May 3, 2024:

Young John Roberts was a funny guy.

“The generally accepted notion that the court can only hear roughly 150 cases each term,” the future chief justice wrote while he was an early-career lawyer working in the Reagan White House, “gives the same sense of reassurance as the adjournment of the court in July, when we know that the Constitution is safe for the summer.”

Roberts, of course, wrote this at a time when Republicans could not rely on the federal judiciary to advance its policy goals — something that Roberts has done much to change in his current job. The justices are in the middle of an unusually political term, fraught with cases that tweak many of America’s most bitter divides on issues like guns or abortion, and that seek to fundamentally restructure who wields power in the United States.

That includes two cases — one already decided, the other still pending — which seem engineered to shield Donald Trump from any meaningful consequences from his attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election. The coming weeks will see decisions in two cases that are likely to shift an extraordinary amount of policymaking authority away from an elected president and toward an unelected judiciary.

Yet, while the justices seem eager to be the final word on America’s most intractable political divides, they’ve increasingly stopped doing the traditional work of judges — resolving often technical, boring legal disputes that arise between litigants whose names will never be mentioned on cable news.

The Supreme Court used to do this work. But it avoids it more and more now. Indeed, one striking thing about Roberts’s Reagan-era quip about the Court’s docket is that he describes a Court that “can only hear roughly 150 cases each term.” Now, the Court is hearing barely more than 60.

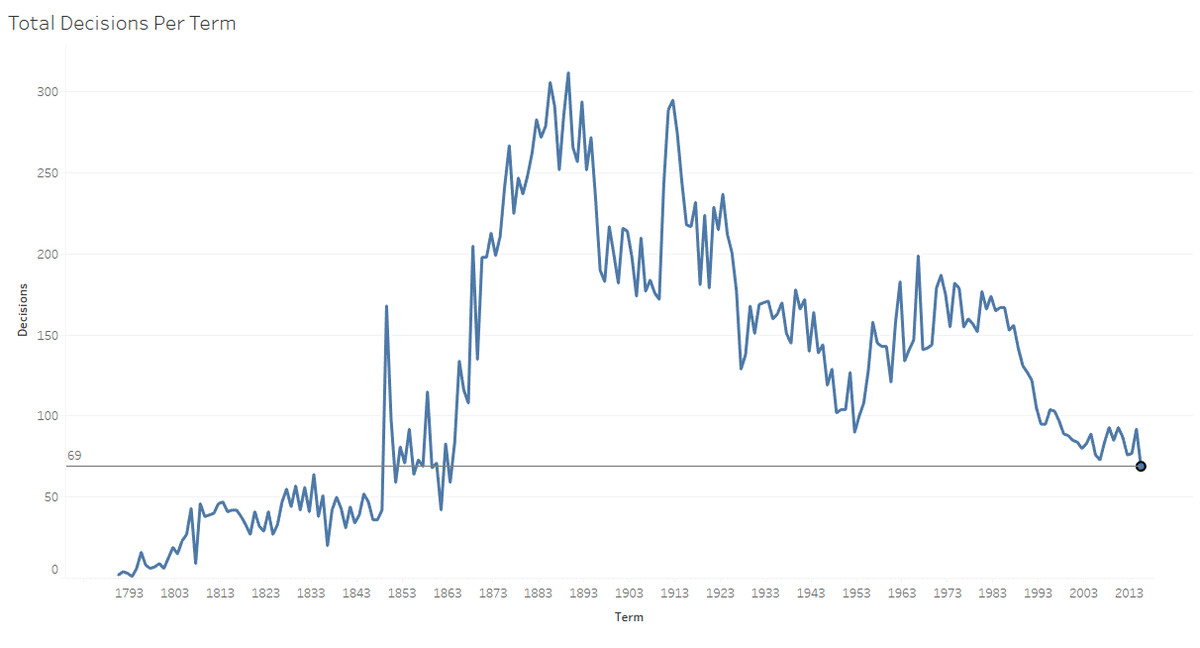

Consider this chart, which was produced by Adam Feldman, a lawyer and political scientist who publishes empirical work on the Supreme Court. Although slightly dated (it ends with the Court’s 2016–17 term), the chart shows the total number of cases that the Court handed down in each of its annual terms on its merits docket — the cases that typically receive full briefing and oral argument before the justices:

Adam Feldman/Empirical SCOTUS

Feldman’s data shows a steady decline in the Supreme Court’s workload since the 1960s. By the mid-2010s, the Court was deciding fewer cases than it had since the Civil War and Reconstruction.

And this trend is continuing. In the Court’s 2013 term, it decided 79 cases on its merits docket. This term, assuming that none of the Court’s pending cases are dismissed, it will only hand down 61 decisions.

Because the size of the Court’s docket has been in steady decline for many decades, there’s been a great deal of scholarship examining why this decline is happening. The striking thing, however, is that the size of the Court’s docket continues to shrink, even after many of the most likely explanations fade into the past.

Many scholars, for example, point to the Supreme Court Case Selections Act of 1988, a federal law that gave the justices more ability to turn away cases they don’t want to hear, as a significant driver of the Court’s reduced caseload. Yet, while a 1988 law can certainly explain why the Court is hearing fewer cases today than it did in the early 1980s, it does little to explain why the Court heard about 23 percent fewer cases in its 2023 term than it did in its 2013 term.

It is unlikely that there’s a single explanation for the Court’s shrinking docket. Scholars and other legal experts have all proposed numerous overlapping explanations for the reduced caseload.

One thing is clear, however. The overall decline in the Court’s docket does not appear to be matched by a decline in the number of political cases heard by the justices. That is, while the justices are hearing fewer total cases than they used to, they are avoiding the kind of technical legal disputes that rarely garner headlines — all while vacuuming up more power to decide the kind of political disputes that divide Democrats from Republicans.

Until the late 19th century, the justices had very little control over their docket. Litigants who lost in a lower court typically could bring their case to the Supreme Court whether the justices wanted to hear that case or not. This changed in 1891, when Congress enacted legislation creating mid-level courts that would hear most federal appeals and gave the Court discretion to turn away at least some cases.

Two subsequent laws, enacted in 1925 and 1988, further reduced the Court’s mandatory jurisdiction. The justices now have the freedom to turn away nearly all of the cases that are brought to their attention. Today, in the overwhelming majority of cases, four justices must agree to hear the case or the lower court’s decision stands.

Beyond this 1988 law, an internal change in the Court’s process for deciding which cases to hear may contribute to its reduced caseload.

In a typical year, the Court receives thousands of petitions — known as petitions for a “writ of certiorari” — asking it to hear a particular case. Prior to the 1970s, at least one law clerk in each of the nine justices’ chambers would typically review each of these petitions and advise their justice on whether the petition should be granted. After Justice Lewis Powell joined the Court in 1972, he decided that this process was needlessly inefficient, and urged his colleagues to pool their chambers’ resources.

The result was the “cert pool.” Under this process, petitions asking the Court to hear a case would be randomly assigned to just one clerk among all the justices who participate in the pool. These justices would all rely on a memo drafted by that one law clerk to advise them on whether to hear the case. Initially, five justices joined the pool, though that number has fluctuated, and it now includes every member of the Court except for Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch.

Several court-watchers have blamed this process for the Court’s reduced docket. As Ken Starr, the former federal judge and US solicitor general best known for investigating President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, wrote in a 2006 essay, “this efficiency-driven device has been inadequately studied, but what is commonly understood is that the prevailing culture within the pool is to ‘just say no.’”

That is, law clerks are reluctant to recommend that the Court hear a case because they don’t want to be embarrassed if the case turns out to be a dud. And with so many justices participating in the pool, many justices’ decisions will be influenced by a single timid clerk.

Yet, while policy changes like the 1988 law and the implementation of the cert pool might explain why the Court hears fewer cases now than it did in the 1970s, they cannot explain why the size of the Court’s merits docket continues to decline to this day. These are, by now, well-entrenched, decades-old reforms. Whatever impact they might have had in the past is now baked into the Court’s year-to-year work.

Other scholars point to changes in the Court’s personnel to explain the shrinking docket. In a 2010 essay, David Stras, a former law professor who Trump later put on the federal bench, argued that, in the early 1990s, three justices who voted to hear a relatively large volume of cases were replaced by justices who wanted the Court to hear fewer cases.

The most dramatic shift was the replacement of Justice Byron White, who believed that the Supreme Court had an obligation to resolve disagreements among lower courts very quickly, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. According to Stras, White voted to hear a case an average of 215.6 times per Term between 1986 and 1992. When Ginsburg joined the Court, by contrast, she voted to hear only 63 cases during the 1993–94 term, “or 29.2% as often as her predecessor.”

Yet, again, while these personnel changes might explain why the Court’s docket shrunk in the mid-to-late 1990s, they do not explain why the trend continues nearly four years after Ginsburg’s death.

In a 2012 essay, scholars Ryan Owens and David Simon offer another explanation for the diminished docket. For much of the post-1960s period when the Court’s docket steadily declined, the justices were ideologically divided. As a result, any individual justice would “be less sure of outcomes and will anticipate more dissents and internal strife” if they agree to hear many cases. Owens and Simon argued that “such a Court will decide fewer cases” because justices will be reluctant to hear a particular dispute if they cannot predict how their colleagues will view the case.

This thesis made a lot of sense in 2012, when the Court was divided 5-4 between conservatives and liberals, and when the balance of power had long been held by “swing” justices like Powell or Justices Sandra Day O’Connor or Anthony Kennedy, who were relatively moderate conservatives who frequently made common cause with the Court’s more liberal bloc.

But the Court in 2024 is vastly different from the one that existed a dozen years ago. Now, Republicans enjoy a 6-3 supermajority on the Court, and moderate Republicans like O’Connor and Kennedy are an increasingly distant memory. The Court is far more ideologically cohesive than it was in 2012, and yet its docket continues to shrink.

When I asked Owens and Simon if their views have evolved since they published their 2012 paper, Owens pointed to the Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), an LGBTQ rights victory authored by the Trump-appointed Gorsuch, as evidence that there are still “sufficient differences among the conservatives that nothing is guaranteed.”

But even though real divides do exist among the Court’s Republican appointees, the Court certainly has not become less ideologically coherent than it was a dozen years ago. And yet the size of the merits docket continues to shrink.

So a complete explanation for why Court’s caseload has almost relentlessly declined over the course of the last six decades remains elusive — although, as Owens said to me over email, there is probably a good explanation for why the Court is unlikely to reverse course. “A small docket has become the new norm.” he told me. “It’s been so small for so many years now that going back to > 100 would be really odd.”

Inertia is a powerful force, and increasing the size of the docket today would require a critical mass of new justices to break with a well-established status quo.

One area where Owens and I seem to agree is that, while the overall size of the Court’s docket is in decline, the Court continues to hear at least as many politically contentious cases as it did in previous decades. As Owens put it in his email to me, “the Court has decided to hear fewer cases—but a greater percent of cases with national importance.”

Even if the current term, which has been mired in the giant sucking vortex that is Donald Trump, is an outlier, the last several terms have featured an array of highly partisan cases that have fundamentally reworked some of the most contentious areas of US law. Roe v. Wade is gone. So is affirmative action at nearly all universities. Thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022), gun regulations of all kinds are now in jeopardy. The Court keeps inching us closer to a world where religious conservatives can simply ignore anti-discrimination laws.

The Court’s current majority has flooded the zone with decisions remaking the law in areas that the Republican Party cares deeply about. Just one month after Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation gave Republican appointees a supermajority on the Court, for example, the Court handed down one of its most significant religion cases in three decades — giving religious conservatives a broad new right to ignore state laws they object to on religious grounds.

And this decision was only the first in a wave of cases revolutionizing the Court’s approach to religion. As I wrote in a 2022 article, the Supreme Court heard only seven religious liberty cases during the Obama presidency. By contrast, it decided just as many religious liberty cases before Barrett celebrated the second anniversary of her confirmation to the Court.it’

One possible explanation for why political disputes dominate so much of the Court’s docket, even as the volume of ordinary legal cases diminish more and more with each passing year, is that the process for selecting justices has become far more political — and far more partisan — than it used to be.

When you consider just how much power is wielded by the Supreme Court, it’s astonishing how little thought many US presidents put into their judicial appointments. President Woodrow Wilson, for example, appointed Justice James Clark McReynolds — a lazy, tyrannical jurist that Time magazine once described as a “savagely sarcastic, incredibly reactionary Puritan anti-Semite” — in large part because the president found the future justice, who previously served as attorney general, to be so obnoxious that Wilson promoted McReynolds to get him out of the Cabinet.

Similarly, President Dwight Eisenhower complained in 1958 that appointing Justice William Brennan, a titan of American liberalism who was extraordinarily effective in moving the law to the left, was one of the two biggest mistakes he made as president (the other was appointing Chief Justice Earl Warren, another highly consequential liberal appointee). But the Eisenhower White House did very little to vet Brennan ideologically, and Eisenhower selected him in large part because Brennan was Catholic and Ike wanted to appeal to Catholic voters.

To this day, many Republican judicial operatives still use the battle cry “No More Souters” to describe their approach to Supreme Court nominees, a reference to Justice David Souter, a George H. W. Bush appointee who turned out to be a moderate liberal after he was appointed to the Court.

Since Souter’s appointment, both political parties have grown far more sophisticated at vetting potential nominees to ensure that they won’t stray from their party’s ideological views after their elevation to the bench. On the Republican side, organizations like the Federalist Society begin to vet potential nominees almost as soon as they enter law school. And it’s notable that every Republican justice except for Barrett served as a political appointee in a GOP administration, where high-level Republicans could observe their work and probe their ideological views.

The Democratic vetting operation, meanwhile, is more informal but no less successful. None of President Clinton’s, Obama’s, or Biden’s Supreme Court appointments have broken with the Democratic Party’s general approach to judging in the same way that Souter broke with Republicans.

So it shouldn’t surprise anyone that justices chosen largely because of their political ideology, rather than because of their records as neutral and impartial jurists, appear to be more interested in deciding political questions than they are in resolving legal disputes.

A version of the story appeared in Today, Explained, Vox’s flagship daily newsletter. Sign up here for future editions.