February 3, 2022:

There are 15 sports and 109 events at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, but the crown jewel of these games is the beautiful, rigid, surprisingly complicated bloodsport known as figure skating.

It all seems simple enough. The parameters of the sport are finite: Skaters are limited to about seven combined minutes of skating between the short and long programs and only six allowed jumps. They’re bound by the laws of gravity. The cardinal rules remain “more rotations are better than fewer rotations” and “don’t fall.” Still, the way skating is scored can be hard to decipher.

Figure skating is all about the minute details. It’s a competition that comes down to microseconds, a half-degree of an angle, and decimal points. Every four years, skaters pour in a lifetime of effort — thousands of jumps and spins and falls; hours and hours of flexibility exercises; nagging injuries; an inordinate amount of time spent in the cold — into less than 10 minutes of skating.

And while it requires superhuman strength and balance, the sport has traditionally had an artistic side, too. The way a skater moves through the ice and the shapes they create are supposed to be beautiful. There is an unquantifiable aspect that some skaters have that makes you never want to stop watching.

The scoring system — which favors athleticism, especially jumps — is controversial, and it speaks to a debate about what figure skating is supposed to be. I spoke with former skaters, experts, and even physicists to explain how scoring and jumping works in figure skating, in the plainest English possible.

Over the past three Winter Olympics, experts, skaters, and fans have debated whether the figure skating event has become more about sheer athleticism and much less about artistry and presentation. Is figure skating a jumping contest, or is it a performing art? Can you have both athleticism and artistry? And what happens when the sport starts favoring one aspect over the other?

The controversy all stems from the current scoring system.

Two decades ago, figure skating was rocked by the competition-fixing scandal that affected the Olympic pairs and ice-dancing event. Investigations found that there was vote swapping with judges abusing the subjective scoring method (the old system was based on two ranges of scores — artistic and technical merit — that top out at 6.0). In an effort to make a system that was less prone to abuse, a new method that focused on quantifiable numbers took shape.

Fully implemented in 2006, the current system assigns numeric point values to jumps, spins, and other technical elements in a skater’s program, in an attempt to standardize the potential scores for those elements. The idea is that if you break down an entire routine’s features and elements to numbers, there’s less room for subjectivity. Each of those elements has a base value, and judges score how well a skater performed the trick on a -5 to +5 scale which is called the Grade of Execution (GOE). An element hit perfectly would nab an athlete that element’s base value and a +5 GOE, increasing their total. An element not quite done correctly would nab a lower GOE and deduct their base value.

For skaters, the new scoring system makes it easier to show improvement or regression from competition to competition (i.e., the same program is going to score better the better you are at skating it). It also puts the entire field into perspective. Everyone knows what scores they have to beat to get on the podium.

To achieve the best possible scores, skaters have to hit their jumps.

Of all the tricks in a routine, the six recognized jumps — the toe loop, the loop, the salchow, the flip, the lutz, and the axel — are elements worth the most points. At this point, quads, which are versions of these jumps in which the athlete performs 4 to 4.5 revolutions, are the human limit. Skaters are allowed three jumping attempts (or passes) in their short program, which encourages skaters to maximize the difficulty of jumps.

In their free skates or long programs, skaters get seven passes and they aren’t allowed to repeat a jump unless it’s in combination (i.e., skaters can’t cram a program with one or two jumps that they’re really good at). In free skates, skaters are also allowed three combination passes — jumps done one after the other — which yield the most points. And finally, skaters are allowed three jumping passes in the second half of their routine, which yield a 10 percent bonus, ostensibly a reward for being able to land difficult jumps when fatigue kicks in.

Because of the way quads and quad combos are scored, it can lead to a slightly confusing situation. Theoretically, and it’s happened in the past, a skater with a sloppier, high-risk routine can score higher than a skater with a clean routine with less difficulty. The current system rewards risk.

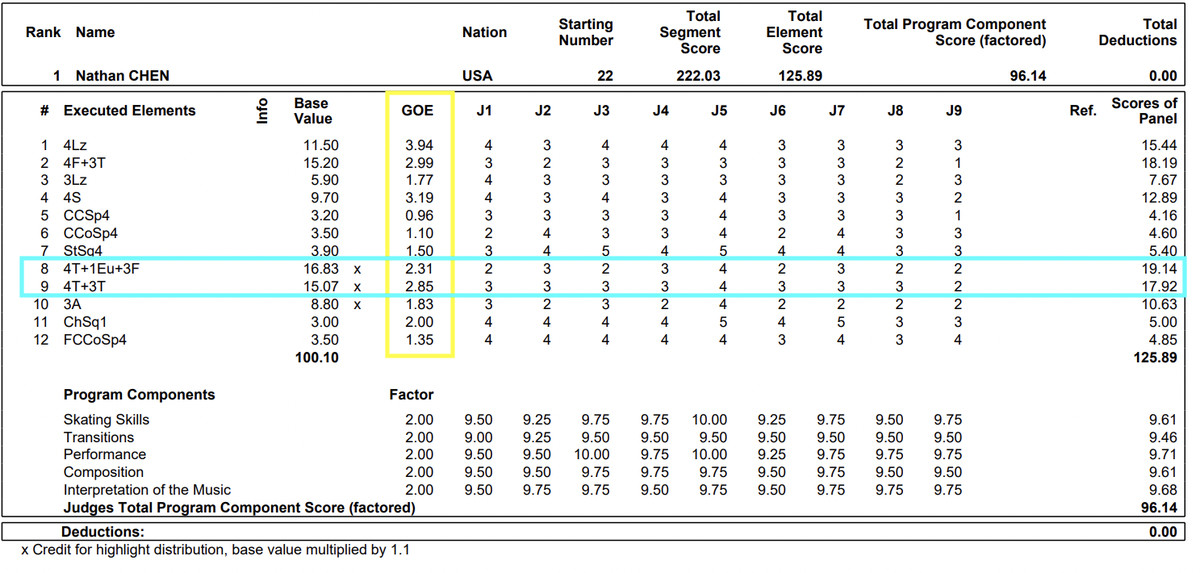

To see these points in action, here’s Nathan Chen’s free skate scoresheet from the 2021 World Championships. You’ll notice that he scored roughly 125 points from his “executed” elements — a large number of those coming from his combination passes, quadruple jumps performed with positive GOEs:

At the bottom half of this scoresheet is the Program Components score, or what’s considered the artistic aspect of the routine. The categories are skating skills, transitions, performance, composition, and interpretation of the music. Each category is judged on a scale of 1 to 10. Those are then averaged out, and the total is multiplied by two in the free skate. The PC’s max out at 100 points in the free skate and 50 in the short program. As you can see from Chen’s score, the elements outweigh his very high artistic marks.

Under this scoring rubric, if the skater had to choose what to focus on, jumps and spins would be the no-brainer pick. They’re worth more. But as skaters trend toward jumps, some may neglect the artistic side to their skating.

“In terms of artistic growth, some of the programs that we’re seeing now are just stroking patterns into jumps, and there’s really no performance aspect anymore in that,” Polina Edmunds, a former Olympian and US National silver medalist, told me. Edmunds retired from skating in 2020 and hosts a skating analysis podcast.

“That’s not true for all skaters. There’s some that are doing a good job of combining both artistry and jumps. But in general, I would definitely say, the artistic side of women’s skating has decreased a lot because of the numbers game that we’re trying to play,” she said, explaining that while scoring has pushed the athletic prowess of the sport to new heights, it has also deemphasized some of its artistic beauty.

When she sprang into national prominence at 15 in the Sochi Olympics, Edmunds was primarily known for her jumping ability. She said that judges and coaches told her that artistry would come as she got older and “grew” into her skating, and the scores would reflect that. But Edmunds said because of a combination of high turnover in skating, especially women’s, and judging becoming more lax when it comes to artistic merit, that mentality has ceased. There’s also some overlap between the artistic score and the jumping score.

Skaters are being awarded artistic points for their jumping abilities, she explains, which means that performing quads automatically puts a skater’s program components score at a higher number.

“In my opinion, just because you can do jumps doesn’t mean you can do really intricate footwork in your program,” Edmunds said. “And so I think that’s kind of the flaw in the judging system right now that needs to be corrected, where in order to balance it out, they need to be judged appropriately for their actual artistic ability.”

There’s a lot going into those jumps, from a physics perspective. Michalis Bachtis, a physics professor at UCLA, explained what factors into a figure skater’s jump, saying to think of the jump itself as the way mass is spread multiplied by how fast someone is revolving. Skaters want to eliminate the spread of that mass and get as tight and narrow as possible — think of how fast a pencil spins when you rub it in between your palms. That’s why they pull their arms tight in the air, and open their arms as they prepare to land, to reduce the stress on their feet and ankles. All of this happens in a split second.

What amazes Bachtis is that skaters actually land these jumps — that they manage to fight torque, the spinning, twisting force that occurs when their blade hits the ice again.

Brad Orr, a professor of physics and the associate vice president for research, science, and engineering at the University of Michigan, explained that it is a quirk of skaters’ physiques that they’re able to land. “I mean, I think all these people are genetic freaks,” he said, clarifying that he means that as a compliment. He speculates that core and leg strength — as well as bearing a little shorter than the average Olympian — is a large part of this seemingly superhuman ability.

The athletic push over the past eight years has made it so that in order to medal on the men’s side, you need to be able to hit quad jumps since so many of the best men’s skaters — Nathan Chen, Yuzuru Hanyu, Yuma Kagiyama — in the world have them. The women’s side this year is dominated by quad-landing Russians.

“I would say Chen probably will go for five quads at the Olympics, most likely,” said Dave Lease, who runs The Skating Lesson, a YouTube channel devoted to everything skating.

“For the women, you may need a quad [in the free skate] to win gold. … But women aren’t allowed to do quads in the short program — it’s an old rule and a constant source of debate. Where the women can get ahead is if they can do a triple axel in the short program,” he said, naming the jump worth the most points. He highlighted Russians Kamila Valieva, Alexandra Trusova, and Anna Shcherbakova as this year’s frontrunners.

To put that in perspective, four years ago at the 2018 Winter Olympics, no women landed a triple axel in the short program.

The better the skaters are at landing quads, the higher the value, the higher the GOE, and the more points you can get from a skill. And there’s a clear gap between skaters who have quads in their arsenal and skaters who don’t.

Jumps are truly the name of the game. If there’s one thing we can count on this Olympics, it’s seeing tiny humans spin through the air, trying to rack up big scores.