Video vixens posing by a pool. Celebrities and socialites crammed together on couches. Endless bottles of high-end champagne.

October 31, 2024:

Video vixens posing by a pool. Celebrities and socialites crammed together on couches. Endless bottles of high-end champagne.

These are just some of the indelible images that emerged from Sean “Diddy” Combs’s annual White Parties from the late ’90s to the late 2000s. Splashed across magazines and gossip columns, they cemented him as hip-hop’s foremost party boy.

Out of all his roles as a public figure — producer, rapper, fashion designer, actor, media mogul — hip-hop’s Dionysus might be proving to be Combs’s most crucial and damaging one. Nearly a year after his ex-partner Cassie Ventura accused him of physical and sexual abuse, Combs has been hit with a barrage of disturbing allegations and lawsuits. He currently sits in jail without bond on federal charges of sex trafficking and racketeering. What were once portraits of Black wealth and excellence at his illustrious parties have now become sites for scrutiny and criminal inspection.

Online sleuths have spent the past year examining photos from Combs’s Labor Day bashes and other lavish events with the same intensity applied to Jeffrey Epstein’s plane logs. It’s nearly impossible to scroll through X or TikTok without seeing posts of Diddy cuddled up with various celebrities with some unspoken implication that they were involved with his alleged misdeeds.

Regrettably, this online game of “who knew what?” has fully veered into QAnon-esque territory, overshadowing legitimate concerns of complicity among Combs’s closest peers. However, the public’s obsession with Combs’s relationships underscores something difficult to grapple with: How did someone who now appears so monstrous attract so many different people into his orbit?

The story of Combs’s rise and fall exposes the many fractures in a legacy that pop culture was always eager to exalt. Was Combs actually a groundbreaking, one-of-a-kind genius, or just a crafty predator? Was he a charitable force in Black culture, or someone who took credit for other people’s contributions?

These questions give hip-hop fans another thing to reckon with, in addition to all of the upsetting claims against Combs. Most of all, they highlight the way society has idolized the Black entrepreneur at the expense of Black artists and the people below him.

Combs proved to be a master of myth-making throughout his career, starting with his upbringing. Combs was born in Harlem in 1969 to a notorious drug dealer, who was shot and killed when Sean was 3 years old, and a mother who juggled multiple jobs to provide for Combs and his sister. While Combs often painted a completely hard-knocks portrait of his childhood — in one viral anecdote, he claimed he woke up one morning with “15 roaches on his face” — he spent a good part of his adolescence in a relatively safe, middle-class environment in Mount Vernon, New York, attending Catholic schools.

In high school, Combs was swindling his classmates out of their spare change, in addition to creating other hustles for himself. He was also developing a love for the emerging genre of hip-hop. At Howard University in the late ’80s, he became a successful party-thrower on campus, eventually luring hip-hop luminaries like Heavy D, Doug E. Fresh, and Slick Rick. He would get his first industry bona fides at Uptown Records under the tutelage of founder Andre Harrell. There, he made the jump from an unpaid intern to a talent director, helping to develop artists like the all-male R&B group Jodeci and Mary J. Blige.

His stint at Uptown was also where he experienced his first of several PR catastrophes. In 1991, he co-hosted an AIDS fundraiser with Heavy D at the City College of New York that was grossly oversold and resulted in a stampede that killed nine people. While this hardly stopped Combs’s momentum, this event can be viewed as a part of a pattern of collateral damage that Diddy was willing to leave behind on his path to industry dominance.

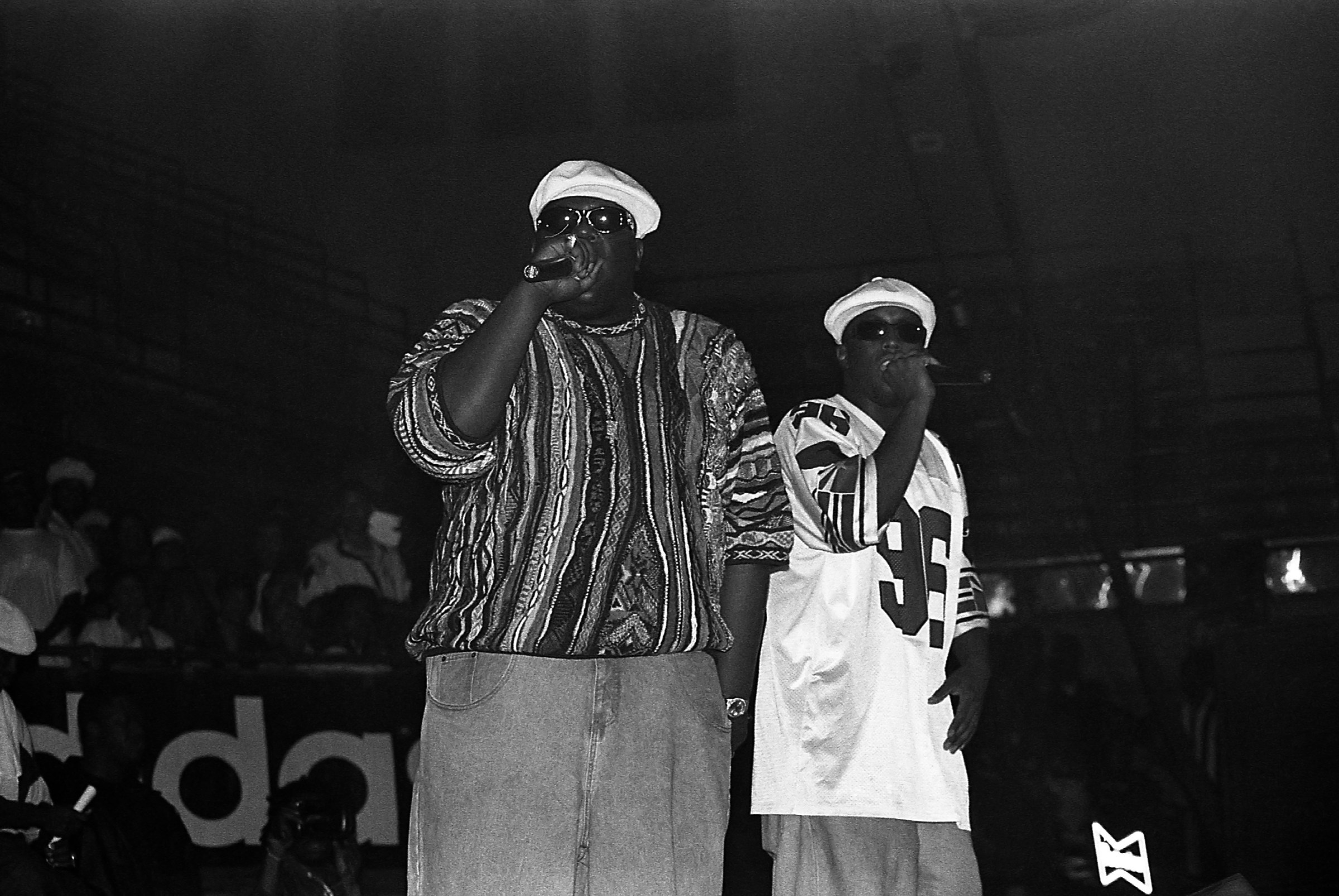

By 1993, Combs had established his own label with the help of Clive Davis called Bad Boy Records, and his reputation as a hungry — and exploitative — executive was cementing. He recruited Bronx rapper Craig Mack and Uptown signee The Notorious B.I.G. (otherwise known as Biggie Smalls, or Christopher Wallace). It was Mack who put Bad Boy on the map with his 1994 hit “Flava In Ya Ear.” However, Combs quickly neglected Mack, focusing his promotional efforts on Smalls. In what was viewed as a controversial and cruel move, Bad Boy released Smalls’s Ready To Die just a week after Mack’s debut album Project: Funk da World, overshadowing his grand introduction onto the scene. Despite Combs’s promise of a second Mack record, Mack left the label in 1996 with one album under his belt.

Combs continued to round out Bad Boy’s all-star roster throughout the mid-’90s, adding the girl group Total, the all-male group 112, powerhouse vocalist Faith Evans, rapper Mase, and the Yonkers trio The Lox. As a hit factory, Bad Boy stood out sonically. Combs and his production team, The Hitmen, were masters at blending rap with R&B hooks and splashy samples, creating the sound largely associated with ’90s cool. In its first three years, Bad Boy had made $75 million in album sales. Still, it was questionable how much Bad Boy’s artists benefited from these gains. Multiple Bad Boy signees, including rapper Mark Curry and The Lox member Lil Cease, have claimed that Smalls was forced by Diddy into signing a bad contract and was broke throughout his mainstream success.

Whatever Smalls actually earned, this did not stop Combs’s marketing Bad Boy and its artists as symbols of luxury and aspirational living for struggling Black youth. Along with B.I.G., Combs had cribbed the “ghetto fabulous” ethos Harrell applied at Uptown Records. In a New Yorker interview with Harrell, journalist Danyel Smith describes the “ghetto fabulous” lifestyle as “buying your way up and out” of a lower-class economic status “even if, mentally or physically, you still live there.”

Combs made his penchant for luxury outwardly known — big chains, mink coats, monochromatic suits. He was also known for making average nightclubs feel exclusive, further popularizing the roped-off VIP section. The tough, gangsta image that defined late ’80s and early ’90s hip-hop had now been sanded down into something more aspirational and decidedly capitalist. In an oral history for GQ, Janelle Monae, who joined Bad Boy in 2008, said the label “was proof that the American dream was real for young Black artists.”

“They really glitzed up hip-hop, which was pretty removed from the genre’s raw and street roots,” says Alphonse Pierre, a staff writer at Pitchfork. “It would quickly face a lot of backlash for accelerating the commodification of the genre, which was already in motion.”

Indeed, the commercialization of hip-hop was already in full swing in the first half of the ’90s, with rappers proving to be worthy rivals to pop acts on the charts and permeating other areas of pop culture. In the late ’90s, hip-hop would get an even bigger stage following the fatal shootings of Smalls and rival Tupac Shakur. Although both cases remain unsolved, they’re largely attributed to the simmering rivalry between West Coast and East Coast rappers, specifically Bad Boy and Los Angeles’s Death Row Records, where Shakur was signed. In the following years and even now, as beef remains a fulcrum of rap, Pierre says their deaths “weighed on everything.”

“If you read any interview or go back and trace any rap beef of the moment, those tragedies were on [rappers’] minds,” said Pierre. “I don’t think rap would ever go back to ‘normal.’ The fear is baked into the genre to this day.”

Despite whatever personal devastation he may have experienced, the hypervisibility and collective pain of this era of hip-hop ultimately worked to Combs’s advantage. The year of Smalls’s and Shakur’s deaths, Combs was working on his first album as a rapper, under the name Puff Daddy, called No Way Out, which was released in 1997. The first single, “Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down,” featuring Mase became a weeks-long No. 1 hit and a proclamation about the durability of his career post-Biggie. As journalist Shea Serrano wrote, “When Biggie was gunned down, most assumed Puff’s career was going to shrivel up and die right along with him.” The assumption would ring false, as No Way Out debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200. A Rolling Stone cover story that year declared him “the new king of hip-hop.”

For obvious reasons, Combs’s tribute to Smalls, “I’ll Be Missing You” featuring the rapper’s estranged wife Faith Evans, became the album’s signature single. Additionally, his performance of the song at the 1997 Video Music Awards marked the most profound moment in his career at that point. Joined by Evans, Mase, 112, and The Police frontman Sting, whose song “Every Breath You Take” is heavily sampled on the track, Combs moved an auditorium of musicians and celebrities to their feet for a unified moment of mourning and hope for a more positive future for hip-hop. Combs was more than just a symbol of a prickly genre; he had become a trusted ambassador.

One of Combs’s first orders of business was his highly exclusive White Parties, initiated in 1998. Combs described the annual bash as an effort to break down “racial” and “generation” barriers. As Amy Dubois Barnett wrote in The Hollywood Reporter, “Not only did the White Parties open up the previously unwelcoming Hamptons for hip-hop and Black people, they made the Hamptons cool for everyone.” Likewise, he blended the stereotypically stuffy, white East Hamptons crowd that included Martha Stewart and Anna Wintour, Hollywood hotshots like Ashton Kutcher and Leonardo DiCaprio, and Black celebrities and video vixens, creating a welcome cultural exchange. White stars could brag about their proximity to an undeniably cool Black mogul — as they often did— while Combs proved his ability to transcend the Hollywood-imposed limits of Black celebrity.

In hindsight, clips of guests and Combs himself discussing his parties are, indeed, damning and unsettling to watch. Following Combs’s federal indictment, a video of Kutcher, who co-hosted the last White Party in 2009, refraining from sharing details about the event on an episode of Hot Ones has raised questions about the possibly criminal acts Combs’s guests may have witnessed over the years.

Despite his illustrious White Parties, the late ’90s and early aughts presented several challenges for Combs. In 1999, Combs and two associates were arrested for beating music executive Steve Stoute at Interscope Records with a telephone and a champagne bottle. (Combs paid Stoute a fine and took a one-day anger-management course.) Later that year, Combs was involved in a shooting incident at a Manhattan nightclub he attended with his then-girlfriend Jennifer Lopez and Bad Boy artist Shyne Barrow. He was arrested and charged with gun possession and attempting to bribe his driver into taking the fall for him.

The trial in 2001 was its own media spectacle, with the verdict broadcast on live television. In what became another shocking tale of luck, Combs was ultimately acquitted on all charges. Meanwhile, Barrow, who claims he was set up by Diddy, spent nine years in prison for gun possession before being deported to his home country of Belize.

With the weight of public scrutiny, Diddy made another identity shift from Puff Daddy to “P. Diddy,” a name that Wallace had given him, in 2001. It was just one of many attempts to shake off his hard-core kingpin image. He focused on his fashion label Sean John and entered the movie business, co-starring in films Monster’s Ball and Carlito’s Way: Rise to Power. In 2004, he founded the political organization Citizen Change, most known for its Vote or Die! campaign.

His relationship with MTV in the 2000s also proved to be a fruitful avenue. On his hit reality show Making The Band 2, he gave the world an inside glimpse into his role as a businessman, as he selected and trained new artists for Bad Boy. As Sheridan Singleton wrote for Collider, the series was an “exercise in masochism,” with Combs often pushing the show’s hungry musicians to sadistic limits. In the series’ most controversial moment, he makes several trainees walk almost five miles to get him a piece of cheesecake from the restaurant Junior’s, barring them from using a taxi or public transportation. These antics only cemented his power as an intimidating, macho figure and added to the shock value of the show. Recent lawsuits against Combs allege that Combs sexually assaulted two minors during auditions for the show, which his representatives have denied.

In the 2010s, Combs dropped the P in P. Diddy, signaling another era of reinvention and unrivaled success. He formed a trio with Danity Kane member Dawn Richard and singer Kalenna Harper known as Diddy – Dirty Money and released the well-performing and critically lauded album Last Train to Paris. In 2014, Forbes named Combs the wealthiest hip-hop mogul, with an estimated net worth of $820 million, in part due to his successful partnership with the vodka brand Ciroc and his purchase of DeLeón Tequila.

By the mid-2010s, Combs was fully reveling in his role as an elder statesman of rap. A star-studded tribute to Bad Boy Records at the 2015 BET Awards and subsequent reunion tour brought more attention to his cultural contributions. From then on, reminders of Combs’s impact on the music industry never really stopped: In 2022, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the BET Awards. He received the Global Icon Award at the 2023 Video Music Awards. That same month, New York City Mayor Eric Adams gave him the key to the city.

In one of his last profiles before the ongoing legal saga, Diddy reflected on the impact of success and how he planned to utilize all the power he had accumulated in the service of others. “It clicked in and went from me to we,” he told Vanity Fair. “I was sent here not to just do those things that are kind of rooted in personal success.” Combs would go on to throw some of his money at good causes and reassign publishing rights to some of Bad Boy’s artists. But for many of his critics, his legacy as a self-promoting billionaire had already been cemented. There were the decades of damage Combs has caused to his artists and others but, more broadly, the harmful ways he influenced hip-hop as a culture.

Jared Ball, author of The Myth and Propaganda of Black Buying Power, says that Combs “represented the increasing success of the corporate world to colonize the already-colonized Black community.”

“When hip-hop emerged, it had everything,” Ball says. “You had some radical and Black nationalist messages. But he was able to take advantage of a broader desire to politically weaken and undermine this emerging cultural expression. He oversaw the rise of the most material and capitalist form of the art.”

Combs was like many Black entrepreneurs who frame their material success as revolutionary while preaching about Black excellence. These statements have long been called into question, according to Ball. However, in wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, hip-hop fans on social media have taken these billionaires to task for their capitalist-driven approaches to activism and questionable ways of earning their wealth.

Jay-Z and Beyoncé have received large amounts of criticism over the past decade for advocating for personal wealth as a route to Black liberation. Pharrell Williams is another Black music mogul who’s been accused of signing young artists into bad deals and stealing money from colleagues, although his representatives pushed back on the latter characterization. Despite all of this, they’re still widely celebrated as businessmen and showered with awards and tributes for their impact on the Black community.

This tendency to uplift wealthy Black moguls continues to shield these men (and the occasional woman) from accountability, particularly when they’re exposed for harming women. Another hip-hop mogul, Dr. Dre — who has a well-recorded history of allegations of physical abuse against Black women — had a lifetime achievement award named after him at the Grammys just last year. Despite a slew of sexual misconduct allegations and lawsuits that emerged during the #MeToo movement, Russell Simmons has maintained relationships with Black media, including — maybe not ironically — Revolt TV, formerly owned by Combs. Needless to say, it was a gross amount of wealth that afforded Combs the ability to allegedly run an extensive criminal enterprise and coerce his accusers into silence for decades.

With these grim circumstances in mind, it’s not surprising Combs’s behavior was hip-hop’s best-kept secret for so long. It turns out his true dilemma was never a matter of anyone holding him down, but the industry allowing him to carry on.