March 8, 2024:

While running a microfinance company working across rural India in 2014, neuroscientist Tara Thiagarajan had a free Sunday, a portable EEG headset, and a question: What is modernization doing to our brains?

In a DIY experiment using herself and colleagues as baselines, they found striking differences in brain activity between their urban brains with lifelong exposure to modernity, and those who’ve spent their lives in small Indian villages. At the time, a criticism of studies on mental health was that they were mostly based on findings from small samples of Western college students — a poor experimental design to figure out how differential exposure to modernization and technology affects mental well-being across the world.

By 2020, she had founded a nonprofit called Sapien Labs, built a survey that reached 49,000 people across eight English-speaking countries, and published Sapien’s first Mental State of the World (MSW) report, which measures what they call the “mental health quotient,” or mental well-being score, of respondents. The findings weren’t great. Compared to responses from 2019, the 2020 mental well-being score (which notably captured the pandemic onset) dropped 8 percent. Forty-four percent of young adults reported clinical level risk, compared with only 6 percent of adults 65 and over.

Monday, Sapien released its fourth annual Mental State of the World report with data from more than 400,000 respondents in 13 languages across 71 countries. The bottom line: Our modern minds do not appear to be recovering from that drop in the early pandemic years.

The mental well-being report is part of a larger effort, the Global Mind Project, where Sapien Labs uses its survey data — which runs continuously throughout the year (you can fill out the assessment here; it takes about 15 minutes to complete) — to gauge not only the mental state of affairs but to look for causal factors.

If “modernization” is harming our minds as Thiagarajan suspects, what exactly is doing the damage? “The Global Mind Project allows for very quick understanding at a very large scale, which has not been possible before,” said Thiagarajan.

Along with their annual overview of mental well-being, the project publishes more targeted reports that home in on different possible scourges of modernity, like access to smartphones at younger and younger ages, ultra-processed foods, and the breakdown of family relationships.

“Greater wealth and economic development does not necessarily lead to greater mental wellbeing, but instead can lead to consumption patterns and a fraying of social bonds that are detrimental to our ability to thrive,” the report cautions.

A number of Our World in Data graphs show how economic growth still tracks really well with human prosperity in the long run. The evidence that economic growth tracks with goods and services that enable human prosperity is compelling, but as my colleague Sigal Samuel reports, figuring out how best to approximate human well-being is still an ongoing and lively discourse.

Thiagarajan takes a nuanced approach, arguing against a simple binary choice between growth or degrowth. Instead, she argues that what matters is how wealth is created and toward what ends it’s used. Or, as the economist Mariana Mazzucato often puts it, what matters is the “direction” of growth and whether it’s angled at the common good.

“At the moment, growth is causing harm,” Thiagarajan said. “But there are different types of growth.”

There is, as of yet, no exact science of mental well-being, let alone a perfect cross-cultural survey. “People commonly conflate things like mental well-being with happiness,” said Thiagarajan. But if you compare the findings from their mental well-being survey to the World Happiness Report (WHR), a publication by Oxford’s Wellbeing Research Centre, much of the results are inverted.

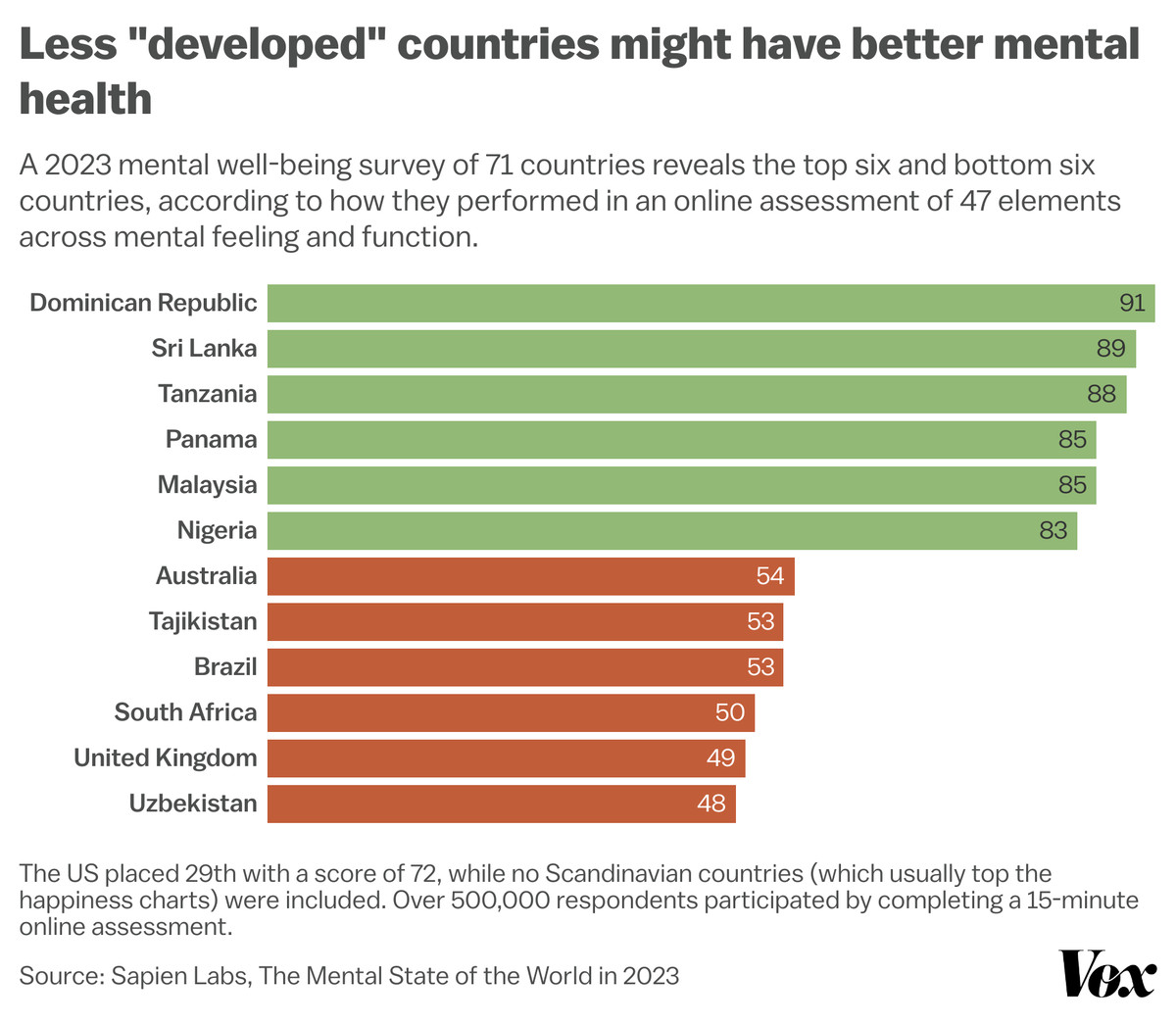

The Dominican Republic and Sri Lanka have the highest average mental well-being scores on the Mental State of the World list. On the World Happiness Report, they rank 73rd and 112th, respectively. Tanzania is third on the MSW and 128th on the WRH. What’s going on?

The World Happiness Report leans on capturing what Thiagarajan described as “feeling.” That includes respondents rating their life satisfaction on a scale from one to 10 and daily measures of whether they felt laughter, enjoyment, or interest the day before. But you could feel great and still be functioning poorly in the world. Following the World Health Organization’s definition of mental health, which includes the capacity to function productively and contribute to society, Thiagarajan wanted the Global Mind Project to capture functioning, too.

To build their measure, the mental health quotient, Thiagarajan and her team found 126 different kinds of assessments used across academia and clinical environments, and then boiled those down to 47 aspects of mental health. Then, rather than asking about frequency, like “How many times did you feel sad yesterday,” the MHQ sets its questions along a life impact scale, based on the idea that it’s easier to report how impactful something is to your life than how many times you drank water or laughed the day before (I couldn’t tell you either of those for yesterday).

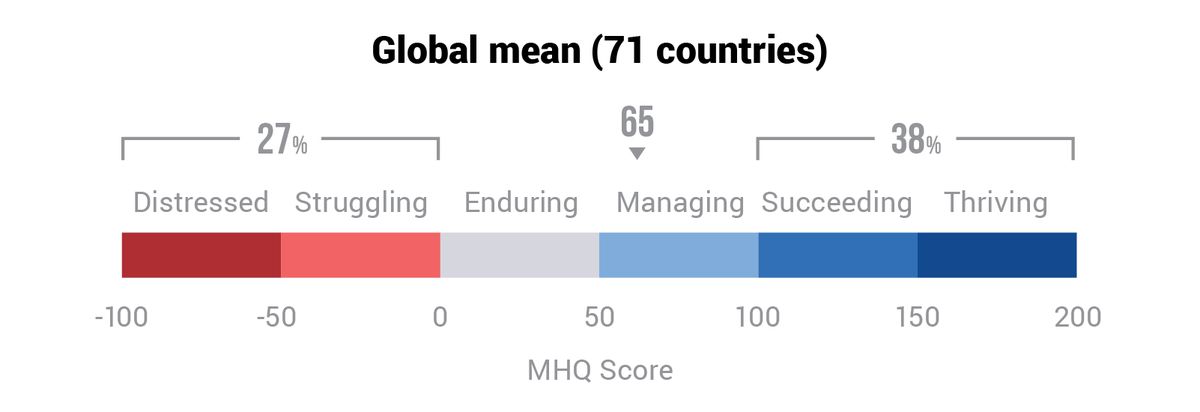

Their results produce a number along a 300-point scale that ranges from “distressed” at the low end to “thriving” at the high end.

For 2023, across the 71 countries they received data from, the global average was 65, indicating that we’re all “managing,” and doing so just a few hairs above “enduring.”

There’s a theory going around that, as former neuroscientist and author Erik Hoel put it, the modern world was invented in 2012. For social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, 2012 also marks the beginning of the teen mental illness epidemic.

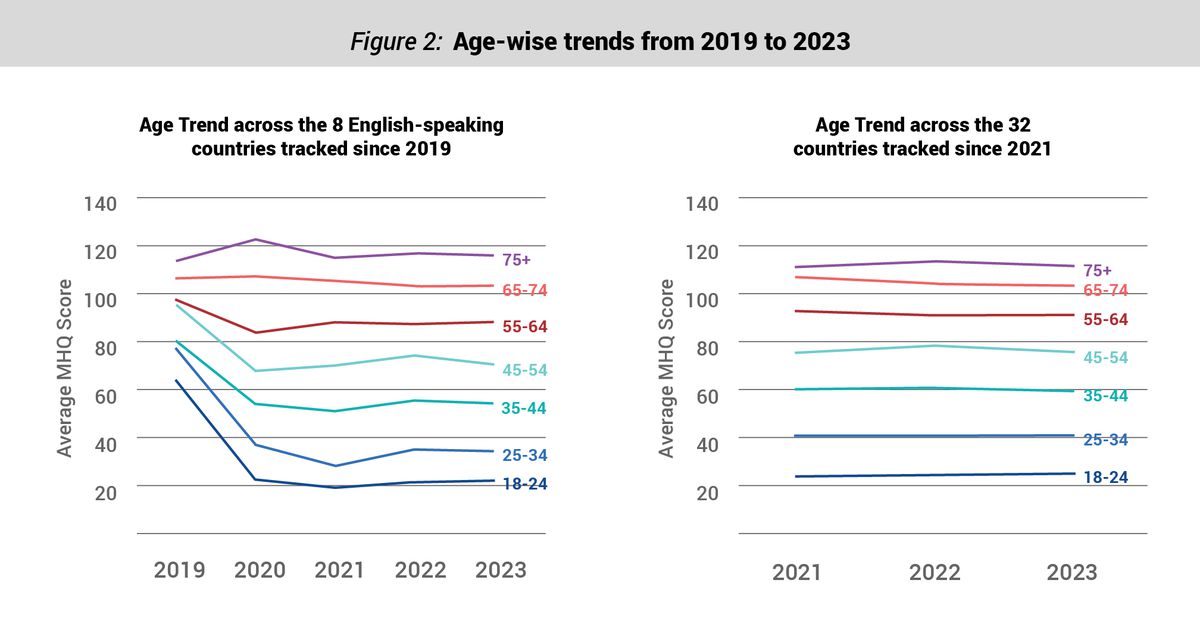

Findings across the four years of the MHQ agree. Prior to 2010, young people tended to top surveys of happiness, mood, and outlook. But from 2019 until this year’s report, the most persistent trend observed has been declining mental well-being across the “internet-enabled” youth (because the survey requires internet access) of every country measured, from Africa to Asia, Europe to the Americas.

The youth, once the peak of reported happiness, have dropped to the absolute bottom, while others, like those 65 or older, have remained basically the same.

To be more precise: For the eight English-speaking countries with data collected since 2019, those aged 18–24 and 25–34 dropped by 14–17 percent. That decline gradually flattens out as you move up the age brackets.

Global Mind Project / 4th Annual Mental State of the World Report.

According to the Global Mind Project’s report on smartphone use in May, the smartphone hypothesis — which has been advocated for by psychologists like Jean Twenge — holds up. “The younger you get your smartphone, the worse off you are as an adult,” said Thiagarajan.

The more you break down the demographics, the more you find that the consequences of smartphone use are concentrated on young females. But looking at another potential causal factor they recently published on, the consumption of ultra-processed foods, those effects are universal across all demographics. “It affects everything, every aspect of mental functioning,” said Thiagarajan.

Their report notes the complexities involved in defining ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and provides a simple rule of thumb: food with substances you would rarely find in a home kitchen (it’s worth noting that the entire category of UPFs is still under scrutiny, particularly for targeting plant-based foods). Even after trying to control for the indirect effects of exercise frequency or income, they found that those who eat UPFs several times a day have a threefold increased risk for serious mental health issues.

There are plenty of other possible confounding variables, like frequency of cooking or sharing meals, but their findings are large: “We’re looking at when you rule out all the other 100 things that we can capture data on,” Thiagarajan said, “and ultra-processed foods seem to account for at least a third of the global burden of mental health that we see.”

The last culprit she singled out was family relationships. And yes, there’s a report for that too, which finds the breakdown of family relationships across the modern world as a major factor in the decline of youth mental well-being. Families with less exposure to the institutions and technologies of modernity, the report argues, tend to have stronger and more numerous family bonds, which tracks closely with better mental well-being.

Thiagarajan explained how when they got their first MHQ results, they wondered why countries like Venezuela and Tanzania came out on top. “But it’s these factors,” she said. “They can’t afford all the westernized ultra-processed foods so they don’t import them. They don’t give smartphones to their kids so young. And they have large families that stay together.”

She noted that given the speed and scale of “the issue” — that issue being, well, modernity — we’re forced to take action on imperfect knowledge. Part of the goal of the Global Mind Project, across the MHQ and its more targeted reports, is to help figure out the most effective places to aim policy efforts, particularly regulations.

“If it’s a free-for-all,” she said, “people will take the easiest shortcut to short-term profits at the expense of mental health.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here!