Technology

Technology  Oregon’s opioid crisis: Why the state is going to recriminalize all drugs, including psychedelics like LSD, MDMA, and ketamine

Oregon’s opioid crisis: Why the state is going to recriminalize all drugs, including psychedelics like LSD, MDMA, and ketamine March 16, 2024:

In 2020, it looked as though the war on drugs would begin to end in Oregon.

After Measure 110 was passed that year, Oregon became the first state in the US to decriminalize personal possession of all drugs that had been outlawed by the Controlled Substances Act in 1970, ranging from heroin and cocaine to LSD and psychedelic mushrooms. When it went into effect in early 2021, the move was celebrated by drug reform advocates who had long been calling for decriminalization in the wake of President Nixon’s failed war on drugs.

Now, amid a spike in public drug use and overdoses, Oregon is in the process of reeling back its progressive drug laws, with a new bill that aims to reinstate lighter criminal penalties for personal drug possession. And while the target is deadly drugs like fentanyl, the law would also result in banning non-clinical use of psychedelics like MDMA, DMT, or psilocybin — drugs that are unconnected to the current overdose epidemic and the public displays of drug use.

By treating all drugs as an undifferentiated category, Oregon is set to deliver a major blow to advocates of psychedelic use who don’t want to see expensive clinics and tightly controlled environments be the only legal point of access. While regulated and supervised models for using psychedelics are showing growing promise for treating mental illness, decriminalized use allows for a much wider spectrum of user motivations — many of which have occurred for millennia — no less deserving of legal protection, from recreational and spiritual to the simple pleasure of spicing up a museum visit with a small handful of mushrooms.

“The biggest threat to psychedelics is from people who would claim to be for them in extremely limited contexts and against them in all others,” said Jon Dennis, a lawyer at the Portland-based firm Sagebrush Law specializing in psychedelics.

It would be one thing if arguments against the decriminalization of psychedelics were being made. But that’s not the case. Instead, the lumping together of psychedelics and opioids seems to have gone largely unnoticed, setting up personal use of psychedelics to become an unintended casualty of Oregon’s opioid crisis.

The idea behind drug decriminalization was that investing in health services and harm reduction are more effective and humane responses to substance abuse than incarceration. The hope was for Oregon to serve as inspiration for other states, and eventually the nation, to follow suit.

But in the years that followed, Oregon fell deeper into an opioid and drug overdose crisis that has been surging across the nation. In 2021, the US had over 80,000 opioid-related overdose deaths. Beyond the death toll, critics — fairly or unfairly — connected decriminalization to the rising visibility of drug use and homelessness in Oregon towns and cities, including open-air fentanyl markets popping up in downtown Portland. That put increasing pressure on Oregon legislators to do something to change the state’s drug policy.

The new solution crafted by state Sen. Kate Lieber and state Rep. Jason Kropf — House Bill 4002 — is intended as a compromise between the full decriminalization of Measure 110 and the status quo before that leaned heavily on incarceration for drug possession. While improving access to substance abuse treatments — like reducing barriers to receiving medication and encouraging counties to direct offenders to treatment programs rather than court — the bill recriminalizes personal possession of all controlled substances (except for cannabis), bringing back the possibility of jail time for possession of even relatively small amounts.

Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek last week announced that she intends to sign the bill within 30 days of it clearing both state legislatures with bipartisan support. It’s been widely described as “this very precise amendment that’s only going to address the problems with Measure 110, which were thought to be opioids and meth,” said Dennis.

But the bill turns out to be much larger in scope than advertised. Instead of specifically targeting the opioids and methamphetamine that have been behind most overdose deaths, HB4002 also recriminalizes personal possession of psychedelic drugs like psilocybin mushrooms, MDMA, and LSD. Unlike the concern around opioids (including synthetic ones like fentanyl, which are responsible for the majority of overdoses) or meth, neither the public nor experts have reported significant negative effects from the decriminalization of psychedelics.

“All of the conversations around the legislature didn’t think to distinguish between these different classes of drugs,” Dennis said. “I think this was just a broad oversight on their part, rather than nuanced policy discussions.”

There are no op-eds being written about tripping hippies filling public spaces in grand displays of love and cosmic beatitude. The streets are not littered with acid blotter paper or mushroom caps. Psychonauts aren’t seeking out encounters with DMT entities in public parks. No argument for recriminalizing psychedelics has been made, and yet, they’re being swept into a recriminalization bill by the debate around opioids.

Psychedelics have uncommon but potentially serious risks of their own, including short-term encounters with intense anxiety and long-term battles with destabilizing experiences. Access to safety information and support is crucial for their use. On the whole, psychedelics are far safer than many other legally accessible substances, and the list of therapeutic, spiritual, and creative benefits seems to grow each month, from alleviating depression and addiction to combating eating disorders and helping find meaning in life. Expanding access through decriminalization (together with public education and clinical resources for those in need) could help make the most of these benefits.

Before Measure 110, possession of a controlled substance like LSD or heroin in Oregon could be charged as a Class A misdemeanor, carrying a maximum of one year in jail and fines up to $6,250.

Measure 110, which passed November 2020 with 58 percent of the vote, was intended to treat substance abuse as a public health issue, rather than a criminal one. It created a new category for possession of small amounts of controlled substances — Class E violations — that came with no jail time and a maximum of a $100 fine that could be waived if the individual chose to complete a health assessment. Effectively, it meant that getting caught with illegal drugs could, at worst, get you the equivalent of a traffic ticket.

The new bill, HB 4002, scraps the Class E category altogether. If it goes into effect on September 1, possession of small amounts of controlled substances will once again be punishable with criminal offenses, though less severe than the way things worked prior to Measure 110.

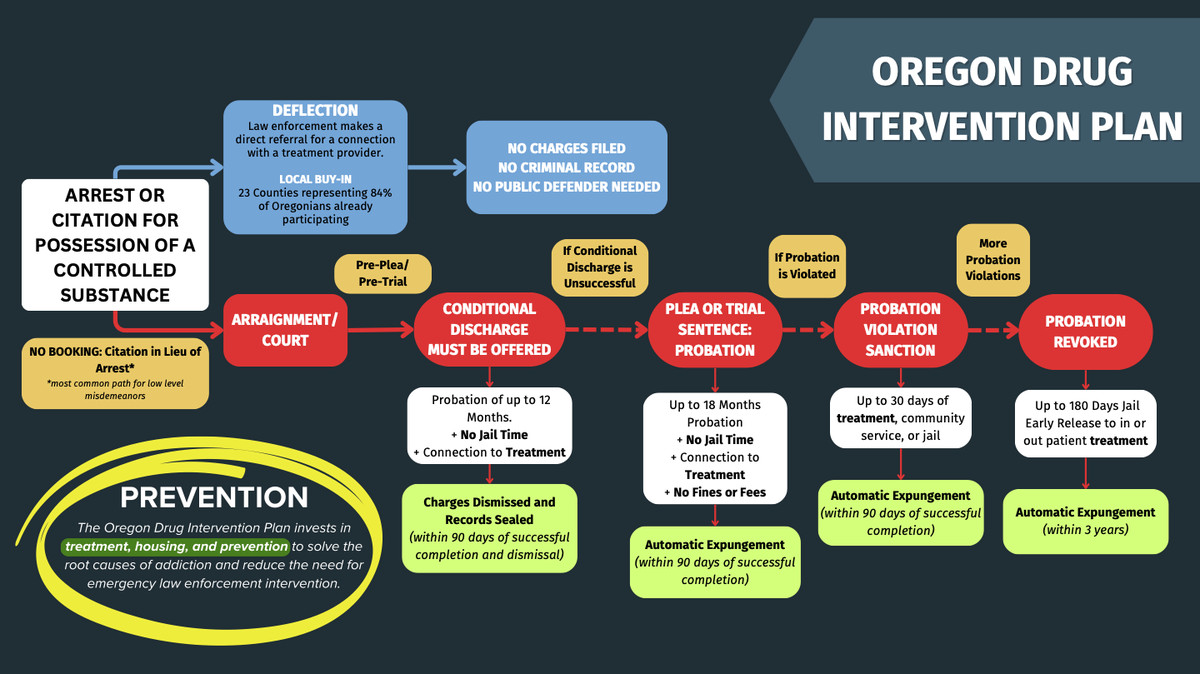

Instead of Class E violations, personal possession of controlled substances will be considered a “drug enforcement misdemeanor,” which carries a maximum of 180 days in jail, though with a series of intervening steps designed to “deflect” individuals toward treatment rather than incarceration.

Even after HB4002 goes into effect, “Oregon will be in a better position than it was prior to Measure 110,” said Kellen Russoniello, senior policy counsel at the Drug Policy Alliance. The new criminal penalties are designed to try to get people into treatment, rather than prison. “But it’s still a step backward from decriminalization.”

Sen. Lieber’s office provided me with a diagram Thursday to show all the steps meant to reduce the odds that someone charged with a drug enforcement misdemeanor will wind up in jail:

Courtesy of Sen. Kate Lieber’s office

The bill does not affect Measure 109, which implemented Oregon’s regulated access to psilocybin mushrooms. Under that model, adults can sign up for a supervised psilocybin session at a licensed facility, which can cost anywhere from about $1,000 to $3,000. Regulated ketamine clinics, where people can receive ketamine under supervision to treat conditions like depression or anxiety, are also unaffected.

But it does ensure that regulated access is the only way to legally use psychedelics, walking back the decriminalization that allowed for more affordable and unconstrained personal consumption on one’s own terms.

While decriminalization has become a focal point in the debate over drugs, Oregon’s opioid crisis was escalating before 2020. From 2019 to 2020, unintentional opioid deaths in Oregon rose by about 70 percent. After Measure 110 took effect in February 2021, the surge continued. In 2021, deaths rose another 56 percent, and another 30 percent in 2022.

Despite the trends predating decriminalization, critics felt that the rise in overdose deaths, public displays of drug use, and crime were attributable to Measure 110. That provided a strong base of support for HB-4002. An April 2023 survey of 500 Oregon voters found that 63 percent supported bringing back criminal penalties for drug possession while continuing to use cannabis tax revenue for drug treatment programs. The bill was sold as a compromise that would stem the chaos that Measure 110 had allegedly unleashed.

But during the post-decriminalization years that saw Oregon’s opioid crisis continue to worsen, the same trends were taking place across the country, including in neighboring states that hadn’t decriminalized opioids, like California and Nevada. A study led by the New York University Grossman School of Medicine and published in JAMA Psychiatry found that in Oregon and Washington, both states that had drug decriminalization policies in 2021, there was no evidence for an association between decriminalization and drug overdose rates.

A second study, led by public health researcher Brandon del Pozo of Brown University and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, replicated the findings for Oregon: no link between decriminalization and drug overdoses. Instead, most of the spike was attributed to the introduction of fentanyl into the general drug supply. Fentanyl is up to 50 times stronger than heroin, and is often laced into unregulated drugs like heroin or cocaine, making it far more likely than other drugs to lead to fatal overdoses.

Much of the public sentiment’s swing against decriminalization centers around the visibility of drug use, rather than the numerical impact on overdose deaths. So it’s worth noting that the same year that decriminalization was passed, Covid-era eviction protections also expired. After plummeting in 2020 and 2021, the eviction rate shot back up in 2022 by nearly 25 percent. Between 2022 and 2023, the state’s homeless population rose by 12 percent.

None of this is to definitively say that Oregon’s decriminalization did nothing to worsen the opioid crisis, but their less-than-ideal implementation certainly seemed to amplify the visibility and social disorder associated with it. By failing to fund programs that would have trained law enforcement (who were generally skeptical of decriminalization to begin with) on how to direct drug users toward rehabilitation or designing a ticketing system that emphasized treatment information, even advocates of Measure 110 were dismayed with the form it took through implementation.

“Certainly, there’s a sense among Oregon voters that what’s going on isn’t working,” said Russoniello. But blaming Measure 110 has been called political fearmongering, rather than evidence-based policy. “The opposition was able to take the frustration with all of these social issues that Oregonians are facing and direct people’s frustration and anger at the big red herring of Measure 110, even though it isn’t backed by any sort of evidence.”

And wherever the debate falls on what’s fueling the opioid crisis, psychedelics are another matter entirely.

There’s reasonable and urgent debate to be had over the best way to regulate opioids and support users. Advocates maintain that a well-implemented decriminalization approach is both more effective and equitable (minority groups are significantly overrepresented in Oregon’s criminal justice system) than returning to criminal penalties, even if recriminalization comes with “deflection” programs in place designed to make incarceration the sanction of last resort.

And yet, when it comes to psychedelics, the same questions, concerns, and sense of urgency present in the opioid crisis are notably absent.

The therapeutic value of psychedelics in regulated settings is well on its way to federal recognition, with the FDA expected to approve MDMA for treating PTSD as soon as this August, and psilocybin for depression to follow suit. But decriminalization can serve as a complement to the shortcomings of medicalized psychedelics, helping to mitigate concerns around access, affordability, and preserving the diversity of purposes for which psychedelics have long been used.

Critics of what has been called “psychedelic exceptionalism” argue that the law should not encode moral judgments that label some drugs as better or worse than others. The logic of decriminalization applies to all drugs, not only those that are more politically or culturally palatable. In fact, “The impact of decriminalization of heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine will be greater than for psychedelics,” said Russoniello, “because more people are incarcerated for those drugs than for psychedelics.” Even so, that shouldn’t mean that progress on decriminalizing psychedelics should get stymied by the ongoing debate over opioids.

So far, experts I spoke with who were concerned about criminalizing psychedelics despite the lack of evidence or argument for it could point to no public efforts to change the bill or clarify its effects. “I don’t think most legislators even really knew that this [HB4002] was recriminalizing all drugs,” said Dennis. HB-4002 now awaits Gov. Kotek’s signature.