May 1, 2024:

Even borrowing money is more expensive these days — and the Federal Reserve might decide to keep it that way for a while.

All eyes are on the Fed’s May meeting today, where Fed chair Jerome Powell will make an announcement about interest rates. Though analysts do not expect the Fed to cut rates just yet, some had projected a cut might be coming soon. That now appears increasingly unlikely.

Instead, his remarks are expected to shed light on how much longer the US economy will have to endure high interest rates, which are squeezing everyone from prospective home buyers to people who have racked up credit card debt.

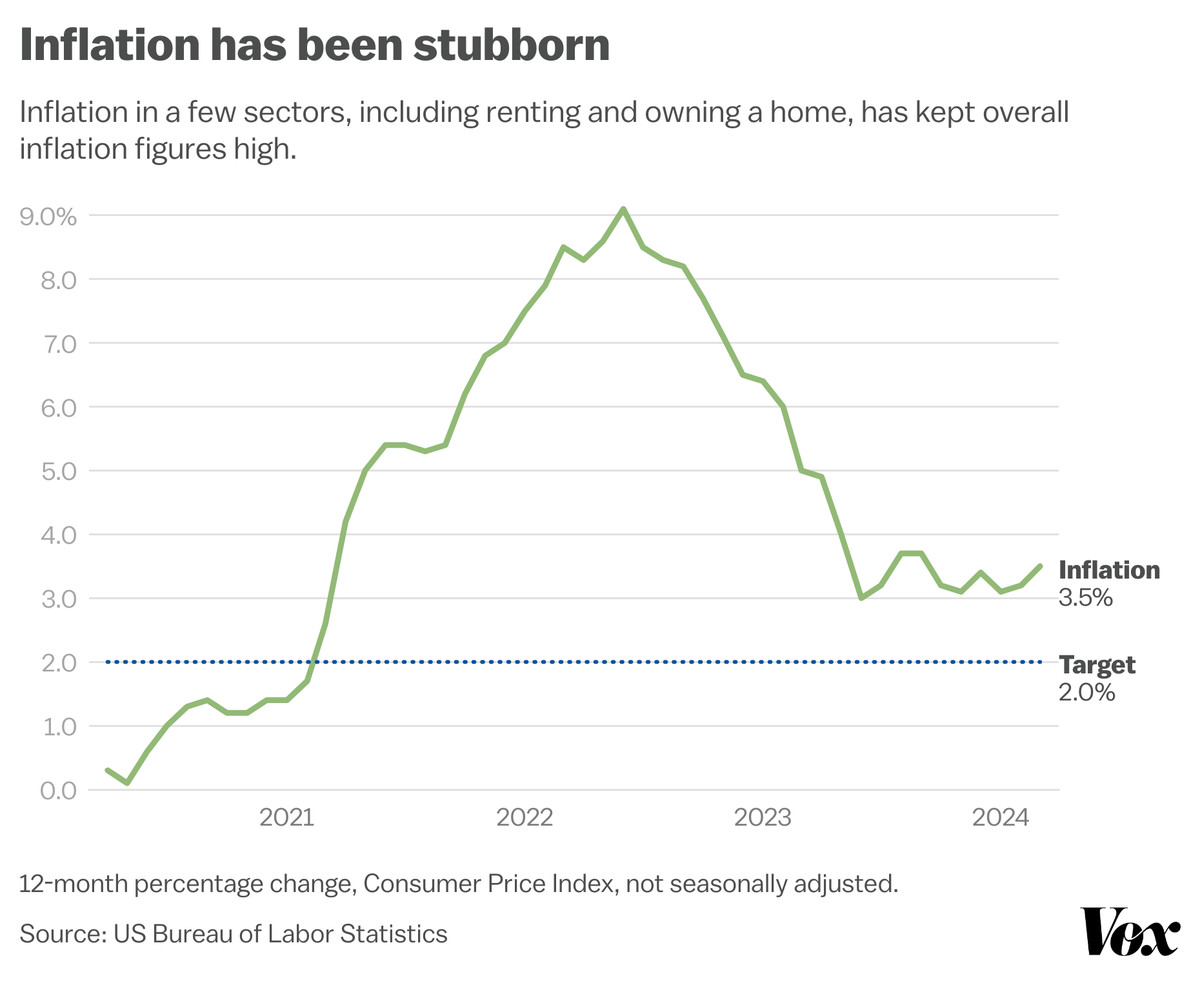

High interest rates have helped cool a too-hot economy, significantly bringing down inflation to 3.5 percent from its 9.1 percent peak in June 2022. But it’s still well above the Fed’s target rate of 2 percent, and inflation has increased slightly in the last few months, which means we might not see a rate cut anytime soon.

“The ‘last mile’ … to the Fed’s target range was expected to be more difficult than what came before it,” said Matt Colyar, an economist at Moody’s Analytics. “Even with that expectation, however, inflation data in the first three months of 2024 has been surprisingly high.”

A few factors are driving stubborn inflation.

Housing costs have been the biggest contributor by far. Inflation in rent and homeowners’ cost of living in their own homes has moderated somewhat but by less than expected, Colyar said. Auto insurance and repair costs have also risen sharply even though car prices have fallen. And health care costs have also picked up.

Nicole Narea/Vox

But this isn’t necessarily a “strong indication that inflation will remain similarly high for the rest of 2024,” Preston Caldwell, chief US economist at Morningstar, said in a note to investors Friday.

The US economy has so far staved off a recession, growing at a slower but still solid pace in the first quarter of 2024 in part because Americans are continuing to spend a lot. The job market also remains strong, with the US blowing past projections to add 303,000 jobs in March.

That hasn’t given the Fed much urgency to cut rates anytime soon. “It’s not an economy in obvious need of the pick-me-up that a rate cut would deliver,” Colyar said.

Strong consumer spending, though, isn’t expected to last as Americans deplete any savings they accrued in the pandemic and rack up more household debt. That will likely cause US economic growth to slow in the coming year, which “should be sufficient to cool off remaining excess inflation,” Caldwell told Vox.

After the Fed’s December meeting, financial analysts were expecting six interest rate cuts in 2024, beginning in June. But given that inflation has remained high and the economy is still going strong, that doesn’t seem to be happening anytime soon.

Caldwell said he’s now expecting three cuts this year starting in September. Other top economists at UBS, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America have also pushed back their projections for a rate cut. For example, Bank of America is projecting only a single rate cut in December.

Some Fed officials also have not ruled out the possibility of another rate hike, which would be the first since last July. Fed Governor Michelle Bowman recently said she would support a rate hike “should progress on inflation stall or even reverse.”

But Caldwell said that still seems a far-off possibility. “The mere fact that they’re delaying rate cuts already has a contractionary effect on the economy,” he said.

Colyar said he will be watching Powell’s remarks to discern “how spooked they have been by the hotter-than-expected inflation data in the first quarter” and to what extent he attributes the stickiness of inflation to a few industries, rather than an indication of current overall cost pressures.

Recent economic data has already dampened earlier enthusiasm in the stock market about an imminent interest rate cut. Powell’s remarks might have a similar depressive effect, depending on how pessimistic he is about the Fed winning its battle against inflation in the near term.

“The first effect is psychological,” Colyar said. “Persistently high borrowing costs are painful and will eventually break something.”

It’s already slowing down the real estate market significantly. Mortgage rates have surpassed 7 percent, and that’s keeping prospective home buyers and sellers on the bench. People who secured lower interest rates just a few years ago don’t want to sell and would have to secure a higher-rate mortgage for their new lodging, so there are fewer homes on the market, keeping prices higher than many buyers can afford.

Americans’ total credit card debt also hit a record $1.13 trillion earlier this year, and repaying that in a high interest rate environment is bound to hurt their wallets.

At the same time, the US economy has proved resilient even in a high interest rate environment. The Fed doesn’t need to step in just yet given steady job growth and economic growth, as well as strong consumer spending.

“However, I would argue that the time to start loosening policy is before things are flashing red,” Colyar said. “Waiting too long because shelter prices are slow in moderating I think is an unnecessary risk.”

This story appeared originally in Today, Explained, Vox’s flagship daily newsletter. Sign up here for future editions.