believe the cable cut was caused by human activity. While no suspects have been named, Svalbard has been the subject of dispute between Russia and Norway.

In 2023, a gas pipeline along with two telecommunications cables connecting Finland and Estonia across the Baltic Sea was severed as well. Finnish authorities say it was caused by a Chinese container ship, the Newnew Polar Bear, dragging its anchor across the Baltic seabed. “I’m not the sea captain,” Finland’s minister for European affairs told Politico. “But I would think that you would notice that you’re dragging an anchor behind you for hundreds of kilometers. I think everything indicates that it was intentional.” This month, Chinese authorities admitted that the Newnew Polar Bear was responsible for severing the cables and the pipeline, but claimed it was an accident.

Also in 2023, cables providing internet to Matsu, an outlying Taiwanese island close to mainland China, were severed. The Taiwanese government blamed two Chinese commercial vessels and alleged sabotage.

Cables aren’t the only undersea infrastructure that have proven vulnerable to sabotage in recent years. Most famously, the controversial Nord Stream pipelines, built to transport gas between Russia and Germany, were sabotaged in 2022 by underwater explosions. No one has been definitely identified as responsible, though US and European media reports have indicated it was likely pro-Ukrainian groups, with some degree of involvement by Ukrainian intelligence. The pipelines, which increased European reliance on Russian gas and bypassed Ukraine’s own pipeline network, were always extremely unpopular in Kyiv.

There’s a long history of undersea communications sabotage. One of Britain’s first actions during World War I was to cut Germany’s telegraph cables. But the scale at which modern communications relies on these undersea cables is unprecedented.

According to the monitoring firm Telegeography, there are nearly 870,000 miles of undersea cables currently in operation. These can range from the 80-mile cable between Great Britain and Ireland to the 12,400-mile Asia-America Gateway Cable. According to some estimates, as much as 97 percent of intercontinental data traffic passes through this undersea network.

“People usually think their mobile phone call is going through the air, or that ‘the cloud’ is in the air,” Alan Mauldin, research director at Telegeography, told Vox. “The cloud is under the sea, guys.”

Mauldin says that while satellite internet services like Elon Musk’s Starlink can provide backup in places like the small Pacific island of Tonga, which lost internet when its cable was damaged by volcanic eruption in 2022, satellites simply aren’t feasible for the amount of bandwidth demanded by major economies.

The good news is that this network is fairly resilient. Cables fail or are damaged all the time for reasons that have nothing to do with war or politics, such as underwater earthquakes or intrusive sea life. With the exception of very isolated places like Tonga, there are usually multiple cables connecting countries, and it would be difficult to wipe out a nation’s internet access entirely.

But some officials have raised concerns that severed cables could slow communications between allies in an emergency. NATO commanders have warned that Russia may be improving its ability to carry out undersea communications attacks. The island of Taiwan’s undersea cables are also a particular concern, considering that many of them actually lead directly to mainland China.

“If you’re seeking to ambiguously attack and disrupt Western society, then undersea cable is almost a perfect target, because they’re so ubiquitous, and we rely on them so heavily,” said Sean Monaghan, a former UK defense official now with the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The good news is that all these risks have so far been manageable. Cable cuts have caused only brief delays and outages. The shipping industry has been under strain due to the Red Sea crisis, but we haven’t seen anything like the massive container ship pileup at ports like Long Beach caused by the Covid pandemic. A layover at LAX on a flight from New York to Shanghai is not the end of the world.

But these situations show how new areas of vulnerability to conflict are emerging. In recent years, some scholars have discussed an idea known as “weaponized interdependence,” to describe how economic ties between nations can make some countries vulnerable to coercion. Usually this refers to trade sanctions or cutting countries like Russia off from certain financial transactions.

But the ties between countries can be physical as well. “This interdependence between countries provides many benefits and advantages, but at the same time, vulnerabilities,” says Monaghan. “The attack surface of Western societies is very, very large.”

In other words, the very materials we’ve used to build a prosperous and largely peaceful global society have also given us more targets that need protection.