The day after President Joe Biden said he would not seek reelection, his White House announced more than $4.3 billion in grants from the Environmental Protection Agency to communities to curb climate change, cut pollution, and seek environmental justice.

It’s a big announcement, but easily lost amid the thunderous presidential campaign news.

The grants will fund projects across the country that include decarbonizing freight, installing geothermal systems, and capturing fugitive methane emissions. According to the EPA, these grantees will cut US greenhouse gas emissions up to 971 million metric tons by 2050. That’s equal to the emissions of five million average homes over 25 years.

Amid all the political pandemonium, it’s remarkable that the administration is continuing to pump out new environmental initiatives. Climate has consistently been a high priority for the Biden administration, and this announcement proves a genuine commitment. Biden has the distinction of introducing the earliest bill in the Senate to address climate change, the 1986 Global Climate Protection Act. Humanity, though, has more than doubled its greenhouse gas pollution since then. As president, Biden has made dealing with global warming an even higher priority than it was during his last turn in the White House as vice president.

The United States is the world’s largest historical emitter of greenhouse gasses and is currently second in annual output, behind China and ahead of India. So on the world stage, the US has a significant role, and activists say a responsibility, to nudge the global warming trajectory downward.

When he leaves office in January 2025, Biden will be able to credibly claim that he has done more on climate change than any other president and has been one of the most consequential decision-makers in the world for the future of the planet.

But while he’s done the most, it’s still not enough to get the US in line with Biden’s own climate change goals. Many of Biden’s environmental initiatives are still struggling to get rolling, and some activist groups are not satisfied with what he’s done.

And if Donald Trump wins in November, that progress will stall.

What Joe Biden has done for the climate

When Biden was one of nearly two dozen Democrats running for the top job in 2019, he proposed an extensive climate plan released in two installments that emphasized cutting greenhouse gas emissions by building up a robust US clean energy sector with $2 trillion in investment. He also laid out a legislative strategy and a list of executive actions he would take on his own, such as imposing tough methane leak restrictions on new oil and gas facilities, requiring federal government operations to procure clean energy, and imposing new efficiency regulations on appliances. At the same time, Biden’s plan was seen as less ambitious than those of his competitors — Bernie Sanders called for $16.3 trillion in total — and he was criticized for declining to support a ban on fracking and for attending a fundraiser hosted by a natural gas company founder.

But since taking office in January 2021, Biden has demonstrated that at least part of his plan was realistic: He managed to tick many of the items on his to-do list that are directly under the president’s purview or from cabinet agencies.

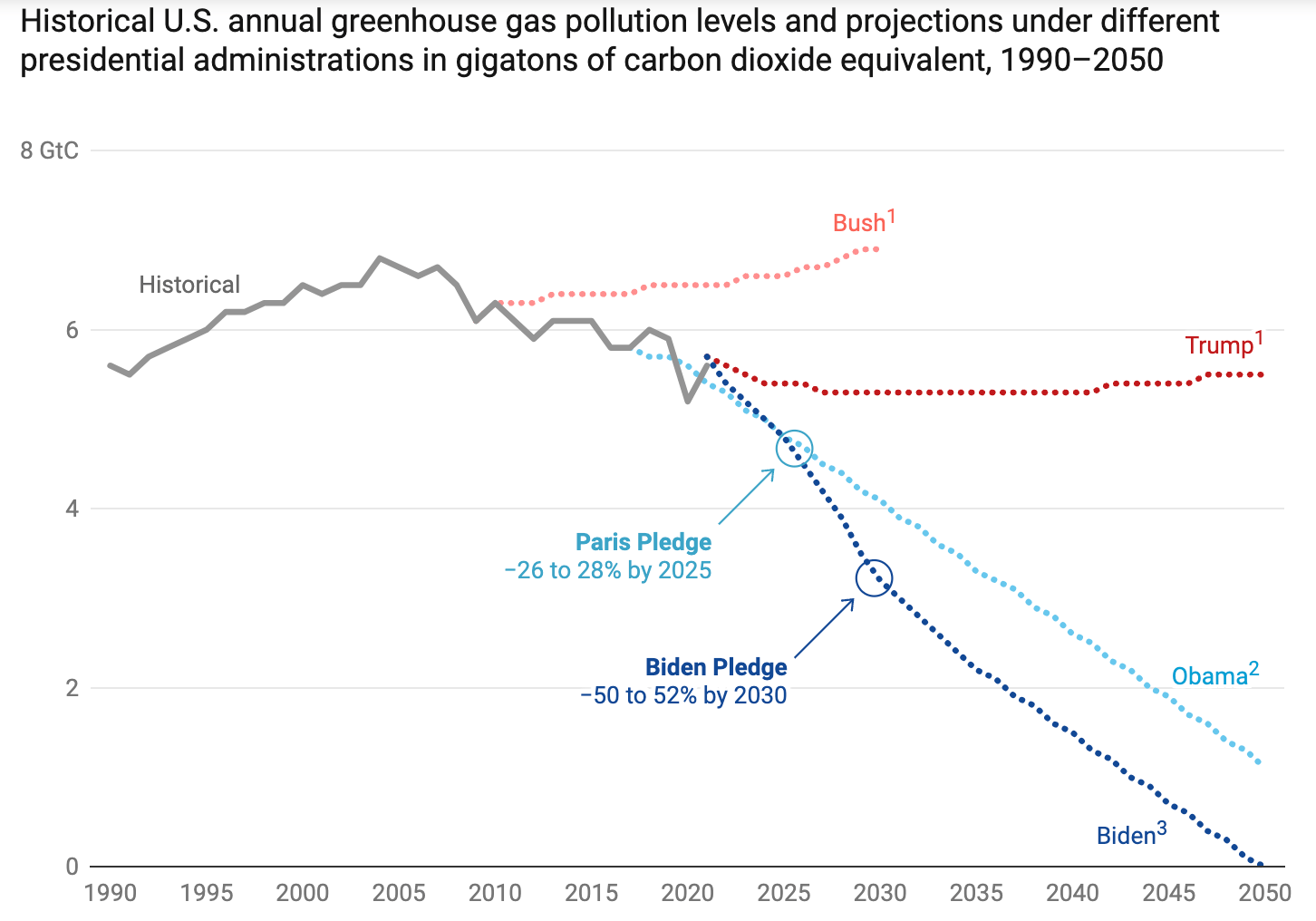

He brought the US back into the 2015 Paris climate agreement, personally attended international climate talks, and committed the country to a more ambitious goal of cutting carbon dioxide emissions in half from 2005 levels by 2030 while achieving net-zero emissions across the economy by 2050. His administration enacted new fuel economy regulations for cars and trucks to encourage electrification. It set stringent caps on air pollution and carbon dioxide from fossil fuel power plants. It raised efficiency standards for stoves, refrigerators, and shower heads. It set zero-emissions targets for federal buildings, energy suppliers, and vehicle fleets, including placing orders for at least 45,000 electric mail trucks. It vastly expanded federal protections for public lands and established a Civilian Climate Corps to train workers to maintain them.

Perhaps Biden’s single most impactful climate action was signing the Kigali Amendment, an international treaty to phase out some of the most powerful greenhouse gasses. On its own, the Kigali Amendment would avert almost 1 degree Fahrenheit of warming by the end of the century. On September 21, 2022, it cleared the Senate with bipartisan support, including 21 Republicans.

With Congress, Biden signed the trio of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act. While climate change isn’t in their names, these laws mobilized billions of dollars in investments in clean energy, infrastructure, battery manufacturing, and building up supply chains. Together, they’re some of the largest investments in climate change mitigation in the world. Additionally, they’re structured as incentives, with no explicit penalties for carbon dioxide emissions.

Getting these laws passed was a bruising fight. Biden’s signature Inflation Reduction Act in its final form — with $370 billion for clean energy deployment — was a fraction of the size of the $1.75 trillion version that passed the House in 2021. The Democrats’ narrow majority in the Senate gave holdouts like West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin leverage to chip away at its scope while securing more pot sweeteners for his own state. That in turn drew the ire of environmental activists who were anticipating a much more robust law.

Much of the IRA’s costs come in the form of tax breaks rather than new spending. “The IRA’s projected costs to the U.S. federal budget are mostly reductions in taxes owed by U.S. taxpayers or increases in federal payments to those taxpayers,” according to a Treasury Department analysis.

Still, the IRA remains the largest investment to deal with climate change in US history.

Politics and Biden’s own policies undermined his climate ambitions

Biden has also had to navigate political rapids over the past four years and has ended up getting turned around on occasion.

For instance, Biden campaigned on banning new oil and gas development on public lands (on a page since deleted from his website), but in 2022, the Interior Department opened the door to new drilling lease sales. One example is the Willow project in northern Alaska, which the Biden administration greenlit last year, that could extract more than 600 million barrels of oil over 30 years.

Fossil fuel projects like this have led to some of Biden’s biggest climate contradictions.

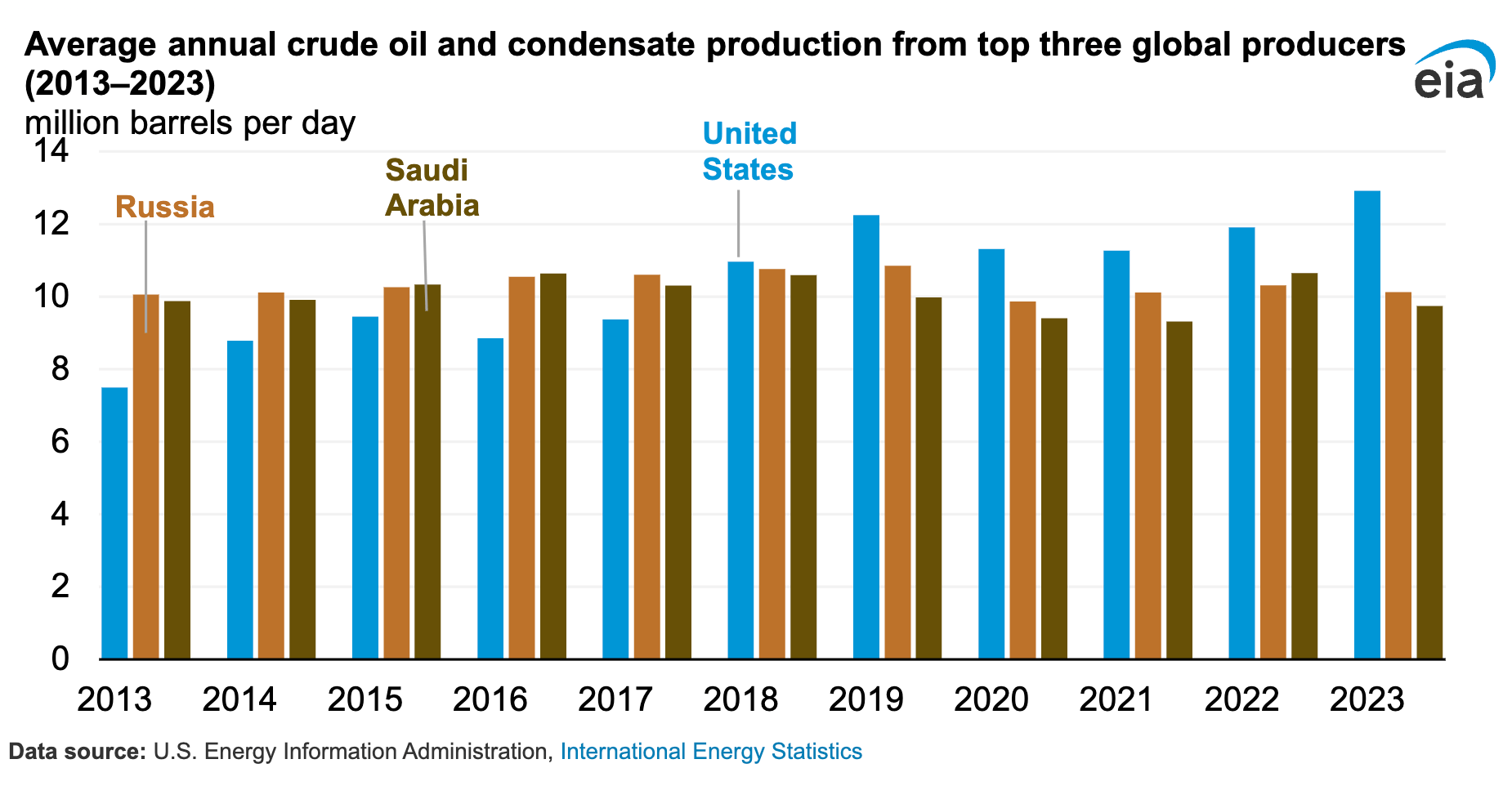

On Biden’s watch, the US has become the largest oil and gas producer in history. US exports of natural gas hit a record high, especially after the administration stepped up deliveries to allies after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Even though the US is aiming to slash its domestic emissions, the country is on track to double liquid natural gas (LNG) exports by 2030. But Biden also imposed a pause on new liquefied natural gas export terminals pending a review of their environmental and national security bona fides.

When desperate to tamp down inflation and smooth over supply chain disruptions stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic, the White House tapped the strategic petroleum reserve to help bring gasoline prices down. Biden has bragged about lowering gasoline prices. These lower prices tend to spur more driving, which in turn increases greenhouse gas emissions.

America’s fossil fuel bounties have put the Biden White House in the awkward position of taking credit for facilitating their production while simultaneously trying to curb their use.

Biden’s policies have also created friction within his climate goals.

His signature legislation, the IRA, has provisions mandating that cleantech companies build their products and supply chains in the US if they want to tap the money in the law. The provision has angered allies in places like Europe that want to sell products like solar panels and efficient appliances to US customers. Biden has also retained many of former President Donald Trump’s tariffs on foreign goods and is imposing new ones on cheap electric vehicles made in China by companies like BYD, currently vying with Tesla to be the largest pure EV maker in the world.

This protectionism for US companies raises prices for American buyers and means that the shift to clean energy is more expensive and slower than it needs to be. On the other hand, if cheaper cars and solar panels did enter the US market, they could get more Americans off of coal, oil, and natural gas at a faster pace.

America’s progress on climate change is fragile

The question now is whether US climate policies will continue to gain momentum, stall, or reverse. The main hinge point is who wins the next election.

Vice President Kamala Harris, the likely Democratic presidential nominee, has her own history with tackling climate change as California’s attorney general. And with Biden’s endorsement, the Venn diagram of their climate policies will have a lot of overlap.

However, there are some big obstacles. Few Americans grasp how they can benefit from the programs in the IRA, and the money in the law has been slow to trickle out to build things like EV charging stations. Shortages of specialized labor and permitting issues have delayed big clean energy manufacturing projects. Energy demand is poised to grow as well, driven by population growth and technologies like artificial intelligence, and already fossil fuels are feeding some of that new appetite.

Biden’s policies are facing legal setbacks too. Republican state attorneys general are suing the White House to block new fuel efficiency regulations for cars and trucks. The Republican-led Supreme Court has also eroded the federal government’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, and with the recent reversal of the Chevron doctrine, agencies like the EPA will have much less leeway to craft environmental rules.

It’s also not clear voters will reward the effort. A majority of Americans support addressing climate change and deploying more clean energy, but it ranks as a much lower priority behind issues like crime and inflation. According to the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication in a survey conducted in April 2024, 37 percent of US voters consider climate change to be “very important.”

Vice President Kamala Harris speaks at the COP28 climate change summit in the United Arab Emirates in 2023.Hollie Adams/Bloomberg via Getty Images

On the other hand, Trump, the Republican nominee, is openly disdainful of action on climate change. A key focus of his first turn in office was systematically undoing or blocking environmental regulations and promoting fossil fuels, going as far as removing the words “climate change” from government websites. Many of these rollbacks were stalled because they were poorly structured, blocked by courts, or undermined by bad staffing choices.

Conservative activists are working to ensure they don’t squander another opportunity in the White House to achieve their goals. The Heritage Foundation laid out a strategy for this in Project 2025, which aims to staff federal agencies with people who will reduce regulations and increase fossil fuel development. Though Trump has sought to distance himself from the plan, many alumni from his administration and campaign personnel were among the authors.

And there’s always the chance of another shock — a war, a pandemic, a depression — that could take the wind out of the sails of curbing climate change.

Despite this uncertainty, it’s increasingly clear that the turn toward cleaner energy is likely to endure. Worldwide, wind and solar are the cheapest sources of new electricity, and in some cases more cost-effective than existing fossil fuel sources. Market forces and climate policies are starting to have an effect, and according to some estimates, the world may be close to reaching peak greenhouse gas emissions, if it hasn’t already crossed this line.

Even with so many potential setbacks, some of the big changes Biden set in motion are likely to stick, as the cleaner, more efficient technologies become cheaper and more polluting sources of energy enter their final days. Even if Trump were to retake the White House, it’s likely that US emissions will continue to decline, albeit not as quickly as they would under a Democrat.

Changing this course took decades of persistent effort from scientists, engineers, leaders, and activists. Joe Biden deserves some credit for helping turn the rudder.