A month ago, the genre-bending electronic musician FKA Twigs testified before the US Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, urging policymakers to protect artists from being exploited by AI, whether from using their voice to generate songs, copying their likeness to create pornography, or scraping their body of work for training data.

Watching a C-SPAN2 video of a buttoned-up woman who, in my mind, is usually a goddess plummeting down a pole into a golden-red underworld was fascinating. Senators watched silently as Twigs, legal name Tahliah Debrett Barnett, told them, “My art is the canvas on which I paint my identity and the sustaining foundation of my livelihood.” Generative AI, she said, “threatens to rewrite and unravel the fabric of my very existence.”

FKA Twigs is not the first artist to express fear, anger, and a sense of urgency about the nonconsensual use of her digital likeness. At the beginning of April, over 200 musicians signed an open letter issued by the Artist Rights Alliance calling on AI developers, tech companies, and music services to pledge not to undermine or replace human artistry.

Then OpenAI released a flirty, openly Her-inspired voice assistant named Sky that sounded suspiciously like Scarlett Johansson — and rushed to take it down after Johansson objected. The debacle demonstrated just how fuzzy the boundaries of intellectual property can be, especially when it comes to someone’s voice and likeness. (Disclosure: Vox Media is one of several publishers that have signed partnership agreements with OpenAI. Our reporting remains editorially independent.)

My unofficial assessment of the vibe surrounding celebrities and generative AI: bad.

… But what if you are a celebrity, working with your own clone?

After condemning the use of AI to misappropriate artists’ identities, FKA Twigs told senators that she spent the past year training a deepfake of herself, which can emulate her personality and tone of voice across multiple languages. “I will be engaging my AI Twigs later this year to extend my reach and handle my online social media interactions,” she said, “whilst I continue to focus on my art from the comfort and solace of my studio.”

“AI Twigs” wasn’t much more than a side note in the context of last month’s hearing, but I haven’t stopped thinking about her. What would it mean if artists could harness the power of generative AI to offload grunt work — content creation, press junkets, self-promotion — to their digital clones, leaving the human originals free to invest wholeheartedly in their creativity?

The difference between OpenAI’s Sky and AI Twigs “is the idea of consent,” Sarah Barrington, an engineer, AI researcher, and deepfake detection expert at the UC Berkeley School of Information, told me. Twigs gave consent, while Johansson did not.

But even with enthusiastic consent, Barrington suspects that maintaining total control over one’s digital likeness is nearly impossible. The question then becomes whether the marketing demands of the music industry are burdensome enough that it’s worth putting a deepfake of yourself out there.

Can deepfakes save artists from TikTok? (Probably not.)

Being an artist today is not what it used to be.

Musicians, authors, and visual artists can no longer scrape by with talent, hard work, and good looks alone. We’re living in the “personal brand” era, where most artists have to strategically craft a vulnerable, cool, and, most of all, consistent social media presence to get signed to a label.

The relentless self-marketing is time-consuming at best and soul-crushing at worst. No matter how many “POV: you found your new favorite indie band” videos a musician makes, earning a living through streaming and touring alone remains more challenging than ever.

Even when TikTok virality launches a band toward a record deal, the demand for content creation is constant, making it next to impossible for artists to simply make art. It can take hours to keep up with trends, plan bits, film, and cobble video clips together. Even with a social media manager, the pressures of content creation clutter valuable brain space and twist every event into an opportunity for filming B-roll.

Outside of my job here at Vox, I play bass in a San Francisco-based indie band. Music is a great love of mine, but it’s my bandmate’s driving purpose and full-time job. He regularly posts self-promotional TikTok videos on behalf of the band, just like all of my favorite local artists desperately trying to grow an audience.

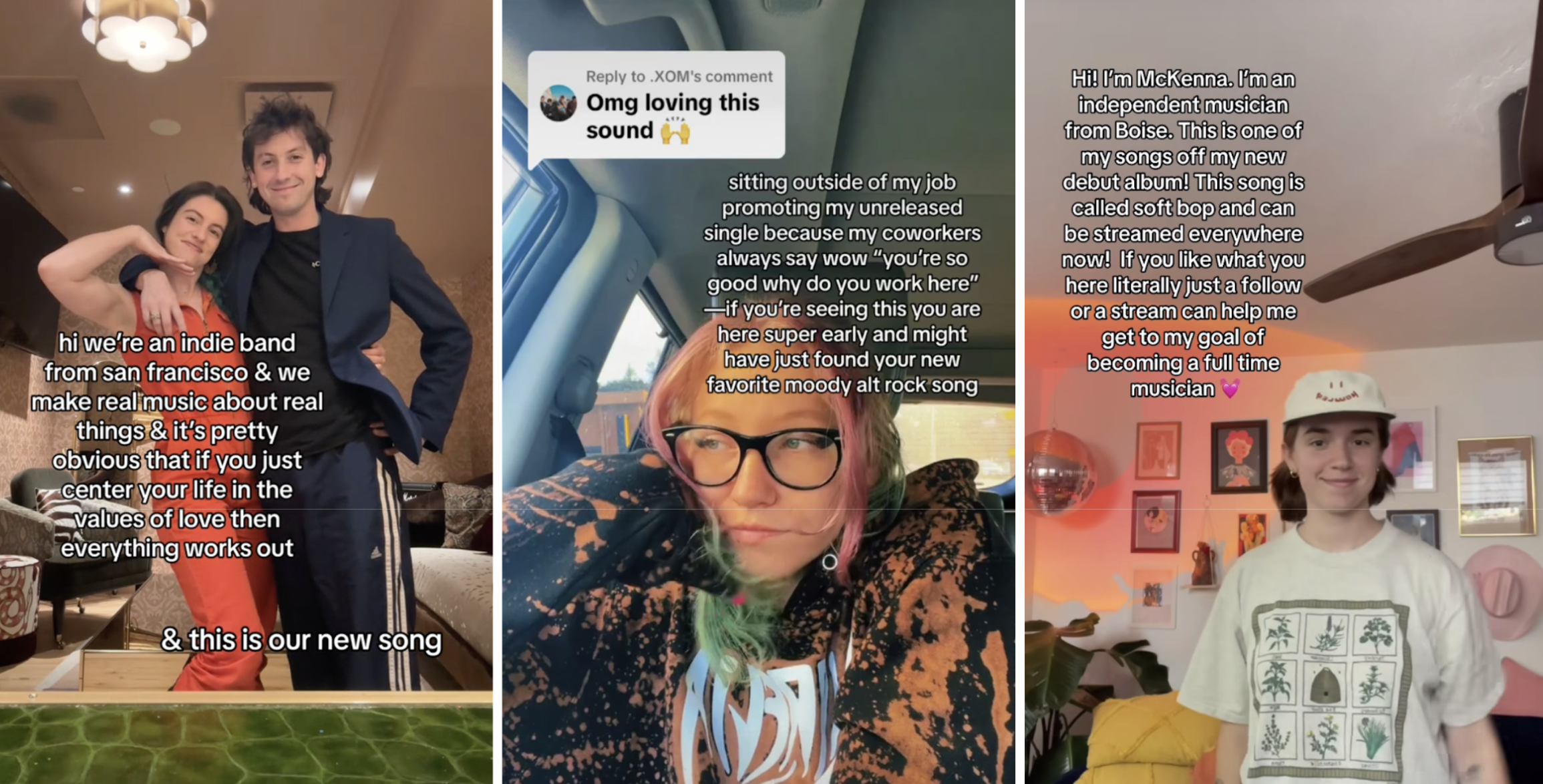

Screenshots exemplifying self-promotional indie band content. These artists, and many like them, post videos like this nearly every day. From left to right: Analog Dog (ft. Celia on the left, Instagram @analogdogband, TikTok @analogdog), Britta Raci (@brittaraci on Instagram and TikTok), and McKenna Esteb (@mckennaesteb on Instagram and TikTok). @analogdog, @brittaraci, @mckennaesteb

When I heard about AI Twigs, my mind immediately went to the countless musicians cranking videos out for the void. If all of them could employ deepfakes to do this labor on their behalf, they could put their phones down and write better music. We spend a lot of time talking about how deepfakes can go wrong. AI Twigs got me wondering whether maybe, with strong enough guardrails, they could possibly go right.

Purposefully using generative AI to broaden one’s reach isn’t unheard of. Shamaine Daniels, a Democratic candidate who ran in the primary for US House Pennsylvania District 10, used a generative AI phone banker named Ashley to reach voters leading up to an election this April. Unlike a human phone banker, Ashley could have thousands of simultaneous one-on-one conversations with voters in their primary language, without getting flustered or frustrated. While Ashley was far more personalized and interactive than your everyday robocall, she isn’t a deepfake. Civox, the company behind the bot, made Ashley sound robotic enough that voters wouldn’t confuse the voice for a real human.

They didn’t have to do this — no federal laws directly regulate what companies like Civox are doing. As Twigs said in her testimony, AI-powered tools aren’t necessarily a problem, but stealing and exploiting a musician’s likeness without their consent very much is. Without proper regulation, the line between “good” and “bad” applications of AI is hazy.

The question remains: Can deepfakes actually save artists from TikTok and the ceaseless demand for content creation?

It’s possible that generative AI could be used to create personalized content for fans, which, if done right, could be engaging without feeling shady. Fans increasingly demand authenticity from the musicians and influencers they follow, but the fact that most major artists are not actually making their own social media content is a wide-open secret. Maybe it’s just the feeling of intimacy we crave — authenticity is optional. AI Twigs, for example, could post Close Friends Instagram stories in the primary languages of every fan. (Billie Eilish briefly added everyone to her Close Friends story leading up to her latest album release and gained 10 million new followers — people love it.)

Unfortunately, it’s unlikely that the pros will outweigh the cons. Barrington told me that right now, applications of deepfakes are about 95 percent bad and 5 percent good. Beyond nonconsensual pornography and identity fraud, “there’s the fundamental erosion of democracy by creating disinformation.” While AI Twigs presents an interesting positive use case, Barrington fears “it only adds about 1 percent to that 5 percent good.”

You can make your own deepfake — but so can everyone else

While some states have passed legislation addressing nonconsensual deepfakes, and several bipartisan acts addressing pornographic forged images and digital replicas in art have been introduced at the federal level, there are effectively no laws in place to stop anyone from using generative AI to do whatever they want.

Let’s say AI Twigs goes live on Instagram. Confirming that content featuring AI Twigs came from some official FKA Twigs source, like her verified Instagram account, would be pretty straightforward. But it would be very hard to stop others from making knockoff Twigs.

“I could probably do it in a day,” Barrington told me. Even someone without Barrington’s computer science know-how could figure it out relatively quickly with a few bucks and some YouTube tutorials. While an artist like FKA Twigs could be down to see their digital clone online, so long as they maintain sole ownership of it, “I don’t know how she would enforce this in reality,” Barrington said.

At least visual deepfakes — especially if they portray the original person doing something extremely shocking or unlike their usual self — tend to land somewhere in the uncanny valley, so it’s still possible to spot them if you know what to look for. Meanwhile, high-quality synthetic voices are already indistinguishable from real ones, unless you have sophisticated detection tools (and Barrington said even those don’t always work).

In any case, as we learned from last month’s ScarJo fiasco, it’s hard to claim total ownership over one’s voice, no matter how distinctive.

Detection technology won’t be able to outpace the potential harms of deepfakes. “There will never be a silver bullet to detecting with 100 percent accuracy whether something is fake or not,” Barrington told me, “and you can never truly prove something is real.”

AI generated media is here to stay, but FKA Twigs may be racing too far ahead of the curve. Embracing generative AI as an artist feels a bit like making a deal with the devil: You can stop making promotional one-liners, but you might wind up in porn or an AI-produced song without your consent.

Legal battles around the use of generative AI will likely inspire more regulation in the near future. But in the legal gray zone we’re currently dealing with, AI Twigs likely presents more problems than she solves.

A version of this story was initially published in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here to subscribe!

![ROSE IN DA HOUSE I BE MY BOYFRIENDS 2 [OFFICIAL TRAILER]](https://cherumbu.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/ROSE-IN-DA-HOUSE-I-BE-MY-BOYFRIENDS-2-OFFICIAL-150x150.jpg)