January 16, 2024:

It has been 30 years since Sherry Molock found her calling: to help prevent suicide among young Black people.

Today, the need is dire: The US public broadly agrees that the country is currently suffering a mental health crisis, particularly among young people. Reports of loneliness and harmful thoughts among adolescents have risen substantially. The share of teenagers who said they have felt depressed nearly doubled from 2009 to 2019; 22 percent of US high school students said they had seriously considered suicide in 2021, up from 16 percent in 2011.

America’s young Black people are struggling more than most. From 2018 to 2021, suicide rates among Black youth grew at a faster rate than any other racial group, and Black high school students are now more likely than any others to attempt suicide. Black children ages 5 to 12 are twice as likely to die by suicide as their white counterparts. Many interventions for young people have failed to produce results, leaving experts in the field wondering where to go from here.

But for nearly three decades, Molock — an associate professor of clinical psychology at George Washington University and an ordained Christian minister — has struggled to get funding to even study Black suicides, let alone money to put her ideas for preventing them into practice.

The obstacles came early. In 1993, as an assistant professor of psychology at Howard University, she submitted an application to the National Institute of Mental Health for funding to study risk and protective factors for suicide among Black college students. The feedback from one of her application’s external reviewers previewed the climb she’d face for years to come.

The reviewer didn’t quibble with her research design or her hypotheses. They questioned the need for the project at all: If she was interested in suicide, the reviewer said, then she should focus on white men because Black people did not die by suicide.

Molock knew this wasn’t true. She had counseled children with suicidal ideas at her private practice. When she was training at the Howard University hospital, she saw Black patients who attempted suicide.

“My clinical experience said to me [Black] people did complete suicide. It didn’t go with my experience to say they didn’t do that,” Molock told me at her office on the George Washington University campus in Foggy Bottom. “So I can’t get this grant because you say it doesn’t exist? Let me show you.”

This is the story of Molock’s long march toward demonstrating the need for mental health programs targeted specifically to young Black Americans. It’s the story of decades spent building the empirical foundation for a program that would leverage the social connections of Black churches to stage suicide interventions. And it’s the story of one Black scholar’s trials in navigating a grant system that saw limited use for her work — and was skeptical of her methods.

But it’s a story with an encouraging middle, and reason to hope for a happy ending.

In 2020, Molock received funding from New York state for a project that combined her dual expertise: It would leverage the community connections of the Black church to build interventions aimed at bolstering the mental health of Black youth.

The program’s pilot phase was a success. Now Molock and her collaborators have received a much larger grant from a national nonprofit to expand it to a dozen more churches over the next year, while subjecting their model to a more rigorous evaluation.

Fifteen years ago, Molock observed that “there are no suicide prevention programs that are specifically directed at African American youth.” Today, there are still vanishingly few proven interventions to support young Black people who are struggling. If her project can demonstrate its impact, it would offer a light to a community that desperately needs it.

“I can’t stand that we stand by and do nothing for children,” she told me. “People talk about biblical abominations. That is the abomination for me: when we know kids are suffering and we’re not willing to do what it takes to change the world so they don’t have to.”

Back in 1993, Molock was eventually able to overcome reviewers’ skepticism about studying suicides among Black people. She did so by leaning into the institutional bias that was threatening to stop her work before she’d even begun.

When resubmitting the application, she pointed out to the reviewers that the US government had not historically broken out suicide data by specific race: It was white and “other.” There was a dearth of quality research on Black suicides.

“This is an empirical question,” she insisted. The institute decided to fund the study.

The seeds of that first project had been sown while Molock was working as a supervisor at an Auburn University student counseling center in the late 1980s.

The counselors, Molock noticed, would often hear about Black patients’ suicide attempts afterward, from somebody at the student health center or a residence hall, without the person having ever mentioned suicidal thoughts during their sessions at the center. Those young Black people didn’t know how to talk about their mental health struggles, she realized. Or they weren’t talking about those feelings in the same way as white students, whose behavior provided the basis for mental health screenings at that time.

“I became more curious. Well, if you’re not talking to your therapist, then who are you talking to? Are you talking to anybody?” Molock told me.

A few years later at Howard, Molock’s NIMH grant led to one of her first major breakthroughs. The research found young Black people did share some of the same risk factors for suicide as their white peers, but they also had unique ones. For example, the Black students who thought about suicide were less likely to say they felt hopeless when being screened for depression.

“They’re fatalistic about their futures. They feel that tomorrow is not really promised. Some of them don’t expect to see 30,” Molock told me. “So they’re not hopeless. They just feel like that’s the way life is.”

She would hold small groups with Black women and hear the same kind of fatalism: The participants may not describe themselves as traumatized or depressed. They had internalized that such experiences were inevitable.

Choir rehearsal at the Macedonia Baptist Church in Albany.

In 1997, Molock made another decision that shaped the course of her career; she decided to become ordained as a Christian minister. She had started having dreams about herself preaching. She resisted at first: “I experienced them as nightmares,” she told me. But after a year, Molock relented. She graduated from Howard University’s seminary in 2000. Her husband Guy followed in 2003, and the couple co-founded Beloved Community Church in 2008.

Molock’s next epiphany soon followed: “I was sitting in my office one day at home and I said, ‘You know what? I think I’m gonna do a prevention program for Black teens in churches.’”

But she needed more evidence. Molock’s scholarly work had thus far focused on college students. Now she wanted to interview middle and high schoolers to determine their risk and protective factors for suicide, with an eye particularly on whether they said the church was a positive influence in their life.

In 2000, Molock was looking for another round of funding. This time, she received an NIMH grant for career development — but only after once again facing skepticism about the need for her research. “There was this belief in the field that Black people didn’t do that,” said Jane Pearson, who led the grant program at NIMH and who advised Molock during the application process. “So she was working against that when she was coming in for a grant to look at Black adolescents.”

She published constantly over the next few years. Then, using what she had learned, Molock designed the first iteration of her church-based intervention program in 2007 — a plan she believed would help prevent suicides among Black youth.

But it would be more than 10 years before her idea would get the chance to prove itself.

Molock applied for grants from NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse to test her proposed intervention but was not accepted. Some of the feedback was positive, but she also remembers the objections, some of which were highly technical questions of methodology.

She acknowledges many of her peers weren’t accustomed to working in faith-based settings. They were struggling to apply academic rigor in a church. But the denials were “heartbreaking.” She began focusing on other issues in her academic work, such as HIV prevention.

Then in 2020 came the call that changed once more the course of her career.

Jay Carruthers, the director of suicide prevention in the New York State Office of Mental Health, had been scouting for interventions for Black youth that had some evidence for their effectiveness and he’d come up empty. He found and read Molock’s proposal for a church-based intervention. In August 2020, he called and asked Molock if she had data to demonstrate the model’s impact. She had to confess that, no, she did not. The project had never been funded.

“Well, would you like some seed money?” Carruthers asked her.

“I thought I had died and gone to heaven,” Molock said. The state authorized $75,000 for a small pilot project.

Molock also found the partners she needed.

Peter Wyman was co-director of the Center for Study and Prevention of Suicide at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, where he had pioneered a novel approach that sought to leverage people’s natural social connections to help them with depressive or suicidal thoughts. They combined their approaches, applying Wyman’s intervention model to the Black institutions Molock had identified as having high potential to reach struggling kids.

They were joined by Sidney Hankerson, then at Columbia University and now at Mount Sinai, who had grown up attending a Black church in Fredericksburg, Virginia, before studying psychiatry in college and joining the faculty at Columbia. Hankerson had already been working with churches in New York on mental health interventions, such as depression screenings.

The trio called their program HAVEN Connect.

Now came the moment of truth: How would they be received by the people they aspired to help?

Sanii, a high school sophomore whose family attends Albany’s Macedonia Baptist Church, was the kind of kid the program wanted to reach. Sanii said she was first bullied in middle school. Other students would insult her appearance. She had at times resorted to cutting herself to cope with those feelings.

Sanii’s family had been coming to Macedonia since she was 3. As a young single mother, Sanii’s grandmother Diane first gravitated to the church because of her kids; it gave her the extended family she didn’t have locally.

Her grandmother had seen Sanii struggling when the bullying began. She knew what that was like — Diane had been bullied as an adolescent too. But she admits she did not think to share her experiences with Sanii at the time. That wasn’t how she was brought up.

“You didn’t talk about mental health. You didn’t have the time,” Diane told me. “In my family, we were just trying to survive and provide. We were trained to handle it and be tough. There was no such thing as being depressed or ‘I got to talk to somebody about something.’”

It’s indicative of another major obstacle Molock has faced from the beginning. She has been forced to challenge misconceptions about Black people and suicide not only among other academics, but also within her own community, including the clergy in Black churches. They didn’t seem to recognize the mental health problems within their own congregation, and they weren’t comfortable talking about mental health or encouraging people to seek out clinical help.

She encountered those same attitudes in her own family. Molock remembers her dad would say when discussing her studies that his generation didn’t have to contend with mental illness. Those comments would puzzle Molock, because she knew members of her father’s family had been institutionalized. But he attributed those cases to a momentary breakdown. Such beliefs are deeply ingrained: Earlier this year, Molock’s aunt lamented to her that Black people had “gotten weaker.” Suicide didn’t used to be a problem for them, in her mind.

Molock has come to believe that her elders were reluctant to acknowledge any weakness, given the racism that they and those who had come before them faced. She points out a belief that Black people don’t die by suicide defies stories of enslaved people jumping out of ships on their way to the New World.

“Their perception is that white people always think poorly of them. This is another thing that white people or the majority culture can use to denigrate us,” she said of the older generations. “That means that people who are struggling with these issues can’t get help either. Because it’d be validating that there is something wrong with us. We’re already lazy. We’re already stupid. Now we’re crazy too?”

Many of the people I interviewed for this story described a reluctance in the Black community and even in Black churches to acknowledge mental health problems. Hankerson remembers a pastor from his youth saying, “Well, you don’t need to take Prozac if you pray.”

To succeed, HAVEN Connect would need church leaders who understood the need for mental health programs — and who would be willing to embrace them.

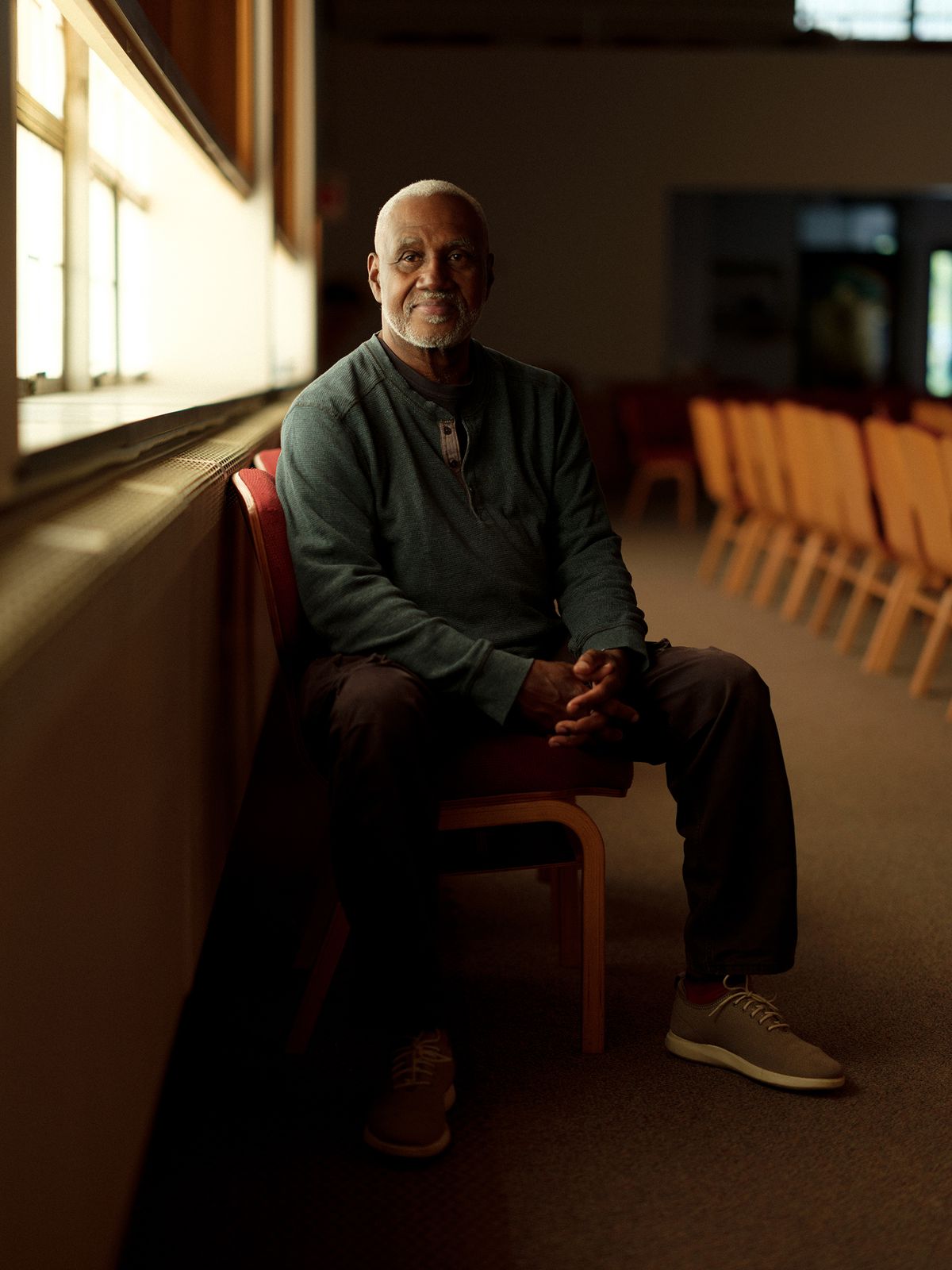

Hankerson had an in with Greg Owens, a deacon at Macedonia who had worked across New York state government in roles focused on children, when HAVEN Connect was getting underway. Hankerson asked Owens: Would Macedonia want to be a part of it? Owens was enthusiastic — and crucially, the church’s young new pastor, Rev. Michael-Aaron Poindexter, threw his support behind the project.

Then last year, over the course of six months, the researchers put their program into action at Macedonia, First Genesis Baptist Church in Rochester, and First Corinthian Baptist Church in Harlem.

HAVEN Connect looked different in each church, but the core themes were the same. In Albany, the research team held two-hour workshops over three days, both with young people and older people in the church, focusing on the principles that comprise the program’s curriculum: kinship, purpose, guidance, and balance.

Those concepts, based on Wyman’s work, are intended to strengthen connections within social groups as a way to improve vulnerable people’s mental health and their willingness to seek out help if they are struggling.

Macedonia’s HAVEN Connect workshops opened with an icebreaker, to loosen everyone up before the challenging material ahead. They alternated between large group discussions and smaller breakout sessions. Most of the participants came to the church’s spacious fellowship hall, but a few joined virtually.

HAVEN Connect also came to First Corinthian Baptist Church, located at the corner of 116th and 7th Ave. in Harlem. It’s an enormous church compared to Macedonia: 10,000 members on the roster and 1,500 people in its sanctuary, a converted movie theater, most Sundays. But much like Macedonia, it is a community hub, serving as a vaccine site during the pandemic, and a voting site every Election Day. It is home to a food pantry and a social services office.

When they hold youth events, many of the attendees are not members of the church, Lena Green, who leads a mental health program affiliated with First Corinthian known as the HOPE Center, told me. They had been trying to exploit that connection even before joining the HAVEN Connect project. First Corinthian started its own 12-week “youth resilience” program called Thrive. It is composed of two-hour sessions, which start with a meal and then activities and discussions that focus on themes like violence and social media.

When the HAVEN Connect team contacted them, “it was a perfect match and an answered prayer,” Green said. First Corinthian held its own series of workshops based on the program’s concepts and has sought to integrate them into the ongoing Thrive sessions as well.

“I’ve had aunts come to me and say, ‘I can see my niece’s posture has changed,’” Green told me. “‘The way she talks to adults, the way she expresses herself.’”

For Sanii in Albany, the project was crucial to setting up a support system in her struggle with mental health. HAVEN Connect inspired her to lean on kinship, on her relationships with other people, to navigate difficult moments. She has set up a small informal support system, a few kids from her math class (her favorite subject) in whom she can confide when she needs to.

Even so, she must contend with the same stigma that has clouded Molock’s work for decades. I asked Sanii how people in her class deal with mental health problems.

“I feel like they’re scared to say it, because I feel like they feel like people are going to judge them or make fun of them for feeling that way,” Sanii said. “And they think they can’t go to their parents because their parents were just going to brush it off and say that, ‘Oh, they’re too young to feel this way.’ Or, ‘They’re too young to be going through something like that.’ So that’s why they just hide their emotions and just pretend like everything’s okay.”

Diane has also tried to put the kinship principle into practice. The day after attending the HAVEN Connect workshop, she started a group chat with family who live in the South. It’s still going: They have Throwback Thursdays, when they post clips from sitcoms they used to watch, and Dance Battle Fridays, when they share clips of one another and vote on whose moves are most impressive.

“That’s kinship,” Diane told me. “Keeping that connection strong. Keeping a connection with everybody.”

The HAVEN Connect workshops were a year in the past when I visited Macedonia Baptist Church in late October. As I sat with Owens, the deacon, in the pews of the sanctuary, he described his challenge now: to make the program’s principles part of the everyday life of the church.

“You don’t have to make a big deal out of it. But you begin to ask questions that can result in people saying, ‘You know, I don’t feel good about myself,’” Owens told me. “This is the stuff that we should be talking about. You and I should be talking about balance in life, right? Because we can all get unbalanced.”

They are reaching out into the community as well. The week after I was there, Macedonia hosted a “glow night” for Halloween, inviting neighborhood families to come in costume for candy and activities. The church holds an annual block party and organizes field trips to amusement parks, free of charge to local children.

“I don’t care if you’re a member or not,” Poindexter said. “My goal is to impact you and show you we care.”

That will be the next objective for HAVEN Connect: evaluating its impact. Last year’s pilot programs were largely assessed on one-time experiential survey data, which looked promising. Participants almost universally said they felt more prepared to handle life’s challenges and to identify people who could support them. The people working in these churches are convinced of the project’s success.

But soon Molock will have more robust empirical data on the project that is the pinnacle of her life’s work.

Molock, Hankerson, and Wyman have received a $1.5 million grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to expand the HAVEN Connect program to 12 more churches and more rigorously study its impact. They are comparing the experiences of children who participate in HAVEN Connect with those who don’t, following up one month after the program and then again six months later.

They are expecting the kids who take part will report decreased depression symptoms and a lower suicide risk. The researchers will also assess whether participants say they have stronger bonds with their peers and can better regulate their emotions, and whether they take advantage of clinical services more as time passes.

If Molock’s long-held hypotheses hold up, the data will demonstrate how a cultural change at a church can help its vulnerable young people feel more supported. I asked her to describe that change in her own words.

“People would talk about mental health in the pulpit all the time. We would normalize this conversation,” she replied. “It would not be embarrassing to talk about being depressed. We could say someone died by suicide at their funeral and not have people feel embarrassed or ashamed. But we hopefully would prevent those things from even happening.”

She faces new headwinds. Surveys reveal that Gen Z is less likely to attend religious services than their elders. Poindexter said Macedonia continues to add members, including young families, but acknowledges that society is drifting away from faith. Still, he asserted, churches continue to play a prominent role in Black communities.

Part of the idea behind the program’s principles is supposed to be their adaptability. Wyman first used them in the military and in high schools. HAVEN Connect took them to Black churches. Hankerson recently received a new grant to work with youth basketball leagues.

When I met her on campus in September, Molock still radiated the tenacity that had been necessary to get through those decades of tribulation. She notes, with a laugh, that her husband will warn people that they should never tell her no. (He confirms: “I saw her struggle. I saw the frustrations. However, she was steadfast. It never stopped her or deterred her from going forward.”)

That faith got her here. HAVEN Connect is a reality, and it’s expanding.

“This is what I live and breathe. This is my raison d’etre. This is why I’m here,” she told me. “Until I can’t breathe anymore, I’ll always do it.”