Technology

Technology  How big are factory farms? How mega-sized factory farms took over America’s food system, explained in 9 charts.

How big are factory farms? How mega-sized factory farms took over America’s food system, explained in 9 charts. February 26, 2024:

In a few generations, factory farming — the set of economic, genetic, chemical, and pharmaceutical innovations that enabled humanity to raise tens of billions of animals for food every year — has transformed America.

It has polluted our water and air, ruining quality of life for people who live near animal confinements. It has altered entire landscapes, helping drive the conversion of much of the Midwest’s biodiverse prairie grasslands to soy and cornfields growing feed for billions of animals warehoused in industrial sheds. It contributes an outsized share of planet-warming emissions, heightens the risk of another zoonotic pandemic, and causes unfathomable, normalized suffering for the animals themselves.

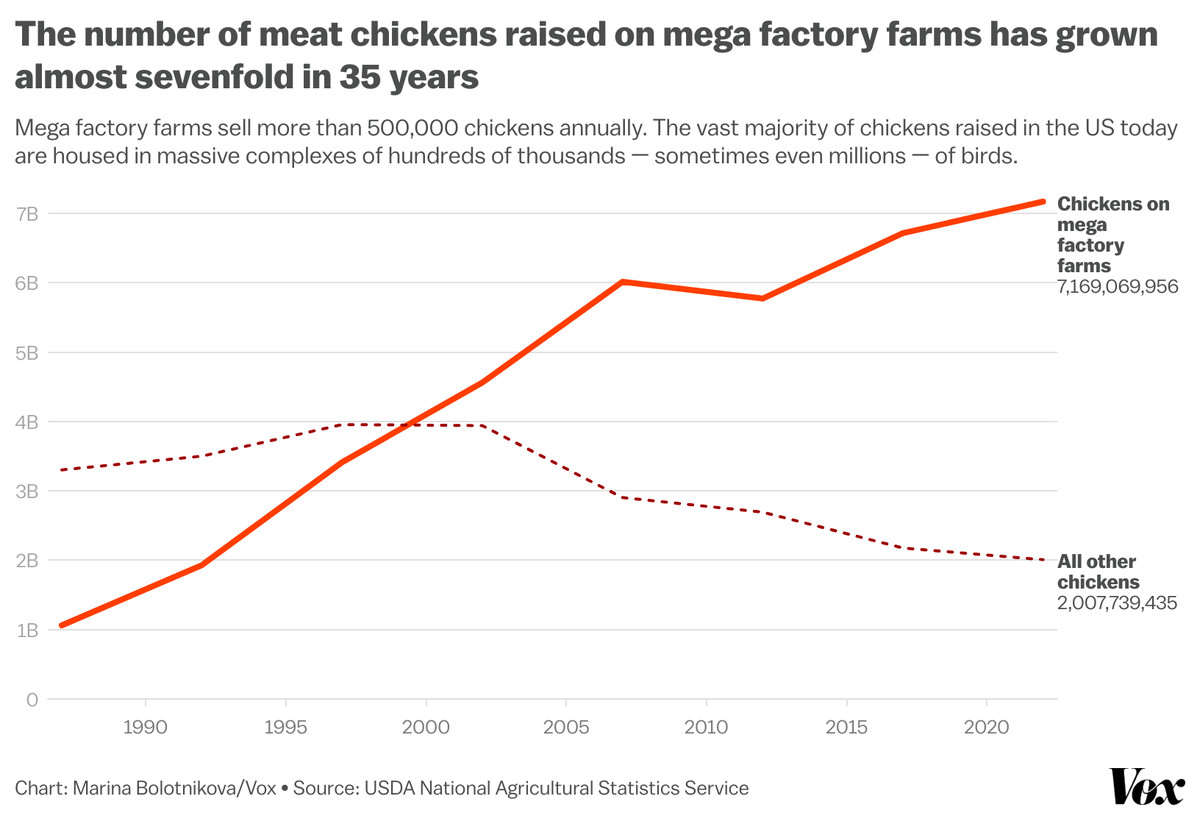

The factory farmification of the American food system dates back about a century and accelerated post-World War II. But today’s factory farms have taken on an even more extreme dimension. Forty years ago, a facility raising 100,000 chickens per year would have passed for a large factory farm; now more than three-quarters of chickens live on massive complexes that sell more than 500,000 animals annually. These mega factory farms, as some observers have called them, look more like chicken megalopolises. The same pattern holds for other animals raised for food, like cows and pigs.

These trends are reflected in data released this month by the US Department of Agriculture’s Census of Agriculture, a massive report published every five years on the state of farming in America. The report reveals a picture of an ever-consolidating, ever-intensifying system of animal agriculture that’s squeezing out small and medium-sized farms and packing more animals on less land.

Here are some of our top takeaways.

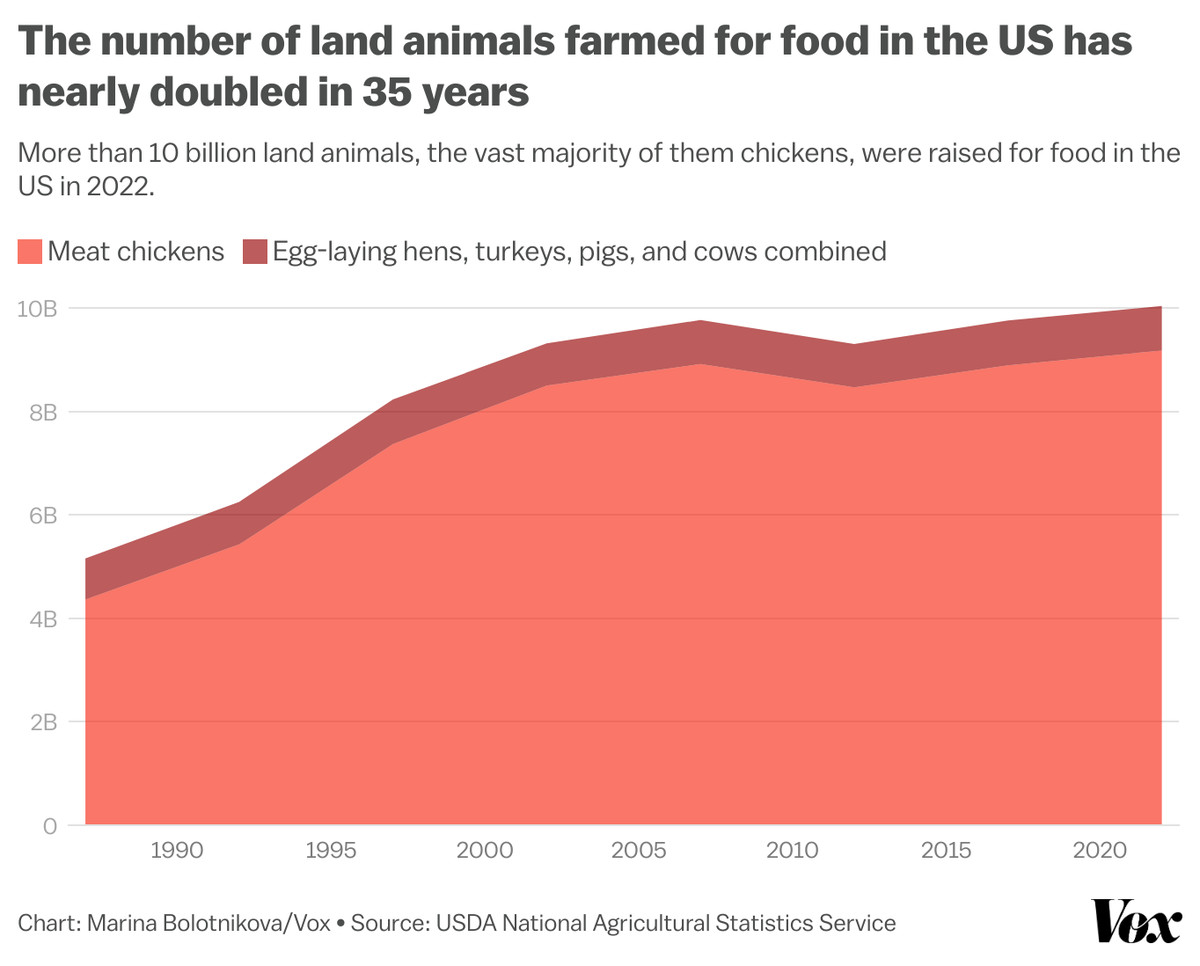

In 2022, the most recent year for which data was available, the number of chickens, cows, pigs, and turkeys in the US food system exceeded 10 billion for the first time in the census’s history — up from 5.2 billion animals in 1987.

That’s largely been driven by the chickenization of the American diet. One of the most important shifts in the US food system over the last several decades has been declining beef consumption and rapidly increasing consumption of chicken, often perceived as healthier than red meat. The ethical implications of that trade are profound. As Vox has written many times, swapping beef for chicken means slaughtering many more individual animals because chickens are small, so it takes about 100 of them to get the same amount of meat as from one cow.

US chicken meat consumption first surpassed beef consumption in the mid-1990s; around the same time, farm animal population growth accelerated, as seen in the chart above.

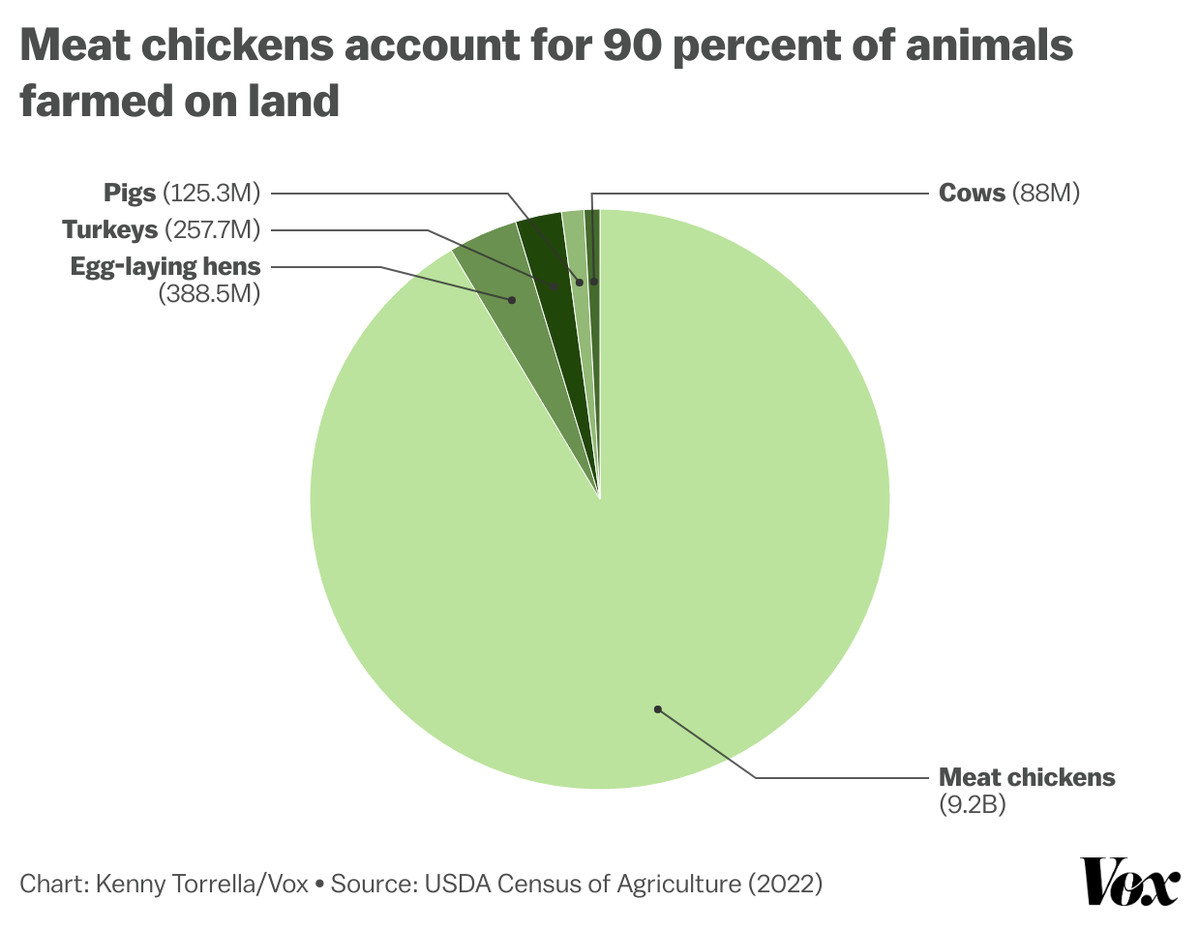

Chickens now make up more than 90 percent of land animals farmed in the US. In 2022, we slaughtered 9.2 billion of them, about 27 for every person in the country. We farm so many chickens for food that they’re now the most populous bird species in the world, and scientists believe their remains may leave a permanent mark on our geological record. “We live in the Age of the Chicken,” as the New York Times put it in 2018.

The numbers of other farmed animals are also massive, but next to meat chickens, they look like a rounding error.

With every passing year, farmed animals are increasingly concentrated on the largest factory farms.

In the chicken meat industry, mega factory farms that each raise more than 500,000 chickens per year now overwhelmingly dominate. In 2022, 7.2 billion chickens — the vast majority of chickens raised for meat in the US — came from one of these facilities. (The other 2 billion still overwhelmingly came from factory farms — just smaller ones.)

In the egg industry, which uses about 388.5 million hens per year, the biggest factory farms are even bigger, sometimes housing millions of animals in one place.

Such high concentrations of animals — and their waste — smell terrible and release hazardous air pollution linked to respiratory problems in the communities in which they’re located, a growing environmental justice issue.

These facilities have also exacerbated US avian flu crises over the last decade: Having so many animals in one place means that when a case of bird flu hits one animal, it can quickly spread to hundreds of thousands of others (which also creates more opportunities for the disease to mutate into something potentially dangerous to humans). For disease control purposes, the USDA requires farms to kill every animal on a farm where a case of bird flu has been detected, setting off a chain of events that can disrupt the food supply chain and inflate egg prices. In the span of one month in spring 2022, for example, bird flu cases at just five massive egg factory farms in Iowa, Wisconsin, and Nebraska wiped out more than 4 percent of the country’s egg-laying hens.

And because it’s logistically difficult to cull so many animals in a massive complex, these mega factory farms have also been linked to the rise of an especially disturbing method being used to mass kill animals in the bird flu: ventilation shutdown, in which birds are killed via heatstroke using industrial heaters.

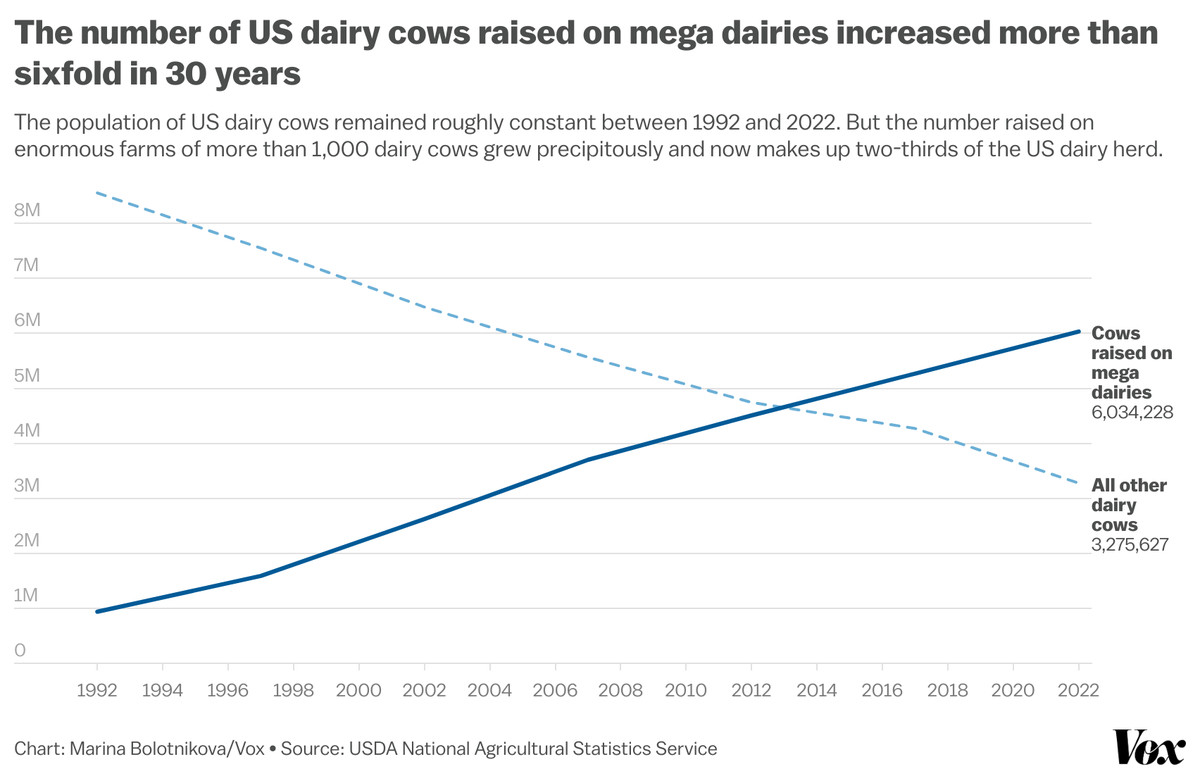

Cows are enormous, so the threshold for the largest cattle farms is much lower than it is for chickens. Remember the massive fire at an 18,000-cow Texas dairy farm last April? That’s what we would call a mega dairy — and they’ve taken over the dairy industry. Although the overall population of US dairy cows is not increasing, the number of cows concentrated on the biggest dairy farms has skyrocketed over the last 30 years, as smaller operations shut down.

The Texas dairy explosion last spring was a perfect illustration of the hazards of mega farms. It stemmed from a malfunction with the farm’s manure management equipment, instantly setting ablaze thousands of animals. Supersized factory farms create supersized disasters.

Mega dairies have been especially on the rise in the American West, Amanda Starbuck, research director for environmental advocacy group Food & Water Watch, told Vox. The group’s analysis of agricultural census data found a 60 percent increase in the number of cows in mega dairies in Oregon between 2002 and 2022. Although the state is not known for dairy production, it has seen a proliferation of especially large dairy farms in recent years, and local residents have complained about the industry’s pollution of their water supply. “Oregon has potentially the largest mega dairies in the world,” Starbuck said.

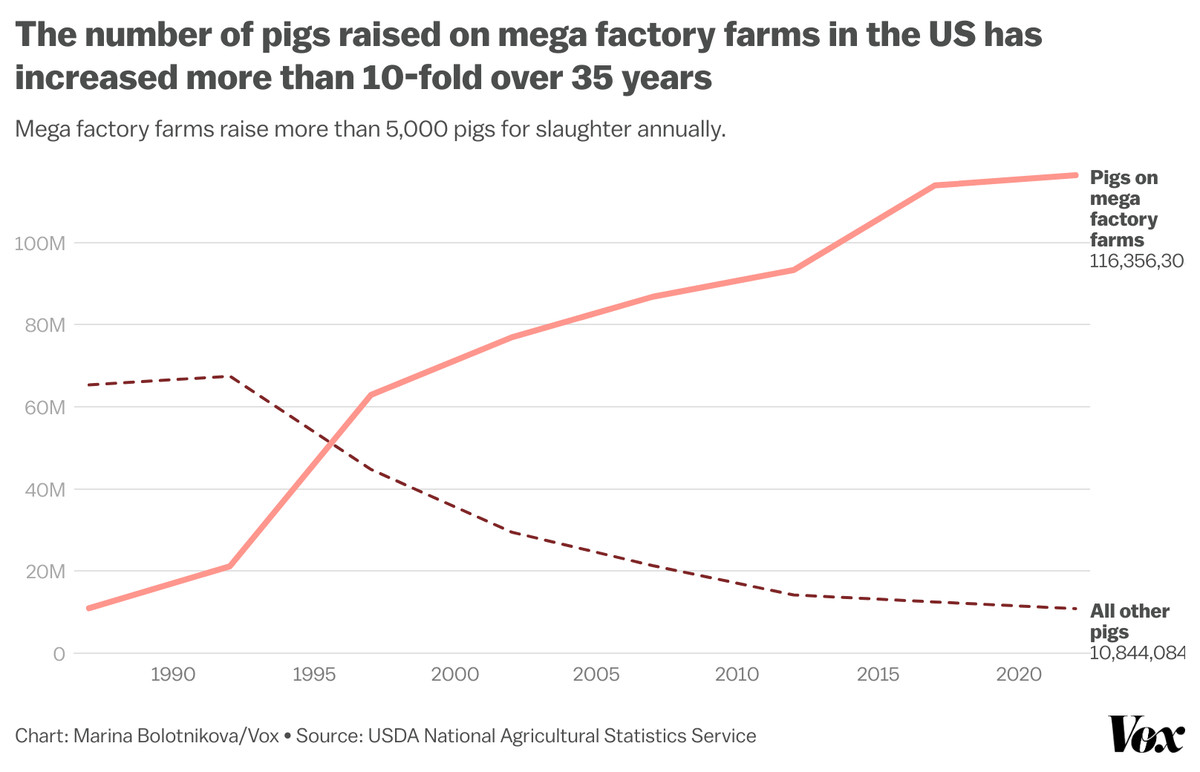

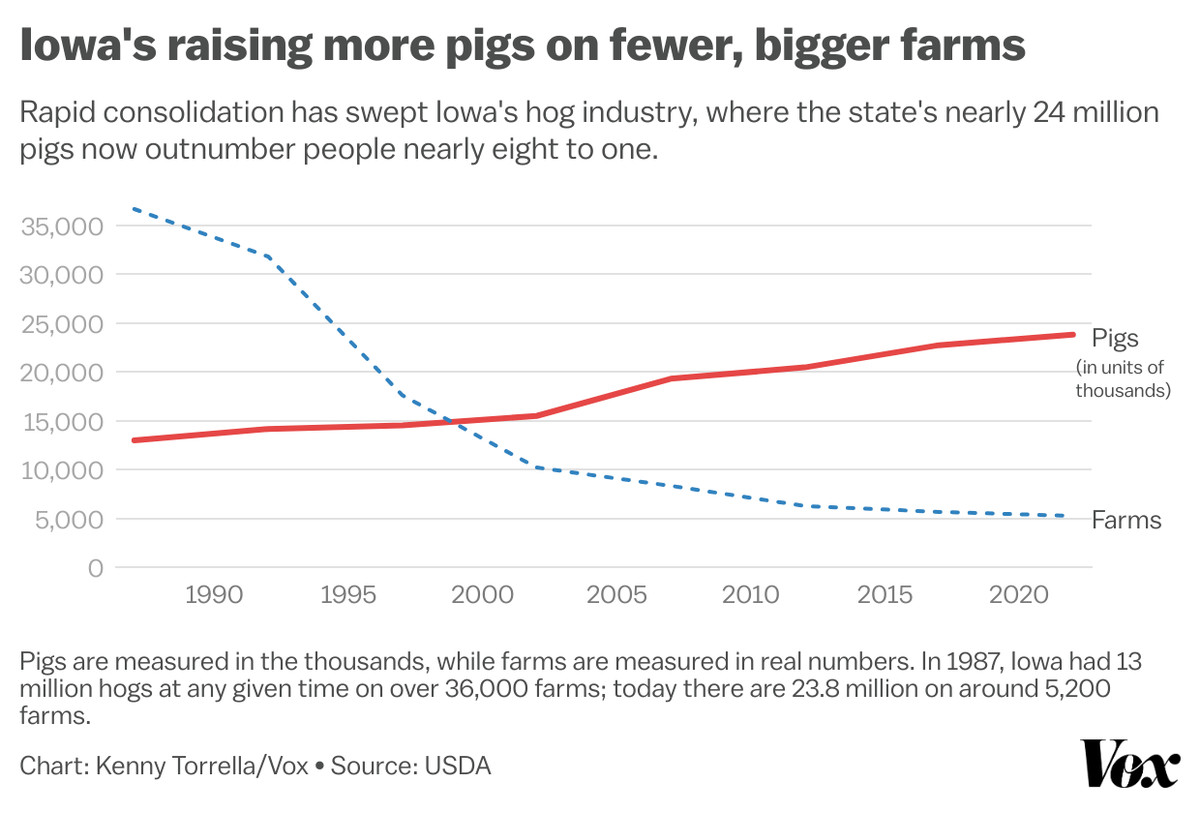

The shift to mega factory farms has perhaps been even more dramatic in the pork sector. In 2022, more than 90 percent of pigs were raised on mega factory farms.

Iowa, the top pork-producing state, has 30,000 fewer pig farms than it did in the late 1980s, yet it’s home to more pigs than ever. The rapid consolidation has meant that big farms are getting bigger while the rest go out of business, a trend consistent across the country.

Many US pig farmers who can hang on do so by contracting with the biggest pork processors, like Smithfield Foods and JBS. In these contract arrangements, the farmer takes on much of the risk by taking out large loans to build the operations, while the company supplies the pigs and their feed. More than two-thirds of pigs were raised on contract in 2015.

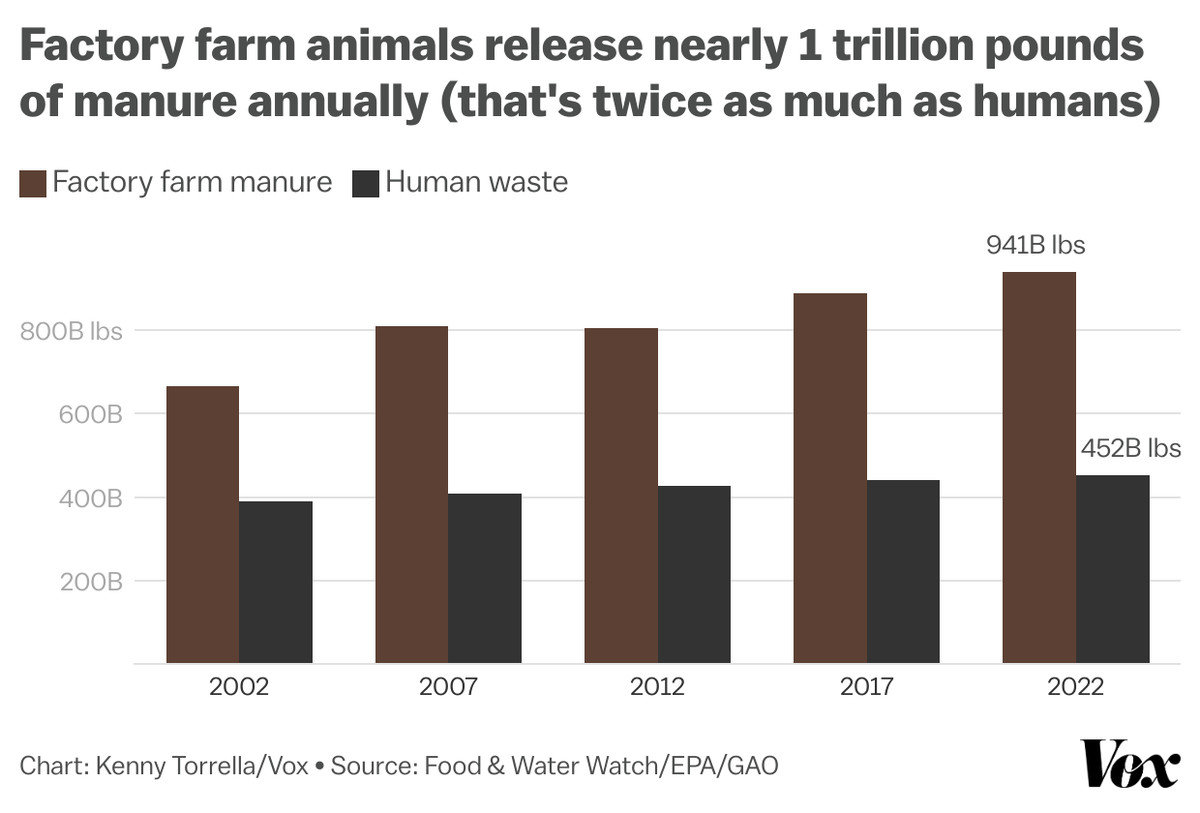

As the number of animals farmed for food has exploded, so has their waste, adding up to almost 1 trillion pounds of it each year, according to an analysis by Food & Water Watch.

Between 2017 and 2022, growth in the livestock population has added manure “equivalent to two New York City metro areas — or 40 million people,” Starbuck said.

The manure isn’t treated at sewage plants like human waste, but rather stored on the farm in piles or vast pits that are prone to leakage. Farmers also over-apply manure on crop fields to dispose of it and much of it washes away during storms into rivers and streams, causing widespread pollution.

In Iowa, more than half of the state’s rivers are “impaired,” meaning they’re not suitable for at least one of their main purposes, like serving as a habitat for aquatic animals, drinking, or recreation. Animal agriculture is the main culprit, and many rural Americans who depend on wells for drinking water have found them contaminated with factory farm waste. It’s a national problem too: A recent US Environmental Protection Agency report found that a third of US river miles were considered to be in poor shape for fish, mainly due to farm runoff.

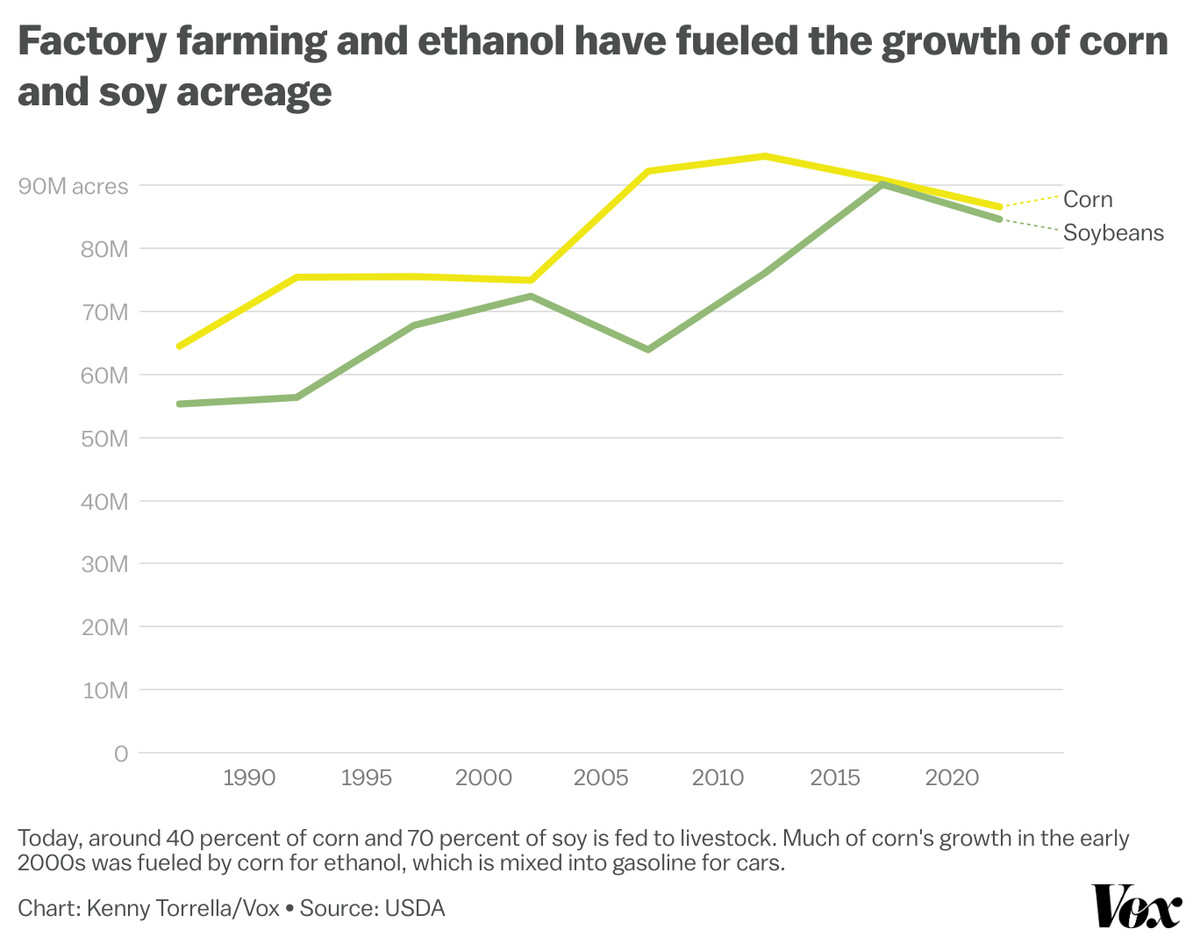

Midwest farmland and its valuable fertile soil have increasingly become devoted to growing food for farmed animals, primarily corn and soy. Like manure, much of the fertilizer and pesticide sprayed on these crops washes away during storms and pollutes waterways.

Livestock feed isn’t the only reason the US grows so much corn. There was a big spike in corn acreage starting in the early 2000s, when Congress mandated that billions of gallons of gasoline for cars be mixed with biofuels, which is mostly ethanol made with corn.

It was a terrible policy because corn is an inefficient use of land to produce energy: “It takes about 100 acres worth of biofuels to generate as much energy as a single acre of solar panels,” wrote agriculture and environmental writer Michael Grunwald in the New York Times. But it’s been hard to roll back, given the political power of the farm lobby: Ethanol policy is “mainly a way to suck up to farmers and enrich agribusinesses,” Grunwald wrote.

Almost 40 percent of US corn goes into gas tanks and 40 percent is fed to livestock, while 70 percent of soy is livestock feed.

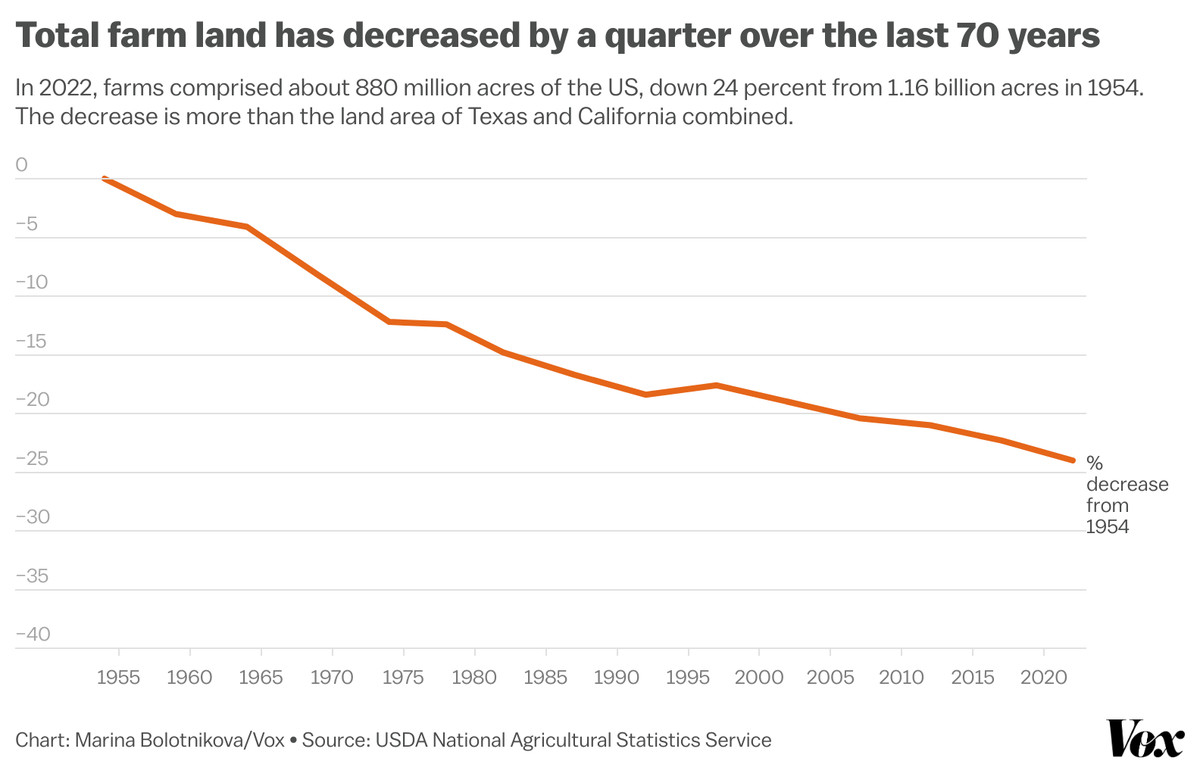

It bears mentioning that industrialized agriculture is not bad per se (at least, it doesn’t have to be). Researchers and corporations have devised ways to make crops and animals grow bigger and faster, allowing us to get more food from less land. Total US farmland has declined by 24 percent since 1954 — equivalent to saving more than the combined land area of California and Texas.

Making factory farming more land-efficient, though, has come with terrible costs not factored into the price tag at the supermarket: mass animal cruelty, pollution, and economic inequality.

Even on its own terms, factory farming is still radically inefficient compared to a system with far fewer animals and more plant-based foods, which would require less land and water, emit less pollution and climate-warming gases, and allow the country to free up land for wild ecosystems that benefit the climate.

If we’re willing to imagine a different world, one not dependent on slaughtering billions of animals for food, such a system is within reach. “The factory farm system is not inevitable,” Starbuck said.