This Sunday, French voters will cast their ballots in the first round of the country’s parliamentary election — one that President Emmanuel Macron called as a surprise after the far-right National Rally (RN) won big in the European parliamentary elections earlier this month. The French polls suggest that the RN will also win big on Sunday and in the second round of voting that follows a week later — gaining either a plurality of seats or perhaps even an outright majority.

While the final results may not be known for more than a week, the stakes are quite clear and quite high. In the French system, presidents depend on parliamentary majorities for major domestic policy-making; without a majority, Macron will be fairly impotent at home. If the RN has an outright majority, it can start passing parts of its far-right agenda, and Macron will have only limited tools to stop them.

On one level, this isn’t surprising. The RN’s long-time leader, Marine Le Pen, has been Macron’s chief rival in the past two presidential elections. It’s clear that her party has emerged as the leading alternative to Macron’s centrism; few observers are surprised that his decision to call this parliamentary election early is likely to lead to RN gains. A deeply unpopular president causing voters to turn to the opposition: In some ways this is just democracy as usual.

But on another level, the RN’s rise should be truly shocking.

Not so long ago, the party’s extremism made it anathema to nearly everyone in France. When Le Pen’s father and the party’s founder Jean-Marie made it to the second round of the presidential election in 2002, nearly the entire country rallied against him and his party (then called the National Front, or FN). He lost in a landslide 82–18 defeat, the worst showing of any presidential candidate since 1958.

Even after years of Marine Le Pen softening the RN’s image, its policy agenda remains nearly as radical as it was then. The RN’s signature policy is to enact a “national priority” law formally discriminating against immigrants in housing, hiring, and public benefits.

The real story of the 2024 election is not that voters are turning against Macron, but how the far right came to be seen as a palatable alternative.

It’s a rise fueled in large part by the RN’s canny political strategy, an extreme party doing a brilliant job of making itself seem reasonable to voters outside its base. But it’s also been fueled by the hubris and missteps of Macron, who seems motivated by a false sense that the RN was so toxic that he would inevitably triumph in a forced binary choice, just as his predecessor did in 2002.

These two forces have worked in tandem to turn the RN into the de facto leader of the opposition to an unpopular president. And now, France — like other democracies around the world — is reaping the whirlwind.

How France’s extreme right mainstreamed itself

The rise of the RN can best be understood as a kind of double normalization, with each generation of Le Pens playing a distinct but crucial role.

After World War II, the European far right appeared to be a spent force. No political movement could hope to win national elections promising a Third Reich redux; those that tried found no success.

French politics immediately after the war — the Fourth Republic period — was tumultuous. After a military revolt in 1958, World War II hero Charles de Gaulle took power and ushered in a new constitution. The Fifth Republic remains the system under which France operates today. After De Gaulle left power in 1969, French elections evolved into relatively stable contests between center-right and center-left blocs.

Jean-Marie Le Pen was the first to develop a credible far-right alternative.

Recognizing that the Nazis had rendered dictatorship and race hatred beyond the pale, Le Pen refocused the far right on contesting elections by attacking immigration. The argument wasn’t (primarily) that minorities were biologically inferior, just that France is under no obligation to admit culturally distinct foreigners and treat them as equals. After he founded the National Front for French Unity (FN) in 1972, the party adopted the slogan “France is for the French.”

Le Pen paired this xenophobia with extreme nationalism. He was a veteran of France’s failed wars to keep colonies in Vietnam and Algeria; in one contemporary interview, he seemingly confessed to personally torturing Algerian detainees (a charge he later denied). As a politician, Le Pen defended French imperialism and railed against its diminished glory in a post-colonial era. Immigration, for Le Pen, was a kind of “reverse colonization” in which France’s former subjects were destroying its identity from within.

Because the FN was never an outright fascist party, it could put itself forward as something distinct from Europe’s discredited Hitlerite past. This “reputational shield,” as scholars term it, helped it make inroads into French politics in ways that neo-Nazis never could. In 1984, just 12 years after its founding, the FN managed to win 11 percent of the national vote in a European Parliament election. It soon became a model for far-right parties across the continent, which rapidly began outperforming neo-Nazi rivals.

Nonetheless, the FN had a clear ceiling, and Le Pen himself was a big part of the problem. The party’s founder has always had a habit of rhetorical bomb-throwing that kept it from making further inroads with the broader public.

He has repeatedly engaged in Nazi apologia, calling the Holocaust a “detail” of history and saying that “in France, at least, the German occupation was not particularly inhuman.” In a 2006 interview, he said that “you can’t dispute the inequality of the races” because “blacks are much better than whites at running, but whites are better at swimming.” In his 2018 memoir, he defended French citizens who volunteered for the German SS during World War II.

“I — like millions of other French people — grew up with the image of Le Pen as a snarling bigot with an underbite, a political bogeyman who tidily gathered up all the ugliness of France’s recent history,” journalist Nick Vinocur writes in Politico.

When Jean-Marie’s daughter Marine took over the FN in 2011, she was initially perceived in much the same way. But the younger Le Pen proved a cannier operator, not only realizing that her party needed an image makeover but successfully delivering on it.

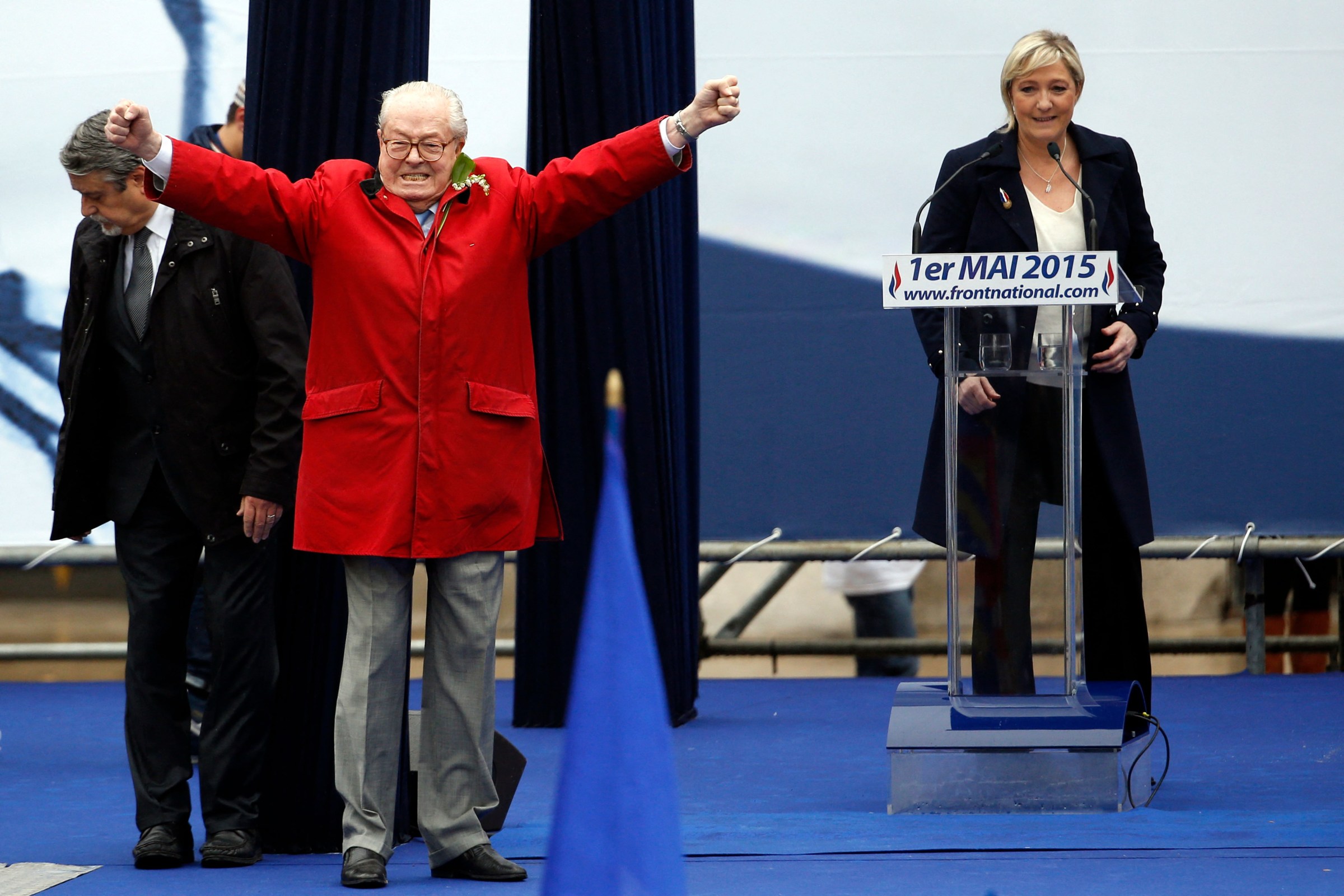

France’s far-right political party Front National founder and honorary president Jean-Marie Le Pen gestures onstage as FN’s president Marine Le Pen looks on, in Paris France, May 1, 2015.Kenzo Tribouillard/AFP via Getty Images

Much of this was about language. As Vinocur reports, she shifted the party’s demagoguery away from direct attacks on Muslims and Arabs and toward dog-whistles about cultural change and terrorism.

She would occasionally discipline party members who crossed her lines — including, most notably, her father. In 2015, when Jean-Marie once again got into trouble over comments about Jews and the Holocaust, Le Pen did the unthinkable: She expelled her father from the party he founded. He should “no longer be able to speak in the name of the National Front,” she said at the time.

In 2018, following a decisive presidential defeat, she changed the party’s name from National Front to National Rally. While seemingly minor, the move helped distance the party from her father’s relatively toxic brand and establish Le Pen’s independence as a political figure.

In the current election, she has tried to elevate candidates — most notably, 28-year-old party leader and proposed prime minister Jordan Bardella — who come across as normal, suit-wearing politicians rather than bombastic confessed torturers.

Don’t be fooled. Experts on French politics say that Le Pen’s moderation is primarily symbolic. While she has sanded off the RN’s rough edges, she also has maintained the far-right policy core — most notably, the “national priority” system mandating discrimination against immigrants in public goods — that helped make her father’s party so toxic in the first place. During the current campaign, Bardella vowed to ban dual nationals from holding government jobs.

“From [a policy lens], there’s very little difference between what Marine Le Pen is running with and what Jean-Marie was defending,” says Marta Lorimer, a Cardiff University expert on French politics.

Together, in short, the Le Pens accomplished one of the most successful political rebrandings in modern history. They created a party rooted in thinly veiled bigotry and, without significant policy compromise, turned it into something that the median French voter might actually consider supporting.

Macron’s (implicit) deal with the devil

The RN’s recent success is not merely a story of Marine Le Pen’s political skills. Like most European far-right parties, it benefited hugely from the 2015 refugee crisis, which turned its signature issue of immigration into the issue across the continent.

Le Pen also benefited from the rise of Emmanuel Macron, a self-proclaimed “radical centrist” who shattered the foundations of France’s party system. In doing so, he created the perfect conditions for Le Pen’s rebranding to succeed.

The traditionally dominant factions of the center right and center left, today called the Republican and Socialist parties, saw themselves as rivals with a shared responsibility: guarding the republic from extremist forces that would harm it. They agreed never to share power with the FN/RN, an agreement referred to as “the republican front” or “cordon sanitaire.”

Macron broke the two-party system. In 2016, he quit his position as finance minister under a Socialist president to run for president at the head of a party he just founded, now called Renaissance. At the time, this may have seemed like an act of extreme hubris. But Macron proved far more popular than either of his mainstream rivals, and he won the most voters in the first round of France’s 2017 election. He faced Marine Le Pen in the head-to-head second round and crushed her.

After winning power, Macron made two moves that would serve his short-term political interests but end up paving the way for the RN’s rise in the long run.

First, Macron built his new party as a kind of centrist empire, one designed to occupy the entirety of the territory between radical right and extreme left. Containing both former Socialists and Republicans, its rise sapped the vitality from the already-weakened established parties.

Their decline should, in theory, have left Macron and Renaissance the only serious choice for most French voters. Certainly that was Macron’s theory.

No politician, even one as “Jupiterian” as Macron, can maintain a personal majority forever. Macron has become deeply unpopular, with a mere 26 percent of French voters approving of his current performance. It’s easy to blame specific policies, like his pension reform and failed gas tax, but it also might be plain old exhaustion. Around the world, incumbents are unpopular, and Macron has been in office for seven years.

So if French voters want to vote against Macron, who should they turn to? The center right is a shadow of itself. The center left has been forced into an unwieldy “new popular front” alliance with the polarizing and unstable extreme left, led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon. There’s a smaller extreme-right party, led by comedian Eric Zemmour, but he’s even more radical than Le Pen.

That leaves only one non-Macron option with a proven electoral track record: the RN.

“There’s only two options for voters,” says Florence Faucher, a professor of political science at France’s Sciences Po research center. “At some point, people are going to want change from the majority of Macron.”

But Macron didn’t just demolish the other centrist parties. He actually aided Le Pen’s strategy of normalizing her party by tacking to the right on immigration. “It’s not so much that the National Rally has moderated [on immigration] than that the entire political system has radicalized,” says Lorimer.

French President Emmanuel Macron at a press conference after the end of the two-day European Council and Euro Summit in Brussels, Belgium, on October 27, 2023.Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Macron has, for example, said that “Islam is a religion that is in crisis all over the world” and banned some traditional Muslim clothing in schools. (Roughly 6 million people in France practice Islam or come from a Muslim background.) Last year, he had Parliament pass an immigration bill so draconian that Le Pen hailed it as “an ideological victory” for her party.

She was more correct than it seems. Some research on European politics suggests that when parties in the center take right-wing positions, they don’t actually win over that party’s supporters. Instead, they end up normalizing far-right discourse on the topic: helping people on the fence think it must not be so weird to rail against Islam if self-proclaimed centrists are doing it and that maybe they can consider voting for the far right without being a bad person.

That appears to be how Macron’s strategy has worked out in France. His attempt to take out Le Pen’s signature issue has only made her seem more reasonable, all without persuading her base to defect to the center.

“All the attempts to co-opt the far right have aided the process of normalization,” says Art Goldhammer, an expert on France at Harvard University’s Center for European Studies. “The slogan in France is that people prefer the original to the copy.”

It wasn’t Macron’s intent to usher in an RN-led Parliament. His actions betray a belief that the RN would always have a ceiling; that, when push comes to shove, the French people would always choose his moderation over Le Pen’s extremism when presented with a binary choice.

This strategy has long worked in modern France, but Macron appears to have finally found its limits. The same arrogance that powered Macron’s 2017 presidential bid has now brought France to the brink of a Parliament dominated by radicals.