April 17, 2024:

Experts and whistleblowers testified before Congress today. The upshot? “It was all about money.”

Boeing went under the magnifying glass at not one, but two Senate hearings today examining allegations of deep-seated safety issues plaguing the once-revered plane manufacturer. Witnesses, including two whistleblowers, painted a disturbing picture of a company that cut corners, ignored problems, and threatened employees who spoke up.

These hearings have convened just four months after a door plug blew out of a Boeing-made Alaska Airlines plane mid-flight in January, sparking further concerns about a precipitous downslide in Boeing’s reputation for safety and quality in recent years. The first hearing, held by the Senate Commerce Committee, questioned aviation experts who put together an FAA report published in February. It concluded that the company had not made enough strides in improving its safety culture since the deadly 2018 and 2019 737 MAX crashes that killed 346 people.

“There exists a disconnect, for lack of a better word, between the words that are being said by Boeing management and what is being seen and experienced by employees across the company,” said witness Javier de Luis, an aerospace engineer and lecturer at MIT.

The FAA report conducted hundreds of interviews with Boeing employees across the country, and the authors found staff often didn’t know how to report concerns or who to report them to. “In one of the surveys that we saw, 95 percent of the people who responded to the survey did not know who the chief of safety was,” said Tracy Dillinger, manager for safety culture and human factors at NASA.

The second hearing put the spotlight on two whistleblowers — Boeing quality engineer Sam Salehpour and former Boeing engineer Ed Pierson — alongside aviation safety advocate and former FAA engineer Joe Jacobsen and Ohio State University aviation professor Shawn Pruchnicki. The whistleblowers slammed Boeing for allegedly knowing about defective parts and other serious assembly problems, and choosing to ignore or even conceal them. Such problems could slow down production and be expensive to fix — and internal and external critics say that Boeing’s priority was maximizing its profits.

Salehpour said he had gone up high in the chain of command at Boeing to alert them of his concerns, having written “many memos, time after time.” Yet he says his warnings went unheeded — and he was punished for bringing them up.

“I was sidelined. I was told to shut up. I received physical threats,” he said. “My boss said, ‘I would have killed someone who said what you said in the meeting.’”

During Wednesday’s hearings, witnesses reiterated that Boeing management had been overly focused on ramping up production while also cutting costs.

Salehpour, who has worked at Boeing since 2007, came forward in early April warning that more than 1,000 Boeing planes in the skies were in danger of structural failure due to premature fatigue. In the 787 line, tiny gaps between plane parts hadn’t been properly filled, he said. “I found gaps exceeding the specification that were not properly addressed 98.7 percent of the time,” Salehpour testified during the hearing today. He said that debris ended up in these unfilled gaps “80 percent of the time.” Such debris could, in some cases, result in a fire.

On the 777s, he found “severe misalignment” of airplane parts. “I literally saw people jumping on the pieces of the airplane to get them to align,” he said. Salehpour urged Boeing to ground all 787 Dreamliner planes ahead of his testimony. Boeing, for its part, has denied Salehpour’s assertions, saying that “claims about the structural integrity of the 787 are inaccurate” and noting further that it had tested the 787 line many more times than the jet would actually take off or land in its lifespan, and had found no evidence of fatigue.

But Salehpour pointed out today that the above-and-beyond stress testing referred to older 787 planes, in which excessive force wasn’t used during assembly.

Talking about the faulty software system that contributed to the deadly 737 MAX crashes, Pruchnicki, the OSU professor, accused Boeing of sneaking the system through the certification process. “It was all about money,” he said. “That’s why those people died.”

There were plenty of fingers pointed at the FAA for failing to oversee Boeing with a tighter rein. When Sen. Richard Blumenthal asked if hiring more FAA inspectors would help, Jacobsen, the former FAA engineer, answered that it would — but that the attitude needed to change. “The attitude right now is Boeing dictates to the FAA.”

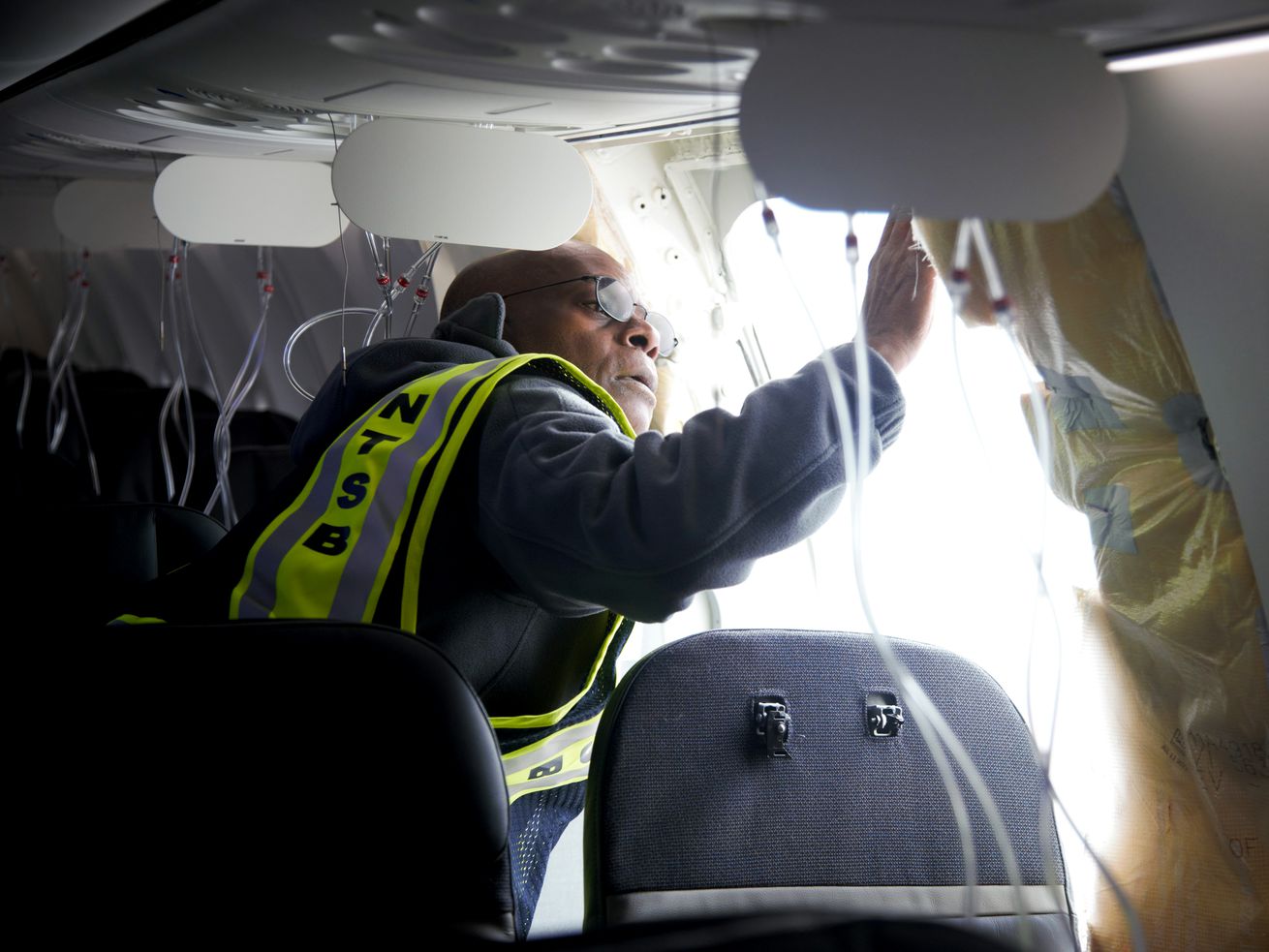

Boeing has said it’s cooperating fully with investigators, but at another Senate hearing in March, the chair of the National Transportation Safety Board testified that, two months after the Alaska Airlines incident, Boeing still had not provided several records related to door plug failure. Boeing says it can’t find them.

Pierson, the ex-Boeing whistleblower, testified today that this couldn’t be true. “I’m not going to sugarcoat this: This is a criminal cover-up,” he said. “Records do in fact exist. I know this because I’ve personally passed them to the FBI.”

A steady crop of whistleblowers have come forward over the decades flagging issues with Boeing’s planes, particularly after the MAX crashes. Boeing’s safety concern tip portal also saw a 500 percent increase in reports after the Alaska Airlines accident.

A previous whistleblower from Boeing’s South Carolina plant, former Boeing quality manager John Barnett, claimed there were numerous quality issues with Boeing’s manufacturing process, including dangerous debris that hadn’t been removed from its jets and issues with its emergency oxygen system. He was recently found dead of an apparent suicide right before his third day of deposition testimony in his whistleblower lawsuit; Barnett, like others, said that he had faced retaliation from the company. Some of Barnett’s former coworkers don’t believe he died by suicide, according to reporting from the American Prospect.

We don’t know yet what the results of the ongoing regulatory and criminal investigations into these recent safety scares will be, or the consequences for Boeing. CEO Dave Calhoun recently announced he would be stepping down from the position at the end of this year. Boeing already underwent a fraud investigation for the earlier 737 MAX crashes — it agreed to pay $2.5 billion to settle the case, avoiding a criminal conviction.

Boeing’s safety issues are especially unsettling because there isn’t a quick fix to untangling them. It’s been more than five years since the deadly 737 MAX disasters, and according to aviation experts and current and former employees, the company hasn’t managed to right the ship.

That critics have accused Boeing of pushing for higher profits at the expense of safety is an alarm bell for anyone who ever plans to take a commercial flight again. There are just two passenger jet makers that dominate the market: Boeing and Airbus. “You’ve got a management team that doesn’t seem terribly concerned with their core business in building aircraft,” Richard Aboulafia, managing director of the consulting firm AeroDynamic Advisory, told Vox in January.

Commercial aviation is remarkably safe, but that near-pristine safety record was hard-earned. It’s understandably shocking that one of the world’s only commercial jet manufacturers appears to have let its once-high standards slacken, if the allegations of Boeing whistleblowers are true. It’s also prudent to expect the highest rigor possible for aviation safety — good enough isn’t good enough. Boeing has consistently downplayed structural problems with its planes and denied that it puts profits over quality. But the number of whistleblowers and experts saying otherwise is reaching a deafening pitch.

“It really scares me, believe me,” Salehpour said of being a whistleblower and facing retaliation. “But I am at peace. If something happens to me, I am at peace, because I feel like, coming forward, I will be saving a lot of lives.”